I have been a reporter for 34 years and this was the hardest story I have ever written.

It was hard because people didn’t want to talk to me. They didn’t want to give me “fodder for woman-blaming.”

That statement, or a version of that statement (“I don’t want to pile on,” “I don’t want to blame or shame”) was the response I heard, over and over, as I tried to set up interviews for my story about the dramatic rise in the percentage and number of Maine children born to single mothers — and the consequences of that rise.

The objections and hesitations came mostly from people who work with these parents or their children: teachers, school administrators, social workers, agency or advocacy group staff, doctors and nurses. There were legitimate reasons they didn’t want to speak — they didn’t want to cast aspersions on the very people they are trying to help, or confidentiality laws limited how much they could say.

But some wouldn’t talk because they took offense at my questions about why people were having babies they couldn’t afford to care for. Off the record, they’d admit that they were frustrated when they saw poor single mothers have a second or third baby with a different dad who was, like the previous ones, unlikely to stick around. But they wouldn’t say such things on the record.

And some of the people I wanted to interview didn’t want to talk for a political reason. They said that Maine’s government under Governor Paul LePage was waging “a war on the poor,” and they didn’t want to give ammunition to that effort.

So a lot of these people wouldn’t talk to me. Or they talked to me — and then called me a day or two later and said, nervously, “Please don’t quote me.” Or they asked to see the story before it was published so they could approve their quotes. (We don’t do that.) Still others never answered my phone calls. Or made appointments for interviews and then cancelled at the last minute.

As soon as I went outside of Maine, the many policy experts, scholars and advocates who are studying this issue on a national level would talk without fear. And between my many months of research and these interviews, I knew that there was a big problem in Maine — and a big story that wasn’t being told. The reluctance of people to talk about it just made me more determined to tell the story.

It wasn’t just educators, advocates and policymakers who wouldn’t talk to me.

It was single mothers, too.

Many single mothers flat-out refused to talk. Others made appointments and then failed to arrive at the appointed hour. I drove from Hallowell to Machias — more than 300 miles roundtrip — to interview a mother who never showed up. I understood their reluctance: We are not far from a time when the women we now refer to as “single mothers” were called “unwed mothers.”

And then there were the mostly absent fathers of these families who were nowhere to be found — until I found a large population of them in the Maine State Prison. The prison runs classes designed to help fathers learn to handle their emotions better and take on the full responsibilities of parenthood once they’re released. In those classes, the fathers talked.

I am immensely grateful to those people who did talk to me, to the teachers and administrators and social workers and, yes, mothers who spoke candidly about this big, and largely unacknowledged, problem in Maine. The information they gave me and the observations they made were crucial to telling this story — which is a story that needs to be told if Maine is to help its children have the full and productive lives they deserve. As Pastor Susie Maxwell of Machias’ Old South Congregational Church said to me, “You have to be able to name it or you can’t work with it.”

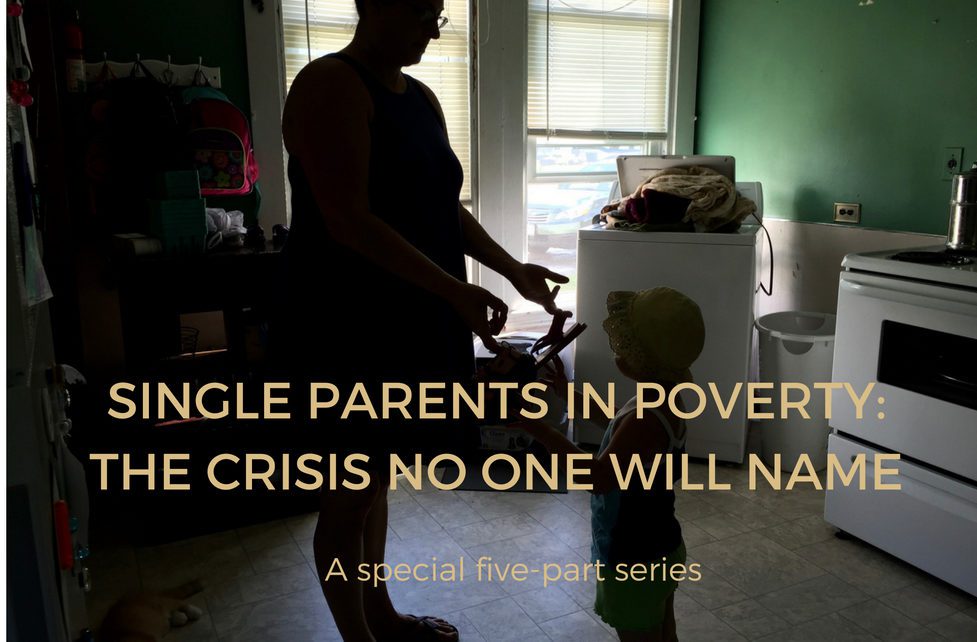

Among the people who talked to me was the clear-eyed and courageous single mother who allowed me to come to her home — interrupting the work she was doing to support her family — and ask her many questions over many days of interviews. We have not named this woman because she is a victim of domestic violence. Her stories — told with frankness and sometimes regret — helped me, and will help you, understand just what it means to be a single mother in poverty in Maine.

On my first visit, the sky darkened and a wild thunderstorm blew in just as I arrived. As we settled down to talk in a room upstairs, her daughter played with a teenaged babysitter down below. A huge gust of wind hit a tree in the neighbor’s yard and a heavy limb cracked off, taking with it the local power line and shaking the house. The lights went out.

The mother got up and looked out the window at the downed limb and power line, and then turned back to the darkened room.

“This is what it’s like for me every day,” she said.

Over a period of nine months, Senior Reporter Naomi Schalit researched and wrote a five-part series, “Single Parents in Poverty: The Crisis No One Will Name.” To read the full series, click here.