The snowpack crunched underfoot in early February as Mica Adler walked across an icy field toward her tiny house in the woods outside Presque Isle.

She was on her way to retrieve dinosaur-patterned boots and other items that belonged to her then four-year-old son, whom she was set to see for the first time in months.

She had lived in the one-room home with the boy — just the two of them, off the grid. That ended in March 2024, when he was removed by the state after an incident in a supermarket parking lot.

A woman had called the police and reported that she had witnessed, through her side view mirror, Adler punching her child in the lower back — something Adler maintains was a spanking because the boy had run near traffic.

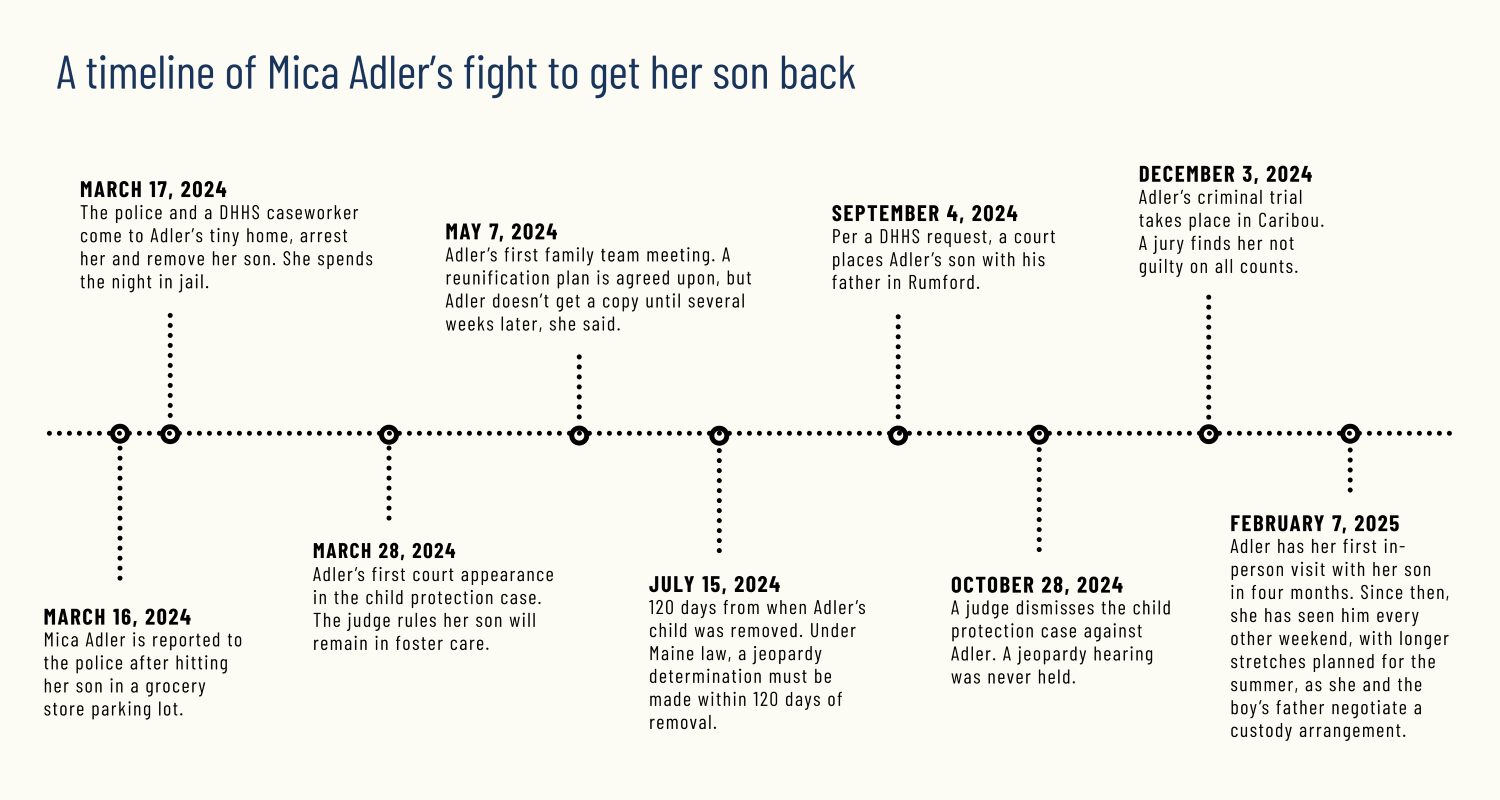

The day after the incident, Presque Isle police charged Adler with three crimes, including domestic violence aggravated assault, a felony carrying a sentence of up to ten years in prison.

