While the state is considering cutting aid to schools and communities, it is also spending more than $100 million a year on tax breaks for businesses that an audit has criticized as risky investments.

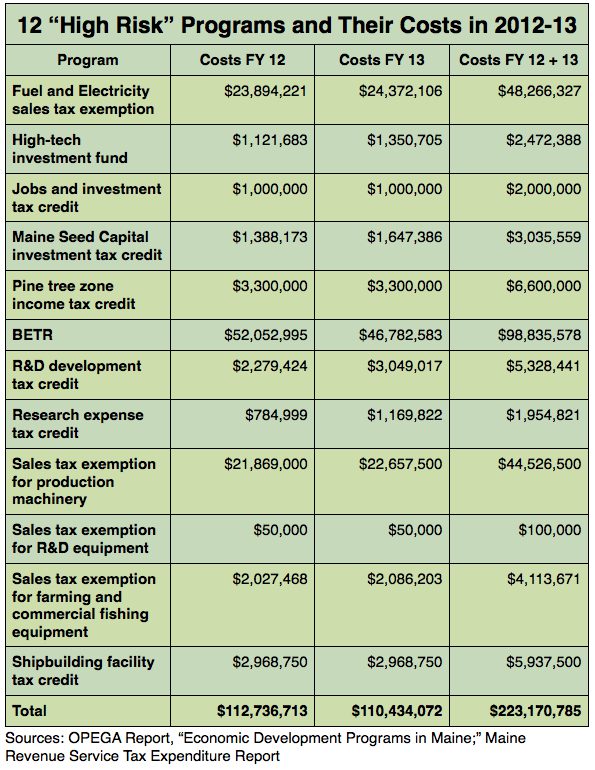

According to the audit, 12 programs that reduce taxes on hundreds of businesses lacked the “ability to evaluate … performance and provide accountability.”

The state Office of Program Evaluation and Government Accountability (OPEGA) studied a total of 46 business incentives designed to promote job growth and designated a dozen as “high risk.” Among the problems found were inadequate performance measures, costly duplications and the lack of independent reviews that could cause “mismanagement and fraud to go undetected.”

The legislature has had the report for six years, but no significant changes have been made in any of the programs, based on a review of legislation during that period.

On the contrary, just two years ago, the lawmakers created a new business tax credit that in its first year will cost taxpayers more than $5 million, according to the Maine Revenue Service.

Reducing or eliminating what critics call corporate welfare has proved difficult because of the political clout of businesses, the lack of actionable data and plain inertia, say experts and legislators.

“It’s just very powerful, the lobby for the business community,” said former three-term state Sen. Ethan Strimling, D-Portland. “They would come in front of you and say ‘If you create this tax break, we will create 300 jobs.’ I’d say, ‘Ok, we’ll put that in the contract language.’ They’d say, ‘Oh no.’”

While the two-year budget submitted in January by Gov. Paul LePage includes such cuts as $400 million from aid to cities, towns and school districts, only one minor change is proposed to reduce the cost of the state’s multitude of tax breaks, loopholes and incentive programs for business.

That proposal would reduce the cost of the $55 million business equipment tax break (BETR) by $2 million and suspend the program for one year. But it also shifts part of the cost of the programs to cities and towns. BETR is one of the dozen programs criticized by OPEGA.

LePage’s budget chief Sawin Millett, commissioner of the department of administration and finance, was unavailable for an interview or to reply to emailed questions despite numerous requests over more than a week.

OPEGA’s audit said “high risk” programs have an “increased likelihood” of being ineffective, unnecessary, spending too much on administrative costs and overspending in some areas while under-spending in others.

Among the risky tax breaks is one that gives businesses back 95 percent of their sales tax for fuel and electricity. It costs the state treasury nearly $25 million every year. OPEGA said that the tax break failed in 10 of the 13 “control criteria” it measured.

Other programs that rated poorly ranged from the $3.3 million spent annually for tax credits to businesses in Pine Tree enterprise zones to one exempting businesses from paying a sales tax on manufacturing equipment at an annual cost of $22 million.

UPDATE, Feb. 25: After publishing this story on Feb. 20, MCPIR finally received a response via email.

