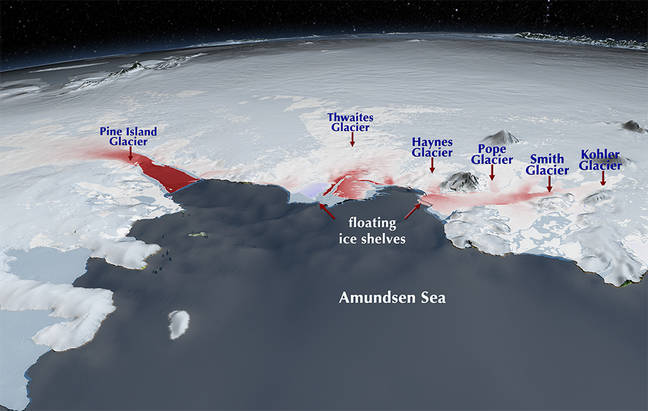

Corks. Plugs. Floodgates. The metaphors used to characterize two glaciers at the edge of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet (WAIS) – Thwaites and Pine Island – are tame relative to the scale of these vast ice rivers.

Thwaites glacier, spanning an area more than twice the size of Maine, is the subject of intense scientific scrutiny, being the “weak underbelly of the WAIS,” according to Brenda Hall, a professor of glacial geology at the University of Maine and a member of a U.S.-U.K. Thwaites research collaboration. “This glacier could undergo a runaway deglaciation.”

Glacial dynamics in a setting 9,000 miles away might strike some Maine residents as irrelevant, but the disintegration of Thwaites glacier alone could raise global sea levels by 1.6 feet.

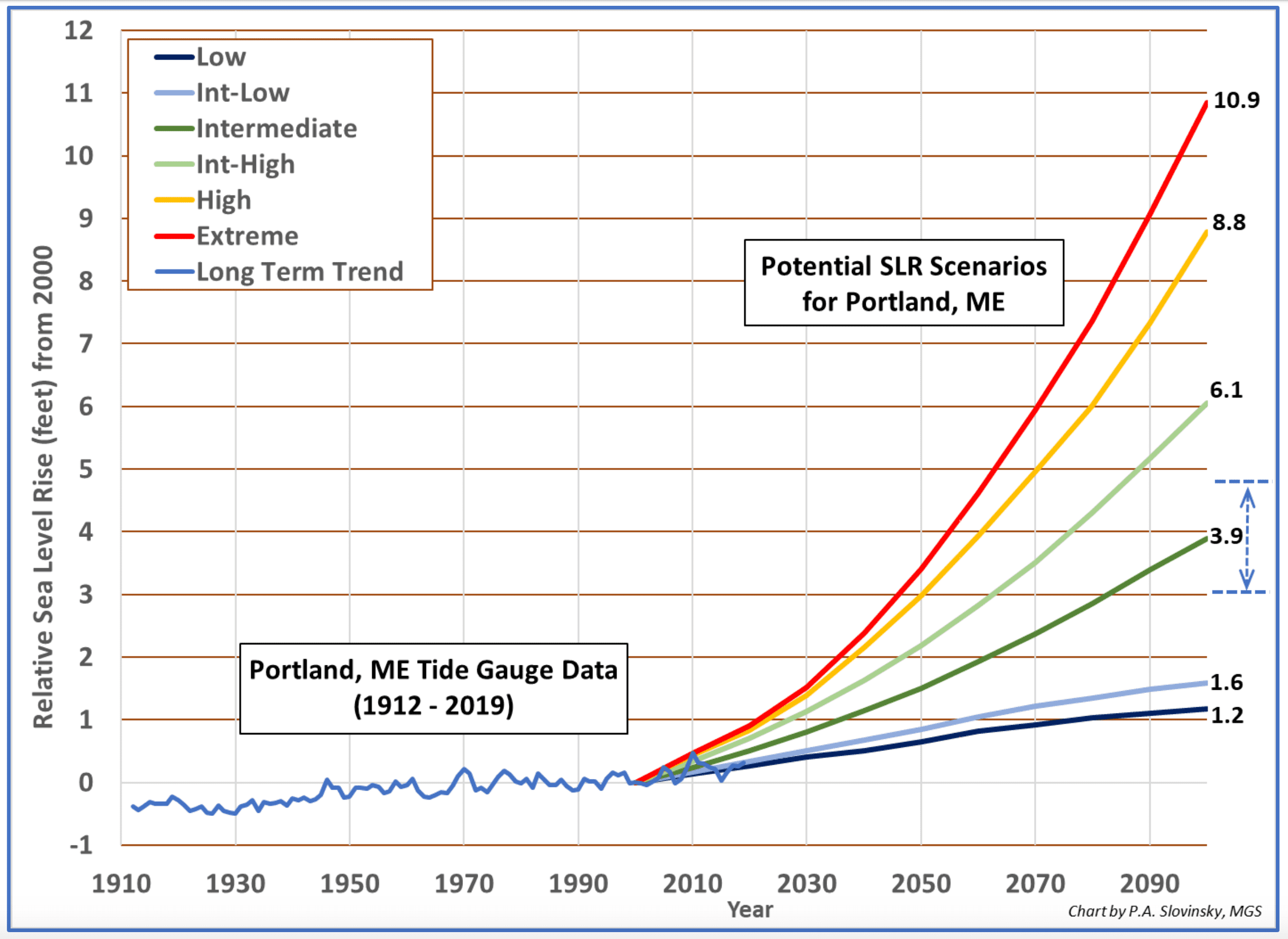

The highest sea-level rise scenario currently mapped for Maine, based on National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration data, is 10.9 feet by the year 2100. That would submerge roughly 130 square miles of land during high tides, according to the Maine Geological Survey (MGS).