That same day, Maine’s Department of Health and Human Services took her son away.

In its court petition to take the boy into custody, the department caseworker wrote that he was in “immediate risk of serious harm due to physical abuse and neglect by his mother,” citing not only the incident in the parking lot but conditions at the tiny home, as well as the boy’s tooth decay. The court granted the petition and placed the boy in a foster home.

Since then, Mica has been fighting to get him back. Late last year, the department dropped the child protection case against her. Then a jury found her not guilty on all the criminal charges.

But she has yet to regain full custody of her son.

“It wasn’t a strong enough case for the department to bring to jeopardy,” said attorney Molly Owens, who represented Adler in the child protective case, referring to the jeopardy hearing in which a judge rules whether a parent is a threat to their child. “She won her criminal trial, and yet, the long-term ramifications are that she doesn’t have her child.”

Several tragic child deaths in the past decade have gotten significant media attention in Maine and prompted criticism that the state fails to remove children from dangerous living situations. Likewise, the state’s child welfare ombudsman has published several annual reports highlighting the department’s poor decision-making around child safety.

But many lawyers and advocates working in child welfare say they see something else: the criticism has led to a “foster care panic.” They argue the state is now investigating too many parents, removing too many children, and breaking apart too many families in an effort to prevent the next death. They argue that these efforts overload the system, making children less safe.

The most recent federal data shows Maine has become an outlier in the United States. Between 2019 and 2023, the national foster care population fell by nearly 20 percent as most states embraced ways to keep families intact. Maine’s foster care population increased 17 percent over that same period, more than any state. In 2023, Maine took children into foster care at a rate nearly double the national average.

But any effort at understanding whether the system is too cautious when deciding to remove children, as some argue, or too overzealous, as others claim, is hindered by its secrecy. Cases are confidential, and decisions made by the department and judges are made behind closed doors.

Adler’s story offers a rare glimpse inside the system. Her combined criminal and child protection cases illuminate the power the state can bring to bear on families, the tough calls child protection workers must make with imperfect information, the hurdles parents must overcome to win their children back, and the blurry line between unconventional parenting and child maltreatment.

This account is based on police reports, body camera and surveillance footage, court filings and transcripts, and DHHS records provided by Adler, as well as interviews with Adler, her lawyers, and the child’s father. DHHS and the Attorney General’s office, which represents the department in court, declined to answer questions about the case, citing confidentiality laws.

At the center of it all is Adler: a woman who eschews convention. DHHS records indicate she did everything the department required for her to reunite with her son. She refused to accept settlement offers from both the department and prosecutors. Despite her legal victories, she lost her child. She believes what was done to her was an injustice, and hopes her story can help others.

“They think that people in my position can be taken advantage of,” said Adler. “Not everyone is going to roll over.”

The parking lot incident

On March 16, 2024, Adler drove with her son to the Graves’ Shop ’n Save in Presque Isle to buy a slice of cheesecake for her birthday, which was two days away. It was Saturday, and her three-year-old son was looking forward to running around the playground at Riverside Park, bouncing with energy as he held his mother’s hand as they walked into the store.

Adler looked for some cheesecake in the bakery section, and not finding anything, looked in the frozen section. The boy demanded ice cream. Denied, he threw a tantrum, Adler remembered.

They were in the store for less than ten minutes, then walked back out into the parking lot. What happened next would profoundly alter their lives.

As they approached Adler’s truck, an SUV drove toward them down the lane and the boy ran ahead of his mother. Moments later, Adler bent down between the vehicles and hit her son — a spanking, in her telling, to teach him not to run off near traffic like that again.

The woman driving the SUV parked and called the police, explaining that she had seen Adler “lay a child…on the ground and hold her down while she punched her in the lower back/butt,” according to her statement, mistaking the boy for a girl.

Police found Adler at the park more than an hour later, sitting at the base of a jungle gym while her son played.

