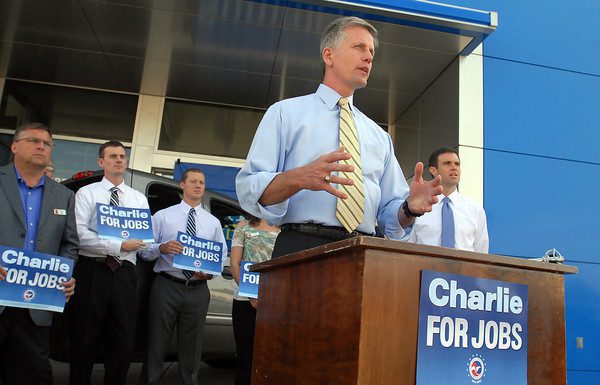

Republican Charlie Summers has pinned his campaign for the U.S. Senate on a vow to improve the economy and create jobs on a national level the way he says he has on the state level.

As Maine’s secretary of state, Summers added a $50,000 “Small Business Advocate” in his office that he says on his campaign website shows how “investing in small businesses will create jobs and strengthen our economy.”

If elected, Summers states he will “introduce legislation that will create a national small business advocate, just like the one I successfully lobbied for in Maine who has already saved Maine businesses from undue state regulators.”

But a Maine Center for Public Interest Reporting examination of the business advocate’s own records tells a much more mixed story of the effectiveness of the new position that was filled last October by Jay Martin of Old Town.

While Summers boasts the program is a job creator, in the 10 months the advocate has been on the job, records show few, if any, new jobs can be directly attributed to the work of the business advocate.

For seven weeks this spring and summer, from June 1 to July 27, the advocate did not have a single open case, according to weekly activity reports.

The records also reveal that the advocate claims credit for solving problems that others solved, suffers from legal restrictions that handicap his effectiveness and did not meet two of the six minimum requirements for the job.

Dan Billings, chief legal counsel to Gov. Paul LePage, was critical of the position on As Maine Goes, the popular web forum for Maine Republicans: “My point is that someone should look at whether the Small Business Advocate is actually making a difference or just taking credit for cases that were on the way to resolution anyway,” he wrote on May 13.

Responding to the Center’s findings, Summers said, “We’ve met with some early successes in this but I think to actually quantify, in the longer term you’ll need a few years of data. Do I think it’s a success, do I think it’s a success that the state government now has a position of someone who can act independently of the executive. Yeah, I think that’s a success.”

One of Summers’ opponents in the June GOP Senate primary noted the contradiction of a limited-government candidate expanding his own government agency.

On his campaign Facebook page, Rick Bennett, former president of the Maine Senate, noted “the irony of trying to solve a problem created by government with more government.” The comment is posted next to a photo of Martin wearing a Summers campaign button and handing out Summers campaign literature at a weekend candidate forum in Trenton.

Summers was sworn into office in January, 2011, shortly after the Republican sweep of the statehouse in 2010. His position is a constitutional office elected by the legislature.

His election followed two terms in the state senate, nine years as Sen. Olympia Snowe’s state director, a stint as the region’s Small Business Administration head, and three failed campaigns for Congress. He is a member of the U. S. Navy Reserve and served in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Summers, Democrat Cynthia Dill and independent Angus King are running for Snowe’s open seat.

Once in the Secretary of State’s office, Summers proposed the establishment of the small business advocate to “assist businesses when established agency procedures fail to resolve problems or disputes,” as he told a legislative committee.

A scaled-back version of Summers’ proposal passed and in October, 2011, he appointed Martin as the first small business advocate. Martin started work on Oct. 6, 2011.

Previously, Martin ran his own consulting firm, Write It Right, where he helped businesses write grant applications and proposals and performed other related services.

Martin says his office has received 117 cases and has “closed” 22 of them. Three cases are what he called “pending,” while 41 were referred on to other departments, 37 never opened and 14 deemed “outside scope” of the office.

