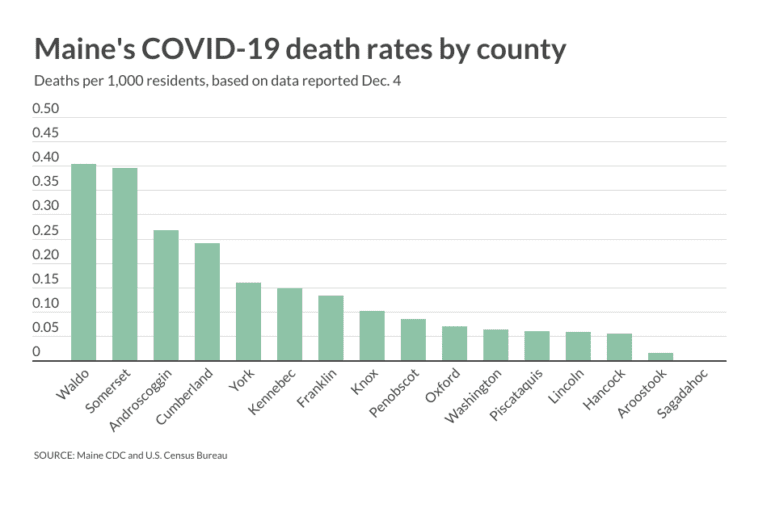

Somerset County, which recorded its first COVID-19 death in August, now has Maine’s second-highest death rate after a statewide surge last month.

Waldo County has the highest, but 14 of its 16 deaths were before June.

November was Maine’s deadliest month with 67 deaths, accounting for nearly a third of all COVID-19 deaths during the first nine months of the pandemic. On Dec. 1, Maine recorded another 20 deaths — the state’s highest daily death toll — but that included some delayed reports from over the Thanksgiving holiday, according to the Maine Center for Disease Control and Prevention.

After maintaining relatively low numbers of new COVID-19 cases throughout the summer, Somerset County experienced a spike in late October. In November, 12 residents died in the rural, western Maine county, giving it the highest death rate per capita in the state that month.

A total of 20 people have died in Somerset County: 1 of every 2,524 residents, or just below 0.4 deaths per 1,000 residents, as of Dec. 4. There have been a number of outbreaks, including at the Maplecrest Rehabilitation and Living Center in Madison, where six people died after an outbreak linked to an August wedding in Millinocket.

However, many Somerset residents who died were not living in nursing homes or other community living centers, according to Maine CDC Director Nirav Shah.

“We are looking more deeply into that to try and determine if there were other unifying factors. Whether there is, for example, just in a demographic sense, an older-than-average age in certain counties and whether that could be generating more individuals dying,” Shah said on Dec. 2.

Waldo County, with a total population of 39,715, has the highest cumulative death rate of 1 for every 2,482 people. But 13 deaths were linked to an April outbreak at Tall Pines Retirement and Healthcare Community in Belfast. Waldo County recorded two COVID-19 deaths in November.

Cumberland County, the state’s most populous county (295,003), was hit hard early in the pandemic and maintains the highest number of confirmed cases (3,404) and deaths (71). But its death toll as a proportion of the county’s population, at 1 death for every 4,154 people, is lower than Somerset County (total population of 50,484). Cumberland County had one death last month.

In York County, which has the second-highest death toll of 33, the proportional rate is 1 death for every 6,292 people.

Shah warned last month that this wave of COVID-19 cases is fundamentally different than in the spring, when new cases arose in urban and populous areas, after large gatherings and among older populations. Now, outbreaks are occurring from smaller gatherings, in less-populated states, in rural areas and among younger people.

Matthew Fox, a professor of epidemiology at Boston University, told The Maine Monitor that time is the primary reason it took longer for outbreaks and deaths to reach rural communities.

“It is much easier for spread to happen in cities because so many people are around,” Fox said. “It takes longer for it to make its way into the rural areas and rural areas tend to have less hospital capacity, so there are more delays to getting care.”

Deaths are “largely, though not entirely” related to the number of cases in a state, Fox said. “I say largely because some states do better in terms of preventing cases from turning into deaths.”

Maine’s death rate is 0.3 per 100,000 people, according to COVID Act Now. South Dakota had the highest death rate this week with 3 per 100,000 people. The national rate was 0.6 per 100,000.

As of Dec. 4, 224 Mainers had died from COVID-19. Nationally, about 277,000 Americans have died from COVID-19 and some experts predict the U.S. will soon surpass 3,000 deaths a day, according to Reuters. That’s equivalent to the death toll from the Sept. 11, 2001 terrorist attacks, every day.

However, the best way to understand how COVID-19 is spreading in Maine is to look at cases and hospitalizations rather than deaths, Fox said.

“Deaths are a lagging indicator, so it takes weeks to see a problem show up in deaths,” he said. “(The number of) cases is a better indicator, but that is dependent on testing, whereas hospitalization, also a lagging indicator, isn’t.”

As of Dec. 4, Maine ranked 51st for new daily cases per capita with 13.7 per 100,000 people, higher only than Hawaii and the Northern Mariana Islands, according to COVID Act Now. South Dakota, which was ranked first, was eight times higher with 116.4 new daily cases for 100,000 people.

Fox said it’s important to also consider the age of people who died “because if one state has lots of people who are older being infected, they will see more deaths and that tells us we need to protect those who are older.”

More than half of the deaths in Maine have been people 80 and older, according to the CDC. About 94 percent of people who died were 60 and older.

“Things are getting worse and the holidays are likely to make that even worse,” Fox said shortly after Thanksgiving. “We should be prepared for that, as I do think (in) the next few months we will see a steady increase in cases and deaths.”