Body camera footage shows an officer telling Adler about the report they’d received. She denies the accusation and tells the police to check the parking lot surveillance footage.

Meanwhile, two other officers interview the boy. Then they consult with one another, away from Adler and the child.

“Kid seems fine,” one officer says.

An arrest and removal

The next day, Presque Isle police went to Adler’s home, accompanied by a DHHS caseworker.

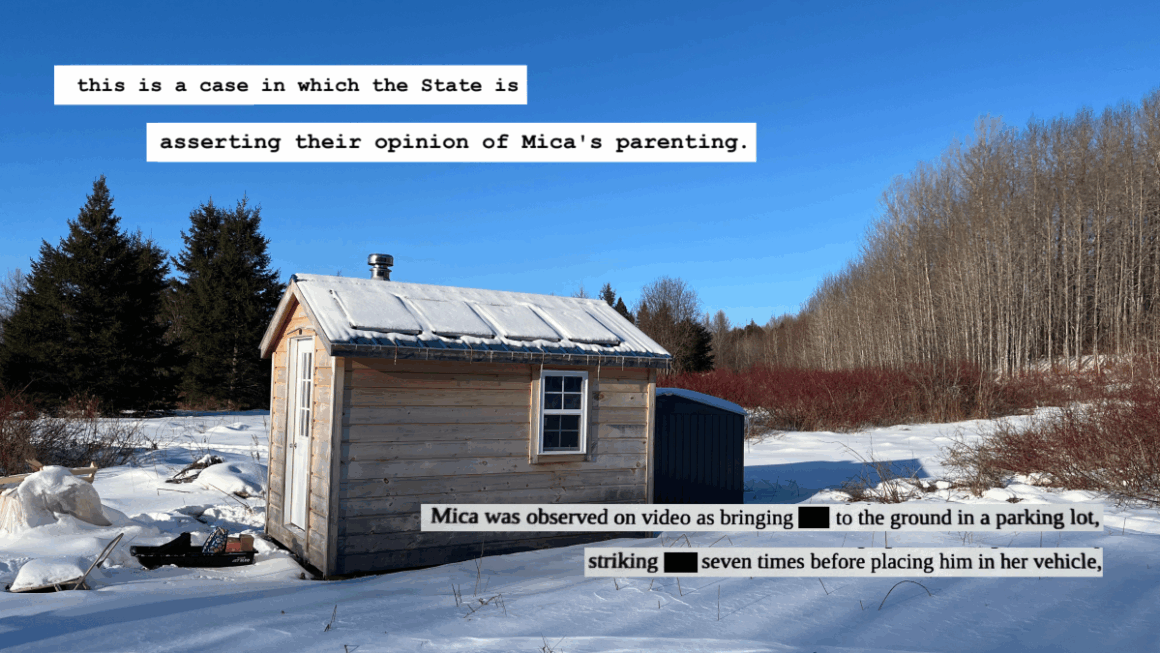

The tiny house, which she set up with the help of her Amish neighbors and their horses, sits on 41 acres she owns outside Presque Isle, a slice of property about a mile from the road down an ATV trail sometimes passable by car, depending on the weather.

Her goal was to build a homestead there, where she could be self-sufficient. She had a well for water and solar panels for electricity, with plans to build a geothermal heating system for warmth.

“It was supposed to be freedom,” she said.

She and her son, whom she was raising alone, had moved there from Rumford in the summer of 2022, and had at first lived in a makeshift yurt. Adler took the boy on a road trip across the south to avoid the Maine winter, she said, visiting children’s museums and friends and often sleeping in her car. The next summer, the tiny house was delivered.

Adler acknowledges that the life she was building there was unusual, but said her son was safe and happy. She planned to enroll him in public school when he was old enough, allowing her to work and eventually afford to build a larger house on the property.

On the drizzly March day the world came to their doorstep, a police officer noted in his report that it appeared Adler and the boy were nude, and put on clothing before answering the door.

