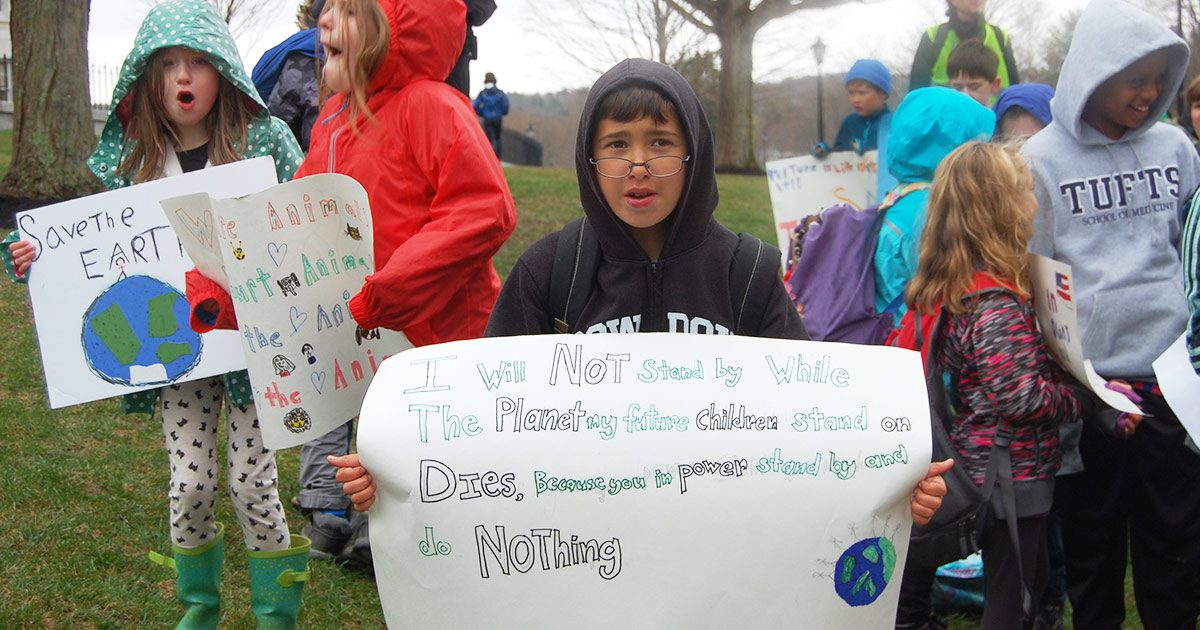

AUGUSTA — A raw north wind and showers did not keep several hundred students from gathering at the Maine Youth Day of Action rally on Tuesday, standing resolutely outside the Statehouse with handmade signs and voicing demands for climate justice.

The rally was timed to coincide with a committee hearing on LD 1282, a Green New Deal bill that aims to accelerate Maine’s transition to renewable energy in ways that foster equity and economic opportunities for the state’s residents.

After listening to speakers that included fellow students, U.S. Rep. Chellie Pingree (D-Maine) and Gov. Janet Mills, many students stayed on to meet with legislators and testify on the GND bill. As students from elementary school through college sat waiting in the Statehouse and Burton Cross Building, I spoke with more than a dozen of them to hear what had brought them to Augusta.

Several talked about their love for nature – “the most beautiful things on earth are in the natural world” – and their passion for animals – “I cry about the polar bear thing.”

“Ever since I was little, the ocean was one of my favorite things” said Vi Walsh, 11, a student at Friends School in Cumberland. But with climate change, “all those species I care about – the fish, porpoises, squid – will be gone.”

Mae Causey, 17, a Falmouth High School student, has witnessed environmental threats to resources in her home state of Alaska, including an open-pit mine being proposed near one of that state’s biggest salmon-spawning grounds. As young people, she said, “We want a future. We don’t want to lose that to rising temperatures and rising waters.”

College of the Atlantic student Iris Fen Gillingham, 19, grew up on a New York farm that experienced – in the span of five years – two 100-year floods and one 500-year flood. She said her childhood, living on land above Marcellus shale, was marked by the “looming threat of fracking.”

A sense of urgency propels these young people to action. “Every day,” an 11-year-old confessed, “I’m scared I’ll wake up and it will be too late to fix things.”

In lives that only stretch a decade or two, these students already have witnessed the effects of climate change. Many of them commented on increasingly erratic weather patterns they described as “crazy,” “wonky” or simply “off.” They’ve seen growing seasons lengthen, ski seasons shorten and explosive growth in the population of deer ticks. One 12-year-old noted that she has already dealt with three cases of Lyme disease.

They view the environmental challenges posed by climate change as inextricably fused to economic and racial justice. Josh Caldwell, a 21-year-old Bates College senior who works as a Maine People’s Alliance organizer, said he came to realize that climate disruptions would have a “disproportionate impact on certain populations – youth, marginalized communities and low-income people.”

Several students acknowledged that travel opened their eyes to how bad environmental degradation like smog, litter and water pollution can get in settings with more people and fewer resources. Westbrook High School student Sadie Cross, 17, said a trip to Guatemala helped her see how many people cannot “escape environmental injustices” and “don’t have a voice or platform” for change.

People who do have that opportunity need to exercise it, Cross believes. She hopes other young people in Maine will “watch and absorb as much as you can, educate yourself, and then have a voice and make sure you vote.”

Students knowledgeable about environmental science like 17-year-old Scarborough High School senior Ryan O’Leary find it “concerning to have federal leaders not recognizing that.”

Young people also are disturbed by the shameless partisanship – on both sides – that marks climate discussions. Several noted misgivings over a rally speaker’s mention of “leaning left,” for example. “It’s not about bringing people left,” nor is it a “Democratic issue,” noted Yarmouth High School student Juliette Edmond: “The world is everyone’s problem.”

“Climate change doesn’t have a political party. Why does it have to be divided like that?!” asked Ava Gleason of Scarborough High School.

Laura Morris, a 15-year-old from Portland’s Baxter Academy, said she “feels really strongly that climate change is not an issue that should be divided between parties. There should be some things politics needs to step away from.” It’s the “responsibility of our government to protect us,” but the government is not fulfilling that role, she said.

To overcome that failure, 11-year old Mira Hartmann of the Friends School said leaders will need to start by “accepting that we have a problem and actually doing something about it.”

Students see the Maine GND bill as a “really crucial step,” noted Caldwell – “one that relies on the insights of Maine people.”

“Maine can lead the way on this, demonstrating it’s actually possible,” observes Bowdoin College student Perrin Milliken, 19, to take “bold action that doesn’t harm the economy.” She found herself shifting this past year from experiencing a sense of frustration and futility to recognizing the need for collective action. “We all have to be fighting for this if we want something to happen.”

It was striking to hear these adolescents already looking out for those even younger than themselves. Two actually referenced the “younger generation” coming up behind them as if they themselves were no longer young. Edmond, at 15, spoke of her concern for her baby sister, Luna: “I don’t want her living in a world that is dying.”

Why, I wonder, don’t more adults share that concern for the world these young people are inheriting? Fifteen-year-old Gleason put it well: “It’s heartbreaking that kids are dealing with this because adults aren’t.”