Editor’s note: This is the first part in a two-part series about the state Pine Tree Development Zones.

Some people call tax breaks for businesses “economic development.”

Others call them “corporate welfare.”

In Maine, one of the names they go by is Pine Tree Development Zones.

The premise of the program is that some businesses won’t create new jobs in Maine unless they get tax breaks.

The program has cost as much as $46 million in lost taxes since 2003, according to Maine Revenue Service estimates. That’s money other taxpayers had to make up to help the state balance its budget.

Proponents of the program say the cost is worth it because without the tax breaks, the businesses never would have created about 8,000 new jobs.

But a Maine Center for Public Interest Reporting investigation has discovered records that reveal the companies that get the tax breaks have never shown that they need them in order to create the jobs – even though the law says they should.

The fact that businesses are given a “bye” on providing evidence they need the tax breaks means there is no certainty that the multi-million-dollar program can be credited with the new jobs.

Economists and others interviewed by the Center called the statement businesses give to show they need the tax break “a fig leaf,” a “farce” and “fictional.”

The official state economist refused to sign off on a section of Pine Tree Development Zones (PTDZ) applications because businesses weren’t required to prove they needed the tax breaks.

And a committee of Maine economists determined that they could not accurately assess the effectiveness of PTDZ because there was no way to correlate the tax breaks to the new jobs.

The Center’s findings are based on a review of thousands of pages of records, including every application to the program, two state-sponsored studies, the legislative history, and interviews with experts.

ZONES A BALDACCI IDEA

The Pine Tree Development Zones were the brainchild of Gov. John Baldacci, who took over as the state’s chief executive in 2003, at a time when the state was losing manufacturing jobs and faced a billion-dollar-deficit.

One of his solutions – offered in his inaugural speech – was the PTDZ.

“In the coming week,” said the Democratic governor, “I will be putting forth a detailed economic strategy. It will include ‘Pine Tree’ opportunity zones to spur economic growth in areas of Maine that really need it …”

Since then, the program has become a key element in the state’s economic development strategy.

Baldacci was following the lead of what other states were doing to compete with growth in the business-friendly Sunbelt.

Pennsylvania and Michigan, for example, had aggressive business incentive programs. They went by different marketing-savvy names, such as Renaissance Zones, and were known generically as enterprise zones. They were designed to attract private investment to distressed areas within a state or a large city. The idea was to lower a business’s expenses, such as taxes, if they created new jobs.

Under the Baldacci administration, more than 300 businesses have been certified for PTDZ tax breaks since 2003. And although Gov. Paul LePage has said nothing publically about the program, his administration approved 37 businesses for the program since 2011, his first year in office.

Although nearly all of the academic studies of enterprise zones show there is little or no evidence they are effective, they have been popular with governors and legislators.

In 2009, the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston convened a panel of experts to debate enterprise zones.

Peter Enrich, a professor at Northeastern University, concluded that the scholarship on business tax breaks should lead government to “Just say no” to them. Taxpayers, he explained, have to pay for the breaks to businesses while there’s no assurance there is a corresponding benefit.

Another panelist had Maine expertise: state Sen. Richard Woodbury, an independent from Yarmouth and a Harvard–trained economist.

As an economist, he said he questions tax break programs because they mean the tax rate has to be higher for everyone else. But as a politician, he said, “If somebody comes to you with a issue, you want to … deal with it.”

In the end, he said, the “political system may overweight” the arguments from the economists.

In Maine’s case, Democrats and Republicans in the Legislature approved Baldacci’s PTDZ in 2003 and also approved expansions of the program in 2006, 2007 and 2009.