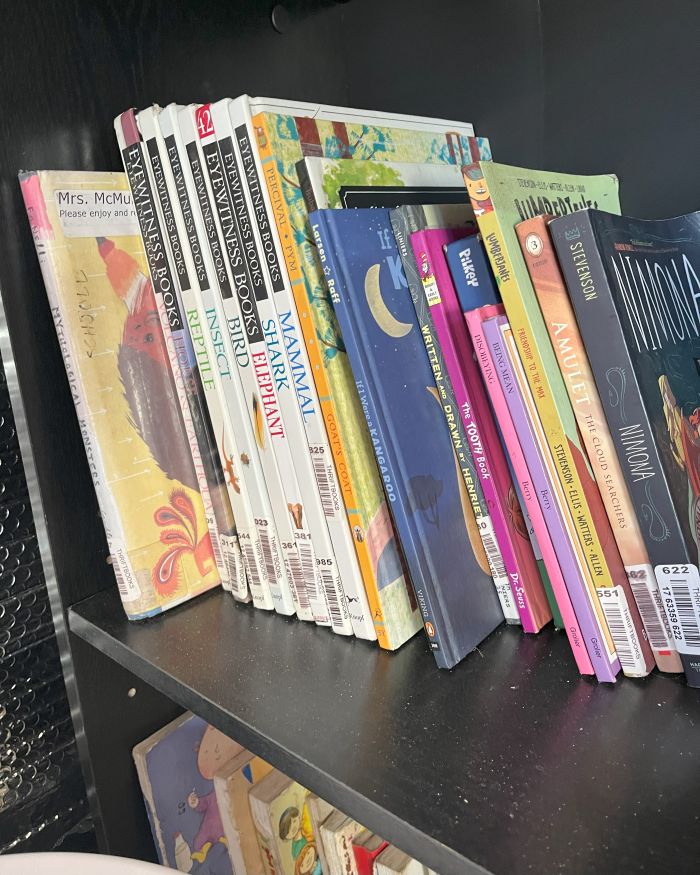

It’s true, they were often naked and rarely bathed, Adler later told The Monitor, explaining that when you smell like nature, the blackflies and mosquitoes don’t notice you much. A bucket with a liner served as their toilet. They washed with wipes, and would shower when they traveled to Rumford, where she owned and rented out a house, for the boy’s medical appointments. The boy loved being outside and picking raspberries nearby, Adler said. On rainy days, they read and drew pictures.

In police body camera footage, Adler’s son shows the visitors his drawings and asks if they have any stickers. Adler looks tired and teary as she answers questions about her life with her son from her seat on the bottom bunk.

“It’s frustrating because you’re the third person I’ve had these conversations with,” she tells the caseworker.

In May 2023, shortly after she returned to Maine from the road trip, DHHS investigated Adler following an incident in which she was observed yelling at her son and throwing him into the car and “due to concerns that she and [the boy] were residing in their car,” according to DHHS records.

A brief DHHS summary in her case files indicates the investigation was closed when concerns about the two living in a car were alleviated.

Five months later, DHHS was involved with Adler again, this time “due to concerns that Mica and [her son] were residing in a shed with no refrigerator and without details on the condition of the shed.” The investigation was closed without findings, and without a visit to Adler’s tiny home. DHHS outlined its expectations: “Mica will continue to provide adequate care and shelter for [the boy], and ensure her home has heat and food at all times.”

Bodycam footage from the March visit shows there was heat and food. But the inside of the house was messy, with trash bags of clothes on the floor. The caseworkers ask about a container made for urinating during camping trips, which Adler says they use when it’s cold, and when the boy’s last dentist appointment was — a year ago, as she had to cancel his last one because of car troubles.

Adler packs the boy’s things, asking if he wants his car book or his dinosaur book.

“My love, this will be your first sleepover. Isn’t that exciting?” Adler says. Then, quietly: “I know it’s not the best circumstances.”

The caseworker, Danielle Deprey, appears sympathetic, explaining that the boy will be placed with a licensed caregiver and that a “permanency caseworker” will work with Adler on reunification.

“Living off the grid isn’t a crime,” she tells Adler. “We just want to make sure to put things in place for you.”

A petition to remove the child from Adler’s care was filed later that day. In the affidavit attached to the court petition, Deprey wrote that the child “is in immediate risk for serious harm due to physical abuse and neglect by his mother Mica Adler.”

The petition cited the incident in the parking lot as well as the boy’s “significant tooth decay” and the fact that Adler “reported using only wipes to clean their bodies as there is no running water.”

