Editor’s Note: The following story first appeared in The Maine Monitor’s free environmental newsletter, Climate Monitor, that is delivered to inboxes for every Friday morning. Sign up for the free newsletter to get important environmental news by registering at this link.

First, to those I haven’t yet (virtually) met, hello from the haze of (yay) new parenthood and (ugh) COVID, and thank you to the fantastic Annie Ropeik, who has been keeping you all informed while I’ve been on maternity leave. Don’t worry, you’ll be hearing from her again soon, as we’ll be trading off writing the Climate Monitor for awhile while I get back into the swing of things.

As someone who now does approximately 273 loads of laundry and dishes each week, I’m more aware than ever of my water use — as I write, I can hear the long whoosh of the washing machine as it scrubs the spit up out of my daughter’s onesies. Water was also on my mind yesterday, as I tuned in to the final meeting of the Commission To Study the Role of Water As a Resource in the State of Maine.

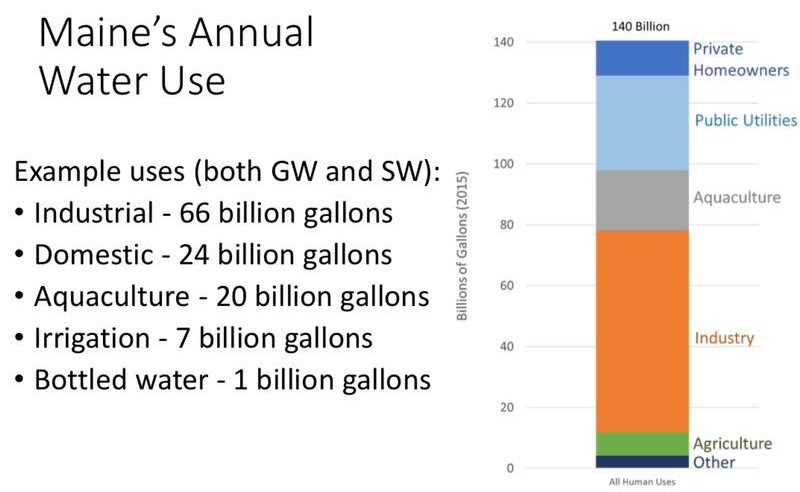

The 16-member Commission, which arose out of a bill to tax bottled water exports, met five times before issuing its draft report yesterday. It had an expansive mandate, including studying the extent of the state’s resources as well as the legal principles regarding ownership, the state’s future water needs, exportation of water and sustainability of aquifers, among other issues.

That’s a lot to accomplish over the course of five meetings, so perhaps it’ll come as no surprise that the commission’s topline recommendation was to establish a new, “more focused” commission to address the old commission’s “unresolved work.”

“We have a lot of work to do,” said Nickie Sekera, a Fryeburg resident and commission member representing the public, who said she felt five meetings simply was not enough time to accomplish the group’s mandate. “It feels so rushed and so incomplete… but you have to start somewhere.”

Members included activists such as Sekera as well as representatives of state agencies and the bottling giant Poland Spring, which has operated in Maine since 1845 and is now owned by a pair of private equity firms. Conflicts between bottlers and activists have bubbled for decades, particularly in the western area of the state, where Poland Spring is most active.

Not everyone was excited by the prospect of a new commission. “The current regime works extremely well, and has for decades,” said Bruce Berger, executive director of Maine Water Utilities Association. “The issues here in this state aren’t the issues in other states… In the West you have 12 straws and one cup, here you have 12 cups that each have a straw. That’s the difference in the hydrology between New England and other places.”

Others worried that a new commission would be duplicating the work of the Water Resources Planning Committee, which met most recently this past April.

Ryan Gordon, Hydrogeologist at the Maine Geological Survey, said that while he was “in general very supportive” of the recommendations, several colleagues who’d read the draft were “dubious” of the need for a new commission and worried that it would be “redundant to the work that’s already being done” by the Water Resources Planning Committee and others.

A recommendation to further study the legal status of groundwater rights and ownership in Maine also met with some pushback from both Berger and Mark Dubois, Natural Resource Manager with Nestle Waters.

In Maine, groundwater is the property of the landowner, who is “not liable for damages if their use of that groundwater affects a neighbor’s or adjacent user’s ability to access the groundwater below their property,” according to the draft report, what is known as “absolute dominion.”

That worries some activists, including Sekera, who would like to see groundwater held in the public trust, which they say would protect Maine’s resources from privatization and allow for better long-range planning. “It’s important to disrupt Wall Street’s grab on our water,” she said in an interview before the meeting. “You kind of have to imagine the future, when water isn’t running freely.”

But Berger said that changing the law would impact public water suppliers, who “need to know that the supply is ours and it’s available to use.” He also noted that there are many exceptions to the absolute dominion rule, which has been modified over the years.

“Maine does not allow unfettered water extraction based solely on land ownership,” said Berger. “It’s regulated by several different agencies. Even though the land is mine and I have rights to the groundwater, I have no rights to arbitrarily extract the amount of water under my property.”

A recommendation that the Legislature consider requiring commercial bottlers to test for and report on PFAS levels was less controversial, with all commission members who were present voting in favor.

The commission also recommended taking steps to centralize data on water use within a single state agency, collect more data, require annual reporting to the Legislature on water use and asked that state agencies identify measures to enhance drought preparedness and drought resilience by agricultural producers. It also suggested making data on water use more available to the public.

The final report is due out Dec. 7; it will be sent to the Legislature and will eventually be taken up by the Taxation Committee, which will determine whether they want to take any action on the report’s recommendations. In the meantime, you can watch all of the commission’s meetings and its materials here.

To read the full edition of this newsletter, see Climate Monitor: Water commission recommends another commission.

Kate Cough covers the environment for The Maine Monitor. Reach her with story ideas by email: gro.r1757823800otino1757823800menia1757823800meht@1757823800etak1757823800.