“Quite simply, three Committees of the Legislature reviewed the OPEGA report over the 2007-2008 biennium and took no action to modify or eliminate those programs — with the single exception you have referenced — thus those programs have remained in statute,” Millett responded to the question of why Gov. LePage is continuing the programs despite the OPEGA ratings. “It is my personal expectation, however, that there will likely be specific proposals advanced, and considerable discussion had, during the current Session as to whether all such programs should remain intact, going forward.

$602 million in three years

And the 12 riskiest programs do not tell the full picture of the incentives.

All 46 programs together cost $602 million from 2003 to 2005, according to OPEGA. There has been no official estimate since then, but all of the programs are still in effect.

Whether the incentive programs have the intended effect – job creation – is a matter of skepticism among experts.

In 2009, the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston convened a panel of experts to debate state business incentives.

Peter Enrich of Northeastern University concluded that the scholarship on the issue should lead government to “Just say no” because there is no assurance the programs create jobs.

A 2012 report by the Maine Center for Public Interest Reporting about the Pine Tree Zones program, which has cost the state $46 million since 2003, found the state has no documented proof the program created jobs as promised.

The legislature in 2009 was so concerned about the costs of the Pine Tree program that it asked a commission of economists and business leaders to find out if the program would deliver on its promise to create jobs in return for favorable tax treatment.

But the commission begged off the assignment, concluding that a lack of verifiable data meant it was “unable to develop a credible separate forecast.”

In its investigative report last year called, “United States of Subsidies,” the New York Times came to a similar conclusion:

State agencies don’t know “if the money was worth it because they rarely track how many jobs are created. Even where officials do track incentives, they acknowledge that it is impossible to know whether the jobs would have been created without the aid.”

The Times tallied the annual cost of the incentives at $80 billion nationally and Maine’s at $504 million – which equals about one-sixth of the state’s annual budget. And twice what the state spends each year on higher education.

The Times said the business tax breaks cost every Mainer $379 per year.

An op-ed column in the business-oriented Wall Street Journal on Feb. 9 by a former Republican candidate for governor in Connecticut called incentive programs “problematic.”

“If many job incentives are poor public investments, why do states get away with offering them?,” wrote co-author Tom Foley. “Because good policy and good politics are often at odds. Politicians want to be re-elected, and a solid record on nominal job growth—regardless of the cost—tends to be more important to officials’ re-election prospects than is the prudent management of public funds.”

Legislators thwarted

The problems with business tax breaks have not gone unnoticed in the legislature – there have been discussions for at least 10 years about whether they are worth the expense to the state’s budget, especially when other parts of the state budget are being cut.

But legislators say they have been stymied by two obstacles: the influence of big business and the lack of actionable data to determine which programs work and which don’t.

Former Sen. Strimling, who was on the taxation committee, said he tried repeatedly to bring up business tax breaks.

“One year, there were going to be cuts to kids with brain injuries,” he said. “A couple of us on the committee decided to make a recommendation to the appropriations committee to eliminate sales tax exemptions on advertising,” he recalled, to offset the cuts.

“Within three days, I had received 25 calls from people who were in the publication or TV industry just up in arms” and the idea died, he said.

Sen. Roger Katz, the assistant Republican leader, is a former member of the appropriations committee. He said dealing with business tax breaks, credits and reimbursements “takes a great deal of political will because, almost by definition, these exemptions are enjoyed by groups and institutions that have successfully had a voice in the legislature, and it’s hard to undo a benefit program, whether it’s a Mainecare entitlement or a tax credit.”

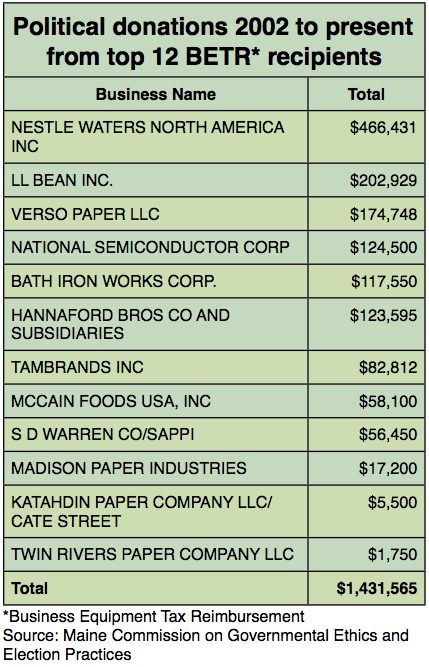

The potential influence of businesses that receive such breaks can be measured by their campaign contributions.