The petition also mentioned Adler’s “history of legal charges related to substances in the state of South Dakota in 2015/16,” referring to a charge of possession of hallucinogenic mushrooms that was dropped by prosecutors. As part of the deal, Adler pleaded guilty to a misdemeanor possession of marijuana charge. The petition also cited “a history of mental health that is currently untreated,” a reference to Adler’s admission that she had been feeling depressed and had seen a therapist as a child.

“I don’t think there are many people that could honestly say that they never struggled with depression,” Adler later said.

Judge Rob Langner read the petition and signed an order that took the boy into state custody and placed him with licensed resource parents Diane King and John Labelle in Houlton, about an hour’s drive south.

Adler was booked on charges that included Class C endangering the welfare of a child, Class C assault, and domestic violence aggravated assault Class B, a crime that can result in up to 10 years in prison.

She spent the night in Aroostook County Jail and was released the next evening, her 34th birthday.

‘I do not have any concerns with her safety as a parent’

After leaving jail, Adler started to research how to navigate the system in which she and her son were now ensnared. In doing so, she realized there is a paradox at the heart of the child protective system: the department demands collaboration, but regaining custody of one’s child often requires resistance.

“There’s this strange kind of dichotomy,” Adler said. “You have to allegedly work with DHHS to get your kid back, but in reality, you have to fight against DHHS in court to get your kid back.”

Her first court appearance in the child protective case was at what’s called a summary preliminary hearing, where a judge decides where the child should live while the case moves forward. Adler’s took place on March 28.

She expected the boy to be returned to her. But the judge ruled that the boy would remain in foster care.

She was able to see her son during supervised visits in Houlton. She brought food, books and toys, and tried to ignore the supervisor who took notes on her interactions with the boy. At most, Adler was getting two visits a week. But sometimes staffing shortages or logistical problems meant weeks passed without a single visit, she said.

At one point early in the case, a police report noted that a DHHS caseworker supervising the visits had concerns about the fact that Adler and her son had often been naked, and that he seemed familiar with anatomical terms for private body parts. (Adler said she taught her child these terms because sexual abuse prevention specialists recommend doing so.)

The department referred the boy to a forensic interview, which are used to gather information about possible sexual abuse. There are no details about this interview in the DHHS files reviewed by The Monitor, and there were no formal allegations made. (Adler’s lawyer later said that had there been any findings, the department would have introduced them into the case.)

The supervised visits occurred as she waited for her first family team meeting, where parents, their attorneys (almost always court-appointed), a guardian ad litem (a court-appointed attorney who advocates for the best interest of the child), and representatives from the department and the attorney general’s office work out a reunification plan, which outlines the steps parents must take to get a child back.

Weeks passed after the first court hearing and no meeting took place, despite Adler pushing for one. Adler’s first team meeting was on May 7. It took another several weeks before she got an official copy of the plan that had been discussed at the meeting, she said.

The plan required her to “participate in a mental health assessment” and follow all the provider’s recommendations, complete random urine screenings, attend visits with her son and implement the supervisor’s feedback and participate in parenting courses.

Adler had already begun working on many of these steps. She started seeing a therapist she found without waiting for a department referral, started taking parenting classes and submitted urine samples for drug screens.

The plan also required that “Mica’s home will have running water and bathroom facilities. Her home will be free of any safety hazards.”

But Adler had a hand-pump-operated well at the property all along, she said. A few months after the removal, the department visited the tiny home again and acknowledged that she had running water on site, according to an email exchange viewed by The Monitor.

She added a shed to store the bio bricks she used for heat outside the house, upgraded her solar energy system, and added safety features to the stove, as well as a fridge, freezer and composting toilet. She also added shelves and a bookcase.

In July, Adler’s therapist wrote to the court that “Mica has engaged in treatment to the best of her ability and has worked earnestly on her treatment goals to reunify with her child.”

“I do not have any concerns with her safety as a parent,” the therapist wrote, noting that Adler had committed to using “additional parenting strategies” in place of “using spanking as discipline.”

The only diagnosis the therapist gave Adler was “adjustment disorder with depressed mood,” which was “brought on by her child being removed from her care.”

Allegations of abuse in foster care

The boy lived with four different foster families during the seven-month case, according to Adler.

She found out her son had been moved from his first placement when a caseworker called and told her the department had received a report that one of the foster parents — also called resource parents — had slapped the boy in public, Adler said. The boy was relocated from Houlton to a new foster placement in Grand Isle.

