Shortly after hearing from the Maine Department of Environmental Protection that their well should be tested for per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), a Fairfield couple watched the movie “Erin Brockovich,” a true-life legal drama set in the 1990s. Julia Roberts portrays a struggling single mother of three young children who, in her newfound work as a legal aide, uncovers evidence that a Pacific Gas and Electric plant in Hinkley, Calif., was poisoning the community’s water source, prompting a successful lawsuit against the corporation.

Following the movie, the couple wondered, “What if that happens here? What if this is us?”

By early 2021, Brockovich, who became a community health advocate, had begun to work with Fairfield-area residents, mobilizing a legal team and water experts.

The Maine Legislature subsequently took a critical step to ensure that legal actions would not be hampered by these chemicals having been in the environment for decades. In June 2021, Gov. Janet Mills signed a law clarifying that Maine’s six-year statute of limitations applies to the time of PFAS discovery rather than its initial occurrence on a property.

The statute of limitations is one of many complicating factors in legal cases involving toxic chemicals, where extensive time can elapse between initial exposure and evidence of medical harm. PFAS pose particular challenges even relative to compounds like asbestos and mercury because so much about them remains unknown.

While PFAS are often labeled “emerging contaminants,” it’s the scientific and toxicological understanding of them that’s emerging, not the compounds themselves. They have been produced since the 1950s and manufacturers knew of their dangers a half-century ago.

‘An explosion of litigation’

Evidence of early corporate awareness about the chemicals’ toxicity came largely from cases brought by Ohio attorney Robert Bilott, a partner at Taft Stettinius & Hollister LLP. His 22-year legal battle with DuPont, captured in the movie “Dark Waters” and his book “Exposure,” has secured more than $1 billion for PFAS-affected clients.

Bilott’s first PFAS suit, settled in 2001, unearthed more than 110,000 pages of evidence that he synthesized into a 978-page public letter shared in 2001 with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

A subsequent settlement in 2004 required DuPont to fund an independent scientific panel assessing links between PFAS exposure and medical conditions in roughly 70,000 people whose drinking water was contaminated with PFAS from one of the chemical company’s manufacturing plants. That seven-year study helped link PFAS exposure to medical conditions such as ulcerative colitis, thyroid disease, and testicular and kidney cancer.

Now Bilott is seeking a broader-scale scientific panel to assess medical impacts in a class action suit filed in 2018 in U.S. District Court Southern District of Ohio that could include tens of millions of U.S. citizens with PFAS in their blood (according to CDC research, that applies to nearly every American). The panel would look at potential health damage from multiple PFAS, including the second-generation (GenX) chemicals that manufacturers began producing when pressured to stop making ‘legacy’ (or long-chain) PFAS compounds. “They can’t bring out new PFAS chemicals and then say there’s insufficient evidence as to whether they’re harmful or not,” Bilott said.

It’s not clear whether residents of other states will be included with the more than 10 million represented in Ohio. “In coming months,” Bilott added, “the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals will be taking briefs about whether the case can proceed on behalf of such a class.”

That suit might only be open to residents of states that recognize medical monitoring as a legal claim. In toxic tort cases, plaintiffs often claim a need for medical monitoring, such as annual blood work or other periodic tests, to aid in early detection of diseases related to their chemical exposures. While 16 states recognize medical monitoring to some extent, a 2020 summary in Vermont Law Review by Megan Noonan noted that Maine does not do so explicitly and past cases make its treatment unclear.

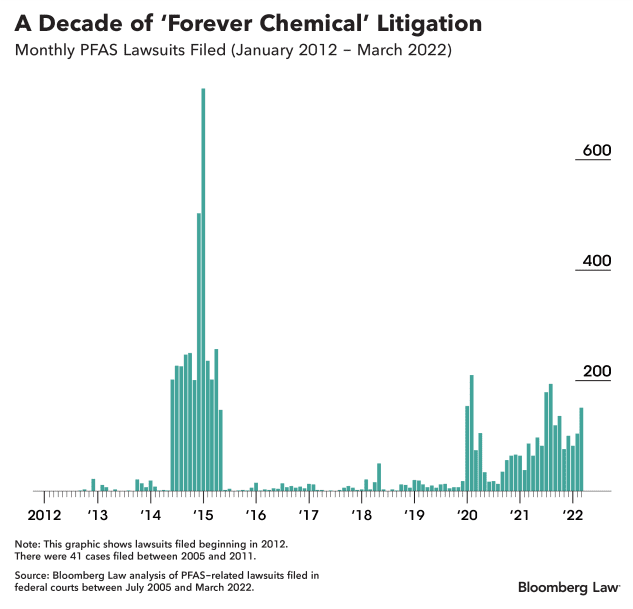

In recent years, awareness “has grown markedly that these compounds are not only a national problem but a global one,” Bilott said. Now there’s “an explosion of litigation” not only among states but among municipalities, water providers and affected citizens.