For example, since 2002, the top dozen businesses in the BETR tax reimbursement program have given more than $1.3 million to candidates for the legislature and governor and to political action committees.

Nestle Waters of North America , which bottles water in Maine under the brand Poland Spring, was a leading recipient of BETR in 2009, the most recent year available: $1.9 million. The company and its top executives made campaign contributions of $466,431 in the past 10 years.

Nestle has not responded to requests for an interview.

Jonathan Block, an attorney with Pierce Atwood, advises businesses on the state economic development programs. He said any assessment of the programs should make a distinction between programs such as BETR and other programs that directly promise job growth.

BETR, he said, was created by former Gov. Angus King to “level the playing field” in Maine because other states and countries didn’t penalize businesses for buying new equipment.

Unlike some of the other programs whose participants get benefits based on a “promise” of results – such as new jobs — Block said BETR participants only get personal property tax reimbursements if they actually bought the equipment.

The ‘secret budget’

The growing critique of business tax breaks has prompted legislative attention in the current session.

Like others in the legislature, Rep. Adam Goode, D-Bangor, a member of the taxation committee, said there isn’t enough transparency or accountability built into the tax breaks.

He called the millions in tax breaks “a separate, almost secret budget” that goes unexamined, while the official budget is gone over thoroughly and openly by the appropriations committee.

“It’s a weird, back door way of doing policy without having the funding become part of the state budget,” he said. “A loose end that hasn’t gotten addressed.”

Democratic legislators plan to introduce legislation to assess the effectiveness of some of the programs.

Sen. Emily Cain, of Orono, wants state budget documents to include both the financial impact and a justification for each program.

Cain said growing public interest in this issue means “the time is ripe” for a deeper examination.

But, so far, every attempt has been thwarted by a lack of data that compares what the programs intend to accomplish and what has been accomplished, she said.

“Some of these programs have been around as long as I’ve been alive,” she said. “And I’m 32-years-old.”

Veteran appropriations committee member Rep. Peggy Rotundo, of Lewiston, said her bill will ensure that any future programs to benefit businesses include “built-in transparency and accountability.”

“We need to get a sense whether or not these programs are working and worth the money we’re spending on them,” Rotundo said. “We know there’s an enormous amount of money tied up in them, buy we don’t have a good evaluation.”

Meanwhile, a state agency that administers some, but not all, of the tax break programs plans to evaluate its programs such as Pine Tree zones. The first review won’t be ready until a year from now.

None of the bills would lead to a change in the pending state budget because that budget must be approved before any of the evaluations are completed.

Geoff Herman, the longtime lobbyist for the Maine Municipal Association, said one problem with making changes is that some businesses have made investments based on promised support from the state.

Still, he said, some of the programs have been sweetened over the years, such as legislation in 2006 that changed the length of time businesses could get BETR reimbursements from 12 year to indefinitely. He attributed the change to lobbying from business.

Any changes now in business tax breaks, he said, will be hard to come by.

‘The horse is out of the barn,” he said. “It’s difficult once benefits are provided to any taxpayers and then to rein them in becomes politically difficult.”

Although not impossible – under the LePage administration and Republican-led legislature, for example, benefits were reduced for state and teacher retirees because pension costs were threatening to consume a growing portion of the state budget.

Katz, of Augusta, said he thinks he knows why the issue has lingered on the back burner.

“It’s a huge issue,” he said “and to me the cause of it is pretty clear to see — because of two-year terms and term limits, we have institutional ADD in the legislature. And we need to figure out a way to work through our disability.

“The kind of long-term planning and analysis that a well-run business would do is tough to see through,” said Katz.

His point is borne out by looking at the legislative committee that commissioned the OPEGA report, the report that has seen almost none of its recommendations followed.

Of the 12 members of that committee, not a single one is in the legislature today.