The sole purpose of the board that regulates pharmacists in Maine is to “protect the public health and welfare,” according to state law. But in thirteen cases over the last decade the board has jeopardized the public’s health by allowing people with a history of substance abuse and theft to hold a license to dispense drugs at pharmacies across the state.

In one case, the state Board of Pharmacy gave a license to an Auburn man despite concluding in their investigation of his past that he “failed to demonstrate that he is of good moral character and temperate habit, as shown by his habitual substance abuse that has resulted in or is foreseeably likely to result in … performing duties in a manner that endangers the health or safety of the public.”

The pharmacist got a job working at two Bangor Walgreens pharmacies, where he proceeded to steal narcotics and ultimately admitted that he consumed the pills while he was working. He was fired, then arrested and lost his pharmacist license.

A Maine Center for Public Interest Reporting examination of state pharmacy board records showed that during the last ten years, 16 Maine pharmacists had their licenses revoked by the state for stealing drugs. Thirteen pharmacists during the same period were allowed by the board to practice pharmacy despite their history of drug abuse and theft. Five of them went on to steal or abuse drugs again and lose their licenses once more.

State regulators even gave one of those repeat offenders his license back one more time. Two and a half years later, that pharmacist was found by co-workers to have snorted a combination of narcotics and cocaine through a straw in the back room of the Augusta pharmacy where he worked.

Almost all of these pharmacists had been drug abusers. In those cases, the Maine pharmacy board required counseling, drug testing and limitations on hours worked in exchange for getting approval to work again.

But even with those strict conditions, one drug crime expert questioned whether Maine regulators were gambling with the public’s safety.

“You have to be very careful about putting them back in a workplace that’s a smorgasbord of the things they’re addicted to,” said John Burke, Commander of the Warren County, Ohio Drug Task Force and a nationally known expert on drug theft. “It’s like making an alcoholic a bartender.”

Normand Turgeon, a pharmacist who was given his license back twice after stealing and abusing drugs but went on to steal and abuse again, said he doubted that he would have ever been able to safely return to dispensing drugs to the public.

The only safe pharmacy job for him would be an administrative one, Turgeon said, “where you don’t deal with drugs, where you never actually see drugs.”

Among those who had their licenses revoked because of drug theft and addiction and then given back are a pharmacist who wrote prescriptions to his dog so he could get the painkillers; a pharmacist who stole Hydrocodone, Alprazolam, Ambien, Zolpiden and Tylenol with Codeine because of what he claimed was “stress” from a new manager at his pharmacy; and an addicted pharmacist who got his morphine “by stealing leftover doses at a home care IV pharmacy” where he worked.

A second chance

The case of Eric A. Johnson of Presque Isle demonstrates the pharmacy board’s willingness to allow someone with a history of theft and drug abuse to dispense drugs to the public.

Johnson graduated from the Massachusetts College of Pharmacy in 1999 and was employed by Wal-Mart Pharmacy until his arrest on July 2, 2003.

“The arrest was brought about by the applicant’s theft of Hydrocodone from his employer’s pharmacies in Houlton and Skowhegan,” Pharmacy Board disciplinary records state. Hydrocodone is a narcotic pain reliever.

The board suspended Johnson’s license on July 8 and in a consent agreement effective Sept. 9, 2003, Johnson agreed to the revocation of his license.

Johnson began substance abuse counseling “which he successfully completed after 28 days at a facility located in Ft. Fairfield,” according to state records. He then faced legal proceedings related to his theft and was convicted on June 9, 2004. He spent 21 days in jail, was ordered to pay $2,000 in restitution and placed on probation for one year.

The records describe how Johnson entered a halfway house for substance abusers in Bangor in 2005, went to Alcoholics Anonymous meetings and got counseling. He got a job as a delivery truck driver in Aroostook County and then “suffered a relapse and began using Oxycodone and Methadone, and joined a ring of users who stole property to support their opiate habits.” Oxycodone is a narcotic pain reliever even stronger than Hydrocodone.

Johnson was arrested again on Oct. 29, 2005, sentenced to jail for 21 days, fined and put on probation.

Three years later, Johnson petitioned the board for reinstatement of his license, saying he was currently receiving counseling at least monthly, attending AA sessions and meetings with other medical professional with drug problems. He said he had support from family members and had “terminated his relationships with drug users.”

Johnson told the board he had signed a five-year contract with the Medical Professionals Health Program, or MPHP, the Maine Medical Association’s support program for substance-abusing medical professionals. The contract required him to go to counseling, allow urine tests and blood monitoring and not use alcohol or drugs.

The pharmacy board voted unanimously to reinstate Johnson’s license, concluding “that Eric Johnson has been rehabilitated to the extent that he has earned the public’s trust, and reinstating his license to practice pharmacy would not pose a threat of harm to the public if the following conditions are complied with.”

The board’s conditions echoed the ones from the MPHP contract and also limited the amount of time each week Johnson could work as a pharmacist.

Johnson did not respond to numerous attempts to reach him for comment before publishing deadline.

Lori McKeown, a pharmacist who was president of the pharmacy board when Johnson got his license back, did not respond to requests for comment. But Joseph Bruno, the current head of the board, said that the board is inclined to give a second chance to pharmacists who are addicted, who steal – and who then turn their lives around.

“A lot of people screw up one time, not only in medical professions. As a society, are you willing to hold that one mistake against that person for the rest of their life?” said Bruno. “They’ve gone to school for a minimum of five, six years. You don’t want them to waste a career.”

A contract with the Maine MPHP weighs heavily in the pharmacist’s favor, said Bruno. The pharmacy board gives $20,000 a year to the substance abuse program.