Martin’s work spans a range of actions from referral to other agencies to writing letters to actively advocating before agencies himself. The cases range from a drug store fighting a fine over an unlicensed pharmacist to a Portland business battling with regulators about its wastewater discharges.

The record reveals that Martin typically asks businesses to fill out an intake form, then does preliminary research into the problem, talks to regulators in relevant departments and reviews relevant laws.

If he decides to go further with a case, Martin goes to bat for business owners by requesting a range of actions from other state agencies: fines lowered, sanctions eliminated, licenses granted or restored. In several cases, Martin urged a department to exercise “discretion” and limit the severity of a sanction or eliminate it altogether.

Four seasonal jobs retained

Some business owners have praised Martin’s work, including developers of a disc golf course.

“Jay most certainly put 100% of his effort into helping us save the Disc golf course from being closed down by the DEP,” wrote Dr. James LaVallee and Ron LaVallee, owners of LaVallee Links in Randolph.

The LaVallees had been involved in a conflict with the state over environmental construction violations at their newly built course. Resolving the conflict, wrote Martin in a report, meant “4 seasonal jobs retained.”

Another case involved a Bath drug store facing almost $500,000 in repayment of Medicaid fees to the state Department of Health and Human Services because a pharmacist had been practicing without a current license for three years. The drugstore owner said he would have to close or sell if forced to pay, resulting in the loss of 16 year-round jobs and 25 seasonal ones.

Martin joined the Wilson’s Drug Store’s attorney in requesting a lower repayment amount which Martin wrote was “unreasonable and unfair.” Ultimately, the amount was lowered to $25,700 and the drugstore remained open, leading Martin to claim, “the Advocate negotiated an equitable resolution between the owner and state agency.”

Herbert Downs, director of audit for DHHS, disputed Martin’s claim that he negotiated the settlement.

“No, that would not be true at all,” said Downs.

Downs said Martin “sat in on the meeting” and “commented,” but the negotiation was among the pharmacist’s attorney, Downs and a DHHS staffer.

“Without question,” responded Summers, “had the Small Business Advocate not been put into statute by the legislature and signed by the governor, these individuals would have had a much different reception.”

After discussing the pharmacy case, Summers could cite only one more example of the advocate’s success, needing to be prompted by Martin.

“I know that there are others, there are, I think, well, there’s the golf …” said Summers, trailing off.

“And, specifically, the coffee company,” added Martin.

The coffee company was Portland business Kerry Ingredients and Flavors, the Maine outpost of the multinational flavorings giant Kerry Group. Martin’s own records in that case demonstrate the difficulty in crediting the advocate with settling disputes and creating jobs.

The city of Portland, citing Department of Environmental Protection regulations, wanted Kerry to install a system to separate roof drainage from its wastewater; the company wanted to take a less costly route.

Martin attended a decisive meeting on Feb. 3, 2012 with company and state and local officials. In a Feb. 9, 2012 email to Portland state Rep. Peter Stuckey, Martin wrote that the problem had been resolved and that Kerry would be able to use a less expensive option for handling its wastewater.

“I understand that Kerry now may move ahead with its expansion plans, possibly creating as many as 20 new manufacturing jobs,” wrote Martin. “Though I played a minor role in resolving this issue, I am pleased that this group achieved an equitable resolution to a legitimate regulatory enforcement grievance.”

Yet, in a report dated only two weeks later, Martin claims a larger role and has a new jobs number: “The Advocate negotiated an equitable resolution between the manager and state agency. … Business is now able to move ahead with expansion plans that will likely create 10 full-time manufacturing jobs.”

But Martin’s claim of a “likely” 10 jobs was made after an email exchange in which a Kerry official is vague about the number of jobs.

In a Feb. 16, 2010 email to Kerry employee Christopher Thiel, Martin asked, “I recall you describing your expansion plans as creating up to 20 jobs. Is that correct?”