Months later, Adler asked the department for records related to the incident. In a text exchange, a caseworker wrote that “we can’t give those records is what I’m being told…I don’t control the licensing stuff and not sure who decides that.”

Adler pushed back.

“Surely I have a legal right to the information about my son allegedly being assaulted in your department’s custody,” she replied. She never received any more information about the alleged incident.

(A spokesperson for the attorney general’s office said that parents are entitled to records related to abuse while in foster care.)

Adler also said she believed the foster family held onto roughly $1,000 worth of personal items: a handwoven wool blanket, a stuffed dinosaur she had gotten her son for his first Christmas, as well as expensive OshKosh and Carhartt clothes she bought during Black Friday sales.

“They’re like ‘pack up your child’s most sentimental stuff’ and then the foster family just resells whatever they want,” Adler said.

(The Monitor was unable to contact the foster parents: phone numbers listed in court documents were either disconnected or went directly to a voicemail box that had not been set up. According to DHHS, the parents are no longer licensed to provide foster care in Maine.)

Adler’s son stayed at the second foster home for a short time before he was moved again because the foster parent had to travel, Adler said. After the parent returned, the boy was moved back.

Shortly after, however, the foster parent decided that she needed a longer break, and Adler’s son was moved again to his fourth foster home in Mars Hill, 20 minutes south of Presque Isle.

Contemplating jeopardy

By July of 2024, nearly four months after the boy was removed, it seemed to Adler that she was on her way to getting her son back.

In a family team meeting on July 8, a DHHS caseworker laid out a plan: Adler’s visits with her son would move to a lower level of supervision, and then she would get weekend visits. If things went well, Adler recalled, by the end of August she would get her son back as part of a trial home placement.

But at the next family team meeting on July 29, an assistant attorney general said none of that was happening unless she waived her right to a hearing, Adler said.

The assistant attorney general said Adler needed to take responsibility for her actions to prove she was ready to parent her child, according to Adler. “And the only way that she thought I could show that I was taking responsibility was by signing the jeopardy agreement,” she said.

Her impression was that without a jeopardy finding, the case wouldn’t move forward.

(A spokesperson for the Maine Attorney General’s Office, Danna Hayes, wrote in an email that “neither the Department nor the AG’s Office would ever ‘refuse’ to engage in reunification because a parent would not agree to a jeopardy proposal.”)

The department had been trying to get Adler to sign a jeopardy agreement since the start of the case. The agreement is analogous to a plea deal in a criminal case. By admitting jeopardy, a parent might get favorable terms from the department and both sides can avoid an adversarial hearing.

But once a jeopardy finding is made against a parent, they are added to the department’s child abuse registry. Anyone on the registry is unlikely to ever pass a background check for a job around children. Adler, who had a bachelor’s degree, had thought about teaching middle school math or science. If she agreed to jeopardy, the option to teach would likely disappear.

Agreements are usually reached because both sides have something to gain. But in this case, it was unclear to Adler what she would receive in return for waiving her right to argue her case before a judge.

“It pretty much boiled down to the appearance of being cooperative with this entity, who was holding my child from me,” Adler said. But it would require “giving up my access to court, which is the only recourse I have if I think this entity is treating me unfairly.”

Adler wanted a second opinion. She switched attorneys, securing Molly Owens, chief of the Parents’ Counsel Division of the Maine Commission on Public Defense Services.

Owens told Adler she should only agree to jeopardy if the department said it would immediately place her son back in her care. Since that wasn’t on the table, Adler refused to sign. A jeopardy hearing was set for the end of October, more than 200 days after the boy’s removal, and eighty days after Maine’s 120-day legal deadline for reaching a jeopardy finding.

‘An ongoing relationship of some sort’

Adler had been determined to raise her son alone, and had not listed a father on the birth certificate. Initially, she told caseworkers that the father was a sperm donor. But faced with the threat of criminal contempt charges, she admitted that the father was a man named Jacob Santillo, whom she had been friends with in Rumford.

In August, a DNA test confirmed paternity, and soon after, the state began efforts to place the boy with him.