“When pharmacists have the opportunity to go to the MPHP, we rely on those professionals to tell us whether or not those folks have actually rehabilitated themselves,” Bruno said.

Dr. Lani Graham, who runs the MPHP, says the relapse rate in her program is “fantastically low,” only 10-11 percent over the last three years.

“I wouldn’t hesitate for a minute as a patient to seek the help of any of the professionals that are in our program,” she said, adding that the participants in the program are her “heroes and heroines.”

Patient harm

But others say that there’s a risk to putting formerly addicted pharmacists back to work in a place where drugs are the focus of their work and where just one slip-up — the wrong medication or wrong dosage — can be dangerous, even fatal to a patient.

“These are the health-care professionals who are filling our prescriptions,” says Charlie Cichon, president of the National Association of Drug Diversion Investigators.

“Mistakes,” said Cichon, “lead to patient harm.”

Rodney Larson, founding dean of Husson University’s School of Pharmacy, said that not every pharmacist will make it through an addiction and back to health.

“I’ve seen pharmacists come back and become productive members of the profession and society after treatment, and I have seen pharmacists who have left the profession,” he said. “I’ve known pharmacists who have died after overdoses — they can handle recovery or not and some people can’t. Unfortunately, those people tend to get deeper in trouble.”

Eric Johnson is one of the cases where the board’s decision illustrates Bruno’s point – a second chance can work out. Johnson’s license was recently renewed, a sign the board has seen no problems.

Normand Turgeon is one of the cases that went the other way. Twice.

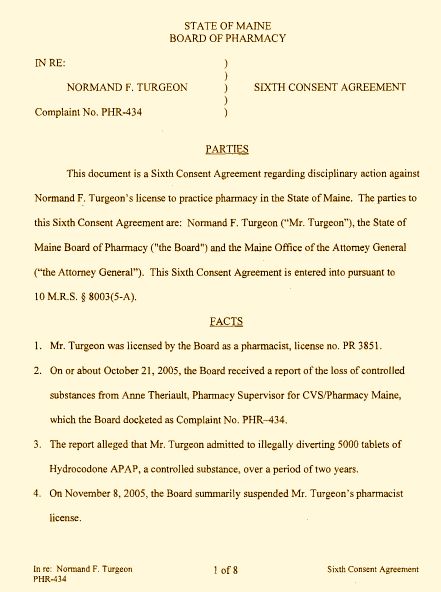

In October, 2005, CVS Pharmacy in Lewiston alleged to the pharmacy board that Turgeon had illegally diverted 5,000 tablets of Hydrocodone APAP, a controlled substance, over a period of two years.

In early November, the board suspended Turgeon’s license and in December, Turgeon, the board and the Attorney General’s office signed an agreement in which Turgeon admitted to diverting Hydrocodone APAP from CVS and failing to disclose a criminal conviction as required in his 2002 renewal application. His license was revoked and he was fined $100.

The next month, Turgeon asked the board to give him back his license. In mid-February, 2006 the board voted to give it back, while imposing conditions, including urine screenings and counseling. He was ordered not to take prescription medications without a prescription.

In July, Turgeon asked the board to relax those conditions and allow him to see his “treating specialist” less frequently. The board agreed.

But several months after the board made that agreement, they learned that Turgeon had tested positive for barbiturates in June, August, September and November. That led the board in February, 2007 to revoke Turgeon’s license again, and fine him $1,500.

Seven months later, Turgeon requested reinstatement of his license yet again. In December 2007, the board voted to give him his license back, with conditions. Several months later, Turgeon convinced the board to lighten the conditions yet again.

‘Couldn’t trust myself’

On April 9, 2010, Turgeon was working as a pharmacist at Kennebec Pharmacy and Home Care in Augusta when he got into trouble again.

“In the medication storage room, where Mr. Turgeon had been working, an employee found a cut straw and a powdery substance,” pharmacy board records state. “The powder later tested positive for hydromorphone, hydrocodone and cocaine. … Mr. Turgeon ultimately admitted to Investigator Tom Avery that he had ingested the powder by snorting it through the straw, and that he had been doing so for months. Mr. Turgeon also admitted to drinking liquid morphine overfill.”

Once again, Turgeon’s license was revoked. He has not reapplied for his license.

Turgeon now works in customer service for a retail company and participates in Alcoholics Anonymous. He said he should not have been granted his license back just three months after it was first suspended.

“I look back now, I was very happy to get it back, but it was too soon,” he said. “Of course, you know the person who’s out of work wants to get back to work even if they’re not ready. As I look back now, the period needs to be longer,” in order to demonstrate the pharmacist’s commitment to sobriety.

He said that after losing his license the second time, the six-month interval between losing it and applying to get it back was enough to determine he was trustworthy.

“I felt at that time that I was ok, but it turned out not to be true,” he said.

After the final revocation of his license, he “thought about going back for the longest time, but then realized, ‘I couldn’t dispense drugs anymore, I couldn’t trust myself.’”

Pharmacy board chair Bruno could not comment on particular cases, but said about Turgeon’s case, “That was before my time. The makeup of the board means something, and the current board you have now is an older and wiser board.”

If a pharmacist had gotten his or her license reinstated and then failed to pass a drug test, Bruno said, “that would not sit well with me.

“I would have said ‘You’re done. It’s pretty clear, this is what you must do, if you think you are above it all.’”

Bruno said the board under his leadership since March 2011 has increased the punishment for many pharmacist and pharmacy technicians’ violations. And it has only granted one of the two requests for reinstatement by pharmacists who lost their licenses for stealing.

“We are much harsher than past boards, because we do not want to see impaired pharmacists out there and, frankly, it’s a stain on the profession,” said Bruno.

This was the second of our two-part series: Rx for Theft. Freelance reporter Claire Cameron contributed to this report.