NOAA anticipates a very low probability of that “extreme” scenario occurring, but that could change as glaciologists better understand the dynamics of the rapidly changing WAIS.

Because Thwaites glacier rests on continental bedrock below sea level, its degradation could open a path for ocean water to destabilize the much larger WAIS, which holds in its ice enough water to potentially raise worldwide sea levels by 11 feet or more.

Since the 1990s, glaciers in Greenland and Antarctica have undergone what one glaciologist termed a “melting binge” that has kept accelerating. A decades-long warming trend in Antarctica, Hall said, has sparked a sense of urgency in the scientific community about Thwaites’ future: “This is changing so rapidly that we’ve got to get answers quickly.”

According to Scott Braddock, a doctoral student at the University of Maine who did field work at the glacier last spring, “warm ocean water temperature is driving the retreat” of Thwaites. Braddock, Hall and Seth Campbell, another glaciologist at the University of Maine, are working to understand the glacier’s history going back 5,000-6,000 years — sampling rock from beneath the ice sheet and calculating relative sea and land levels — to determine whether Thwaites experienced regrowth following periods of retreat in the past.

If Thwaites did regenerate at times, Hall said, that “would offer more hope” that the current retreat – the glacier is losing an estimated 50 billion tons of meltwater a year – might reverse if air and sea temperatures stop rising. But, she cautioned, “there’s an awful lot we don’t know about how a marine ice sheet will break up and disappear. There may be tipping points, and we may have passed one.”

One of the eight international project teams in the Thwaites research collaboration is looking at how sea water might undercut the glacier and the WAIS, potentially forming marine ice cliffs that collapse under their own weight.

Another team recently made headlines for the first journey of a submersible robot, dubbed Icefin, along Thwaites’ grounding line, where the glacier loses contact with the continental seafloor and starts to float in open water. A preliminary review of the Icefin video footage confirmed for scientists the rapid melting underway there.

Meltwater from ice sheets and glaciers now accounts for roughly two-thirds of global sea-level rise, and that proportion continues to grow. (The other major cause is thermal expansion, the increase in volume of ocean waters as they warm.)

In Maine, “the number of average monthly high-water-level events is increasing and setting records, especially in the past decade,” noted MGS geologist Stephen Dickson. “The three highest levels on record all occurred in the past decade. Those statistics are staggering.”

There is also an upward trend in the frequency of flooding events, observed MGS geologist Peter Slovinsky, with far more “nuisance flooding” during astronomical high tides (when the gravitational pull of the sun and moon reinforce each other).

Sea-level rise is accelerating more quickly than scientists had predicted. To reflect new data, MGS revises its projections every four years and, Dickson said, “they keep going up.”

In 2006, MGS projected a 50 percent probability of a 1.9-foot increase in sea-level rise by 2100. Now, that has risen to a 50 percent probability of a 3.9-foot increase by 2100, with continued increases expected thereafter. Even the one-foot increase that potentially may occur by 2030 could produce more than a 15-fold increase in nuisance flooding, according to MGS.

If the world fails to rein in carbon emissions in coming years, Maine sea-level rise chart lines spike upward: “The business-as-usual scenario is almost 11 feet,” Dickson said. And those projections only account for “where the tides are, not where the storms can reach.” Storm surge can add 2-4 feet to those figures.

Sea-level rise projections don’t factor in the increased intensity of storms associated with climate change, such as the bomb cyclone that hit Newfoundland in January, dropping 30 inches of snow, and Storms Dennis, Ciara and Jorge, which recently pounded the U.K. with high seas, hurricane-force winds and heavy rains.

Big uncertainties remain in Maine’s projected sea-level rise, Dickson noted, because the dynamics of ice sheets in settings like Greenland and Antarctica are not easily predicted. “Ice does not have to respond linearly,” he said. Thwaites glacier has already “retreated off a bedrock high that provided a pinning point,” which helped anchor the glacier, Hall said. That could mean a faster track to the sea and disintegration.

On Feb. 18, the Scientific and Technical Subcommittee (STS) of the Maine Climate Council released a working document with analysis and recommendations based on the latest research. The subcommittee suggested, based on MGS data, that “it is likely” sea level in Maine will rise 3-5 feet by 2100.

In the document’s discussion of sea-level rise, which spans 35 pages, only a few phrases are set in bold. One of them bears noting: “Because of the evolving science regarding potential future contributions to global and regional sea level rise by the Greenland and especially the Antarctic ice sheet, the STS recommends that the Climate Council also consider preparing to manage for a potentially higher sea level rise scenario.”