She said her initial lie about the boy’s paternity was to honor a deal they had made: Santillo would impregnate Adler, giving her a child without the high cost of a sperm bank, and Adler would never name him as the father, thereby ensuring he would never have to pay child support. But Santillo could still see the boy and be in his life, she said.

Santillo disputes Adler’s story. He said the boy was a product of a one-night stand with a friend, and although he knew of the boy, he did not know he was the father.

When the boy was taken into custody, Adler texted Santillo to let him know, saying that though she promised she’d keep his identity a secret she wanted to give him a chance to take care of the child, text messages viewed by The Monitor show. Santillo did not respond, and Adler texted him a few days later to tell him the court had made her reveal his identity.

“I didn’t really believe that that was the truth,” Santillo later told The Monitor. “So I said, ‘Alright, well, if that’s the case, I’ll wait to hear from the court.’”

A judge ordered a paternity test on April 25. But Santillo said he wasn’t notified until early August, when he was served with a court order at work. He doesn’t understand why it took three months to contact him about the case, months in which the boy was in foster care.

“It was obscene to me,” he said.

In an August report, the guardian ad litem, former Maine Attorney General Michael Carpenter, called the situation a “hot mess,” and noted that he didn’t believe Santillo’s description of events.

Carpenter wrote that he had read text messages between the two that “clearly shows that Mr. Santillo knew of [the boy’s] existence, never suggested the child was not his, was offered the opportunity to come forward after the child went into State custody and has lied about the nature of his relationship with Ms. Adler,” Carpenter wrote.

(To this, Santillo said: Carpenter “doesn’t know the facts. He doesn’t know me.”)

Carpenter went on to argue that Santillo’s parental rights to the boy should have been forfeited under the state’s laws around child abandonment, since he knew the boy went into foster care and didn’t get involved.

But DHHS argued that his rights were still intact. Its view was that it had found the boy’s other parent, who now wanted to raise the boy with his wife and two other children.

The court agreed with the department, and on September 4, Santillo was granted custody.

After the boy came into his care, he was angry to learn the boy wasn’t vaccinated and horrified at the state of the child’s teeth, which he said were “rotted out.”

“She hid out in the woods for three years with this child and neglected the hell out of him,” Santillo said.

He also had concerns about inappropriate sexual behavior and had the boy undergo a forensic interview through Spurwink, he said. No disclosures were made.

To Santillo’s surprise, after they placed the boy with him, the department’s representatives said that they would be dropping the case against Adler, leaving them to fight over custody with private attorneys.

“I’m like, ‘whoa, whoa, what do you mean? You’re dropping the case?’ They just handled it completely wrong,” Santillo said. “For her to get off scot-free on everything and then be able to have involvement in our son’s life is beyond me.”

Santillo decided to ask the court in Rumford for a protection-from-abuse order against Adler on their son’s behalf.

The judge issued a temporary protection order, writing that Adler was prevented from having any contact with her son “except as allowed by DHHS” and Santillo.

The order was later extended for a year, but the restrictions on contact between Adler and her son were removed. The order only restricted Adler from abusing her son or entering Santillo’s house, court records show.

In late October, Carpenter filed his final guardian ad litem report to the court. He noted that Santillo had been an “appropriate and protective parent,” but that Adler’s “ability to continue the close connection to her son has now been complicated by the distance to Mr. Santillo’s home as well as Mr. Santillo’s attitude toward her.”

“While I might have my own view of Ms. Adler’s lifestyle, she was the only parent to [the boy] for several years,” he wrote. “To cut [the boy] off significantly from his mother would not be in his best interest.”

A week later, on October 28, a judge granted the department’s motion to drop the case against Adler. It had placed Adler’s son in Santillo’s house, 270 miles from his mother, and completed its mandate to safely reunify children with their parents.

‘The offer was just insane’

Meanwhile, Adler’s criminal case was proceeding. Even after the most serious charge was dropped, she was still looking at five years in prison.

The state offered Adler a plea deal, her criminal defense attorney, Mackenzie Deveau, recalled: plead guilty to two of the charges, get two years of probation and 90 days in jail (with another 27 months of jail time suspended).

The offer seemed abnormally harsh to Deveau. As a public defender, she has represented men charged with domestic violence who received more favorable plea offers, she said.

Deveau tried to negotiate with the prosecution, but there “was no budging.”

“There was no discussion,” Deveau said. “And the offer was just insane.”