‘FICTIONAL’ LETTERS

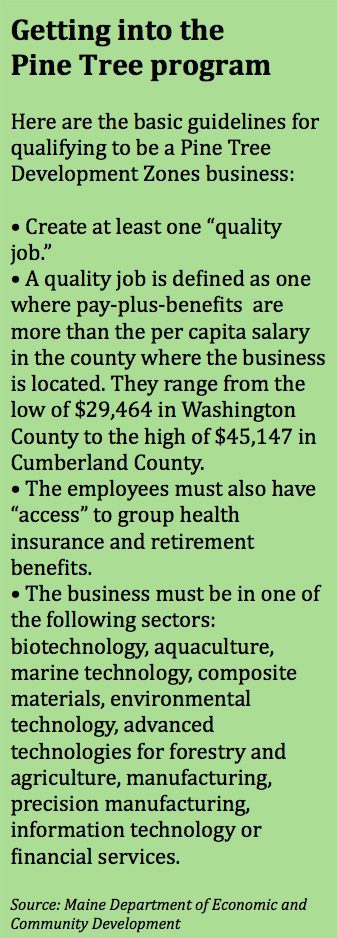

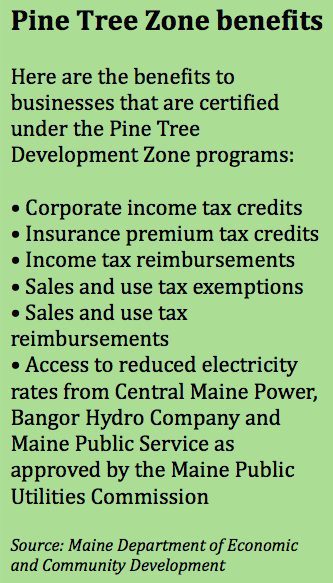

The program works this way: Businesses apply to the state Department of Economic and Community Development (DECD) and promise to create new jobs and make capital investments. In return, they get income and sales taxes breaks and lower electric rates for 10 years in most parts of the state.

Most of the breaks kick in after they have added a minimum of five new jobs. The more jobs they add, the larger the tax breaks.

Businesses must pass a key test to get into the program.

The law that created the PTDZ states that a business can qualify for the program only if “it demonstrates” that without the tax breaks it could not expand or start a news business.

This is known as the “but for” principle.

It means that “but for” the tax break, the business would not add new jobs and make investments in the state.

But never in the eight years of the program has a business been asked for, or even volunteered, any written evidence it needed the tax breaks to start a business or expand, based on the Center’s review of every application in the state’s files.

Instead, the agency that oversees the program, DECD tells the businesses what to say in their application letter in order to meet the “but for” test. DECD directs applicants to copy the following sentence from the sample letter it provides:

“Please be assured that the development project would not occur within the state but for the availability of the Pine Tree Development Zone benefits.”

By including that phrase in their application, the business is seen as meeting the “but for” requirement.

Nearly every letter of the hundreds reviewed by the Center contained that wording, although sometimes the business would fill in its own name.

“The ‘but for’ letter is a fig leaf,” said Charles Colgan, the former state economist, who teaches economic development at the Muskie School of Public Service at the University of Southern Maine.

He was also the chairman of the state’s Consensus Economic Forecasting Commission between 2003 and 2010.

The legislature in 2009 was so concerned about the costs of the PTDZ that it passed a law requiring Colgan’s commission to calculate the tax revenue paid to the state from the new jobs vs. the cost of the tax breaks. The idea was to find out if the program was worth the costs.

The commission — made up of economists and business leaders, all with advanced degrees — wrote on Nov. 1, 2010 to Baldacci and the legislature that they were unable to answer the legislature’s question:

“After considerable deliberations, the (commission) has concluded that we are unable to develop a credible separate forecast” due to the unverifiable assumptions built into the “but for” concept.

They asked that the law that required their analysis of PTDZ be repealed. To date, it has not.

GOVERNOR VS EXPERTS

The discouraging report from the economics experts – two of the five members appointed by the Baldacci administration – did not deter the governor from claiming the program was working.

Less than two months after getting that letter from Colgan’s commission, Baldacci pronounced the program a success.

In December, 2010, with only weeks left in his last term, Baldacci gave a farewell interview to the Maine Insights newsletter, a bimonthly magazine publication.

“As of September, 309 companies have located to Maine or expanded their businesses here because of PTZ incentives,” Baldacci said. “But if not for this program they wouldn’t be here.”

Not only did the state panel of economists have doubts that was the case, but so did the Baldacci administration’s official state economist.

Part of the approval process for being certified for PTDZ was an “advisory opinion” from the state economist.

Michael LeVert held that job from 2007 to 2010.

He said he often declined to check the box on the advisory that stated, “To the best of my knowledge, the proposed business activity will not go through without program financing.”

In effect, this was another way of saying “but for.”

LeVert said that after leaving that box unchecked a number of times, he asked DECD to eliminate that question, and they did.