Thiel responded, “not sure on the quantity, but we have potential business that we are working on that could increase our volume by 30-50%, which will result in a transposable figure of jobs for people.”

Kerry spokeswoman Teresa Polli told the Center that the Portland facility had the “same head count since February” and had not expanded.

Martin responded to that news by saying that he had not actually claimed jobs would be created, only that they might be.

Summers conceded that by creating the advocate’s position, he had not created jobs.

“I don’t think government creates jobs,” said Summers. “But I do think that the atmosphere that we create has an effect on whether or not a business is willing to come to the state of Maine, or invest in the state of Maine or grow in the state of Maine.

“That business knows that, if there is truly a problem they can come to our office and they will have a very open and unbiased ear to tell their story to and if we can be of help, and in a number of occasions over the last ten months we have been able to be of help.”

Barred from meeting

Martin’s effectiveness has been hampered by laws and regulations that prevent him from gaining access to certain agency records or proceedings.

In the case of Great Falls Builders, Inc., the Gorham construction company was in a conflict with the state’s Unemployment Insurance Commission over whether certain construction workers were employees or subcontractors, a distinction that could cost the company a lot of money.

Martin proposed to join Great Falls president Jon Smith at a hearing before the commission. In a note to the case file, Martin wrote that the chair of the commission “politely said that I am not allowed to attend due to the confidential nature of information shared at that meeting. I asked her to reconsider but she said her decision was firm.”

The file note says, “Mr. Smith ultimately lost his appeal to the UIC. Case closed.”

In an interview last week, Billings, who supported Rick Bennett in the Republican senatorial primary, was less critical about the position: “It’s still pretty early on in the process to make a judgment,” he said. “At the end of the day, I think we’re all in agreement to have someone located somewhere to help people work through the minefield of state regulations and bring some pressure to bear when an agency isn’t acting appropriately.”

When the advocate’s job was created, there were six minimum qualifications. Martin’s resume showed that he met four of those qualifications. But there are two that he did not, according to his resume. Those two were knowledge of the state Administrative Procedure Act (APA), which both outlines and limits the actions and procedures that state agencies can take; and a “knowledge of the legislative process.”

In his weekly activity report to Summers dated Nov. 1, 2011, Martin lists “Ongoing review of APA” as one of his activities.

Summers defended his choice of Martin.

“I think that Jay has enough knowledge of the legislature and the legislative process and if I feel in my judgment that someone is qualified and can in some cases grow into the position in terms of the actual legislative interaction, then that is at my discretion,” he said.

Testifying in February 2011 to a legislative committee about the small business advocate’s duties, Summers said, “I believe they can be effectively executed within the existing resources of the Secretary of State’s Office.”

In fact, the position in the budget that Martin eventually took had been frozen until 2011. When it was “unfrozen,” Summers had the option of filling it or leaving it vacant. He chose to fill it with the advocate position at a cost to taxpayers of $80,000-$84,000 for salary and benefits.

Was the addition of the position a contradiction of Summers’ stated goal of “cutting government?”

“No,” said Summers. “The position already existed and chances are it would have been filled” by naming a new assistant secretary of state.

Finally, it’s not clear there’s even enough work for the Secretary of State’s Small Business Advocate to do. Martin’s activity reports between the weeks of June 1 and July 27, 2012 report that during that time, there have been no “open” cases.

Summers says he’s not concerned about that.

“No, I’d say that ‘s probably a good thing, because either it is reflective of the fact that there is a different environment in Augusta and businesses are not either suffering the same fate as they had earlier, or Jay has done his job very very well,” said Summers.

“I don’t think that the fact that a few weeks have gone by and considering the fact that the legislature is out of session and many of the cases came to my attention through legislators, then I think that a seven or eight week period is not anything to be concerned about.”

Watch the Center’s edited Interview with Charlie Summers

Watch the Center’s full, 20 minute interview with Charlie Summers

CORRECTION: An earlier version of this story stated that Summers had run for governor in 2010. He did not.