Adler’s trial took place on December 3 at the Aroostook County Courthouse in Caribou.

The case hinged on whether the parental control justification in Maine law applied to what Adler did in the grocery store parking lot. The statute says that parents can use a “reasonable degree of force” to prevent or punish a child’s misconduct so long as it does not result in anything more than “transient discomfort or minor temporary marks on that child.”

The boy had no bruises or injuries, according to the doctor who examined him the day after the incident.

But the prosecution argued that Adler struck the boy for a reason other than his misconduct, which would nullify the parental control justification.

“Ms. Adler was not disciplining him for something that he did wrong, but acting out whatever emotional experience she was having herself in that moment,” Assistant District Attorney Matthew Hunter told the jury. “It was untied to any misbehavior.”

Adler testified that the boy had darted away from her in a busy parking lot, and she gave him a spanking through snowpants and another layer of clothing because “she feared that if he did the same action again in the future, he would be in more severe danger.”

Parking lot surveillance footage shows him running away from his mother as the car approaches, then quickly turning toward his mother’s parked truck.

Though other people were around, the only witness was the woman who reported the incident, the same woman who had been driving the car. She testified that she “slowed down a little bit because the little boy was not in the middle of the aisle, but just a little bit in the middle, so I was being cautious.”

After she parked, the woman saw Adler striking her son with a closed fist on the back and butt through her side view mirror, she testified. Adler maintains it was an open-handed spanking. (A DHHS caseworker who viewed the video wrote that she was unable to tell if it was a spanking or not.)

Adler’s attorney asked the jury to “consider how much sense it makes for an individual to use a closed fist to hit someone’s lower back/butt area.”

The prosecutor argued that the video didn’t show Adler react to the car passing the boy, suggesting that she wasn’t afraid he would be hit.

“Do you agree, Ms. Adler, that you didn’t reach for him or try to grab him?” Hunter asked as the court watched the video.

“By the time I could have reached for him, he was already making the turn,” Adler responded.

“You agree you didn’t pick up your pace or pursue him?” Hunter asked.

“Again, by the time I had the fearful response, within one second, he was making that turn,” Adler said.

In her closing arguments, Adler’s lawyer told the jury that “this is a case in which the state is asserting their opinion of Mica’s parenting.”

“Physical discipline of children within reason, again, under Maine law is allowed,” Deveau said. “It doesn’t have to be exactly what you would do as an individual, but what a reasonable parent would do in the same situation.”

The jury deliberated for a little more than an hour. They found Adler not guilty on all counts.

‘Out of our lives’

Once the DHHS case was closed, a parental rights and responsibilities case began between Adler and Santillo over custody of the boy, and Adler’s in-person visits with her son stopped. In February, four months after she had seen him last, an agreement was reached that Adler would have the boy every other weekend.

By then, Adler had a more traditional living situation. She had moved into a modest ranch house with a roommate, who had just become a grandmother. The house was clean and organized, cavernous in comparison to the tiny home.

The visits continued. In May, the parents attended mediation and reached an agreement for the summer: the boy would alternate between the two homes, with Mica getting him for one nine- to ten-day stretch per month.

In mid-June, after driving the five hours roundtrip to pick her son up from a meeting point in Bangor, Adler was watching the now five-year-old boy as he darted through aquatic blasts at Presque Isle’s splash pad, playing at the same park where police found them after the parking lot incident more than a year prior.

She explained that she has essentially abandoned her tiny home, and all it represented — at least for now. She has a job tutoring at the Academic Resource Center at Northern Maine Community College. In the fall, she will begin studying electrical construction and maintenance. It’s possible she’ll eventually get a job working on the grid she once tried to escape.

She is afraid that bringing her son to the small piece of Maine she owns, where she dreamed of raising him, will only invite more trouble.

“If I don’t bring [my son] there, then it’s just going to be easier to keep them out of my life,” she said. “Out of our lives.”

Once school starts, the plan is for Adler to get him every other weekend. But the case is ongoing, and Adler wants more time with the boy.

“I’ll keep trying,” she said, “as long as that’s what he wants.”

Correction: This article was updated to say Mica Adler went to Bangor to pick up her son in mid-June, not to Rumford, and that the current arrangement is for her to get her son for nine or ten days a month.