“I didn’t feel comfortable making that assertion from the information I had. I left it blank most of the time,” he said.

LeVert said Catherine Reilly, who preceded him as state economist, also sometimes left the “but for” clause blank, a fact confirmed by the records and Reilly.

THE GOVERNOR’S RESPONSE

Baldacci is currently the director of military health reform in the Department of Defense (DOD) in Washington. Through his former deputy chief of staff, he told the Center the DOD prohibits him from speaking on “potentially political stories.”

Instead, the former aide, David Farmer, responded to the Center’s questions.

“Measuring the effectiveness of economic development programs is difficult, but it’s much easier to see what happens when a state, competing for new jobs, can’t offer an aggressive policy. The jobs go elsewhere,” Farmer wrote in an email response to the Center’s questions.

“Pine Tree Zones have helped to create thousands of good-paying jobs with benefits and led to hundreds of millions of dollars worth of investment in our state. It’s better to invest resources to create good jobs, which Pine Tree Zones require, than it is to spend that money to address the consequences of more people being out of work.”

Baldacci’s confidence in the program is confirmed by some business owners, such as the vice president of Rumery’s Boatyard in Biddeford, a certified PTDZ business. Sean Tarpey told the Portland Press Herald in 2006 that the PTDZ benefits made it easier to “go out on a limb and hire people and pay a good wage and hope the business will expand the way we want.”

One of the jewels in the PTDZ program has been T-Mobile, which announced in 2004 it would open a call center with 700 jobs in Oakland. Baldacci has said the PTDZ program was key to bringing T-Mobile to Oakland. However, at one of the official events surrounding the opening, Maine Public Broadcasting reported that when T-Mobile Vice President John Birrer was asked about the PTDZ benefits, he said, “We would have come here without the incentives.”

One of the few legislators to object to the PTDZ from the beginning was Peter Mills, the Republican from Cornville and currently the executive director of the Maine Turnpike Authority.

He said that one of the purposes of the “but for” requirement was to “empower the administration to claim that the ensuing jobs were actually created by a tax concession – as if to say that tax law manipulations alone could create such opportunities. That was largely fictional …”

But state Rep. Christopher Rector, R-Thomaston, believes the program has been successful, at least in his district.

“While the benefits can be substantial to the businesses, the benefits in employment in our region here in the midcoast have also been substantial. Both Boston Financial and Athena Health are examples of the recruitment power of the Pine Tree Zone benefits. They have said it would not have been the first location choice for their operations were those benefits not in place.”

The signed advisory opinion from the state economist in Boston Financials’ PTDZ file leaves blank the question of whether the businesses would have been opened without PTDZ tax breaks. The Athena file did not contain an advisory opinion.

Maine & Co. is a non-profit that helps recruit new businesses. Peter DelGreco, the president and CEO, said PTDZ are an essential recruiting tool.

“I know first hand that there are companies that would not be here but for the existence of those programs,” he said, although confidentiality rules prohibited him from naming the companies.

George Gervais has been commissioner of DECD less than a year, but has been in the department since 2008 at lower positions.

Whether the “but for” letters are window-dressing “is a hard question to answer,” he said. When he came into the agency, Gervais said he was trained that a company met the “but for” test if their decision to locate in Maine vs. another state was dependent on the PTDZ tax breaks.

He said he could understand why the ‘but for’ language is viewed with “skepticism.”

“There are companies who are very comfortable saying that, when it may not be true. How do you prove that?”

On the one hand, Gervais said, he recalled businesses that decided not to apply for the PTDZ because they felt “they could move forward without the program.”

Former state Rep. Nancy Smith, D-Monmouth and former co-chair of the legislature’s economic development committee supported PTDZ when she was in the House. As for the “but for” requirement, she said, “Get rid of it. It’s a farce. It doesn’t pass the straight face test. That’s not to say incentives for businesses don’t have value.”

Why are governments so enamored of tax incentive programs — Maine has a total of 46 — when there is so much skepticism from economists?

Colgan, the Muskie School economist who has been involved with Maine government for decades, has an explanation:

“Let’s just say that enterprise zones are some people’s ideas of what government ought to do,” he said. “Since it fits those ideas, then they think, it must be a good idea.”

This story has been updated to clarify the description of the publication, Maine Insights.

To read the second part of this series click here.