Utilities that treat wastewater from sources that use PFAS recognized early on that they could become “prime targets” for litigation and their rate payers could be left bearing the costs of filtering out those chemicals, said John Gardella, a trial attorney and shareholder at CMBG3 Law in Boston who often writes about PFAS litigation in The National Law Review. Water utilities “have actually gone on the offensive, filing suits largely against the chemical manufacturers, (arguing that) they were not told by the chemical manufacturers about these chemicals and had no way to filter them out.”

In Maine, a lawsuit involving 13 plaintiffs, all residents of Fairfield, filed in 2021 by attorneys working with Brockovich seeks damages from paper companies and chemical manufacturing corporations for the costs of property and water remediation, harm to immune systems and mental anguish, among other injuries.

The regulatory roadmap is clear, the litigation one less so

A national trend toward stricter PFAS regulations will influence litigation, Gardella said, because “plaintiffs will point to the evolution of those regulations,” and draw on legislative hearings and records.

While Maine is at the forefront of states setting PFAS regulations, about 15 other states have already moved to take legal action, largely against PFAS manufacturers. Last month California announced a sweeping suit against chemical manufacturers, claiming they “created and/or contributed to a public nuisance, harmed and destroyed natural resources, marketed defective products, failed to provide adequate warnings concerning the use of their products, and engaged in unlawful business practices.” The suit seeks statewide relief for drinking water treatment, water replacement, medical monitoring, environmental testing and PFAS disposal.

States often hire one or more outside law firms to help develop and implement legal strategy concerning PFAS. Firms typically work on a contingency fee, charging governmental entities less than the 30 to 40 percent trial attorneys often charge in private suits, although arrangements vary markedly in rates and structuring among firms. Suits involving toxic contaminants can be costly, often requiring extensive discovery and testimony by paid expert witnesses.

In October 2021, the Office of the Maine Attorney General received proposals from law firms to assist the state in recovering PFAS damages. Attorney General Aaron Frey said last June on a Maine Public radio program that “in the very near future” people could expect an announcement because the office was “close to locking up the outside counsel.” There has been no further word.

‘Broad authority to represent the public interest’

The AG’s office anticipates working with staff and a team of outside counsel on a strategy to address the state’s damages, according to Scott Boak, who heads the office’s natural resources division. It is considering options that could include multiple lawsuits involving different types of PFAS.

Some states, for example, have filed complaints related to AFFF (firefighting foam) separately from other types of PFAS. Typically, state lawsuits involving AFFF are transferred to federal court and become part of what’s known as “federal multidistrict litigation,” which consolidates similar cases for greater efficiency. More than 2,500 cases related to AFFF exposure and environmental contamination are already amassed in the U.S. District Court of South Carolina.

Filing a suit or multiple suits is “certainly an option,” Boak said, “but at this stage our office hasn’t made any decisions yet about how the state will proceed.” Alternatively, the AG’s office could opt for what he termed a “pre-suit resolution,” negotiating a settlement with the help of outside counsel.

Tribal communities within Maine face serious concerns with PFAS contamination, but to date the AG’s office has not engaged tribal leaders in the legal planning.

The strategy chosen by the AG’s office could have far-reaching impacts for Maine residents. Contending with Maine’s PFAS-contaminated soils, waters and food systems has already cost an estimated $200 million, with future expenses potentially running many times that.

RELATED: The price of PFAS: ‘Forever chemicals generate boundless costs’

In one of the few state suits that has been resolved, Minnesota sought $5 billion for water contamination and settled for $850 million. It’s typical for funds received to be far lower than the initial request, Gardella said.

Delaware chose not to pursue litigation and in 2021 reached a “settlement agreement, limited release, waiver and covenant not to sue” with DuPont and three spinoff corporations in which the people of Delaware received $50 million from the corporations for a Natural Resources and Sustainability Trust Fund to help with environmental projects. The state could receive up to another $25 million each time within an eight-year period that corporations settle with other states for higher amounts.

In Maine, decisions concerning PFAS actions or settlements are “encompassed within the AG’s broad authority to represent the public interest and prosecute claims for damages on behalf of the state,” noted Danna Hayes, special assistant to the AG. Regardless of strategy, Gardella said, states have to clearly define “the true scope of the damages” and “have to actually prove the numbers.”

Across the nation, there’s growing pressure to address this vast class of chemicals that has gone largely unregulated for more than half a century. Public awareness is sparking more policy discussion, but it’s also driving “a lot of what is going on [with PFAS litigation] in this country,” Gardella said, a trend he finds unique to PFAS since often public awareness follows lawsuits rather than preceding them.

Reports about PFAS in Maine and its response are a part of that transformation, in Bilott’s view. “Getting that story out is leading to people speaking out,” he said, a trend now evident across the country. “We’re seeing laws and regulations starting to change, which shows the power of making information available to people about a public health threat.”

This project was produced with support from the Doris O’Donnell Innovations in Investigative Journalism Fellowship, awarded by the Center for Media Innovation at Point Park University in Pittsburgh, Pa.