The infants arrive at the hospital with broken legs and arms.

Sometimes their ribs are fractured.

Others undergo CT scans and tests that show bleeding in their brain and behind their eyes – telltale signs that the babies have been violently shaken.

Dr. Amanda Brownell, Maine’s sole pediatric child abuse expert, examines each of her patients carefully to determine whether the bruises, broken bones or brain damage are the result of an accident, illness or abuse.

Over the past few months, Brownell evaluated three babies who were shaken and suffered brain damage. “Fatalities are unfortunately the tip of the tragic iceberg of abuse in this state,” she said.

While child homicides spark investigations and outrage, they represent a small percent of the abuse and neglect that occur throughout Maine.

“We see all those tragedies and fatalities in the news,” said Brownell. “But we also have to be conscious of the fact there are many children who are injured and survive, often with long-term consequences that can be quite severe.”

With head trauma, babies and children can suffer mild learning disabilities to devastating neurological complications, Brownell said.

“They can suffer blindness or the inability to walk or talk,” she said. “They sometimes rely on feeding tubes or need a tracheostomy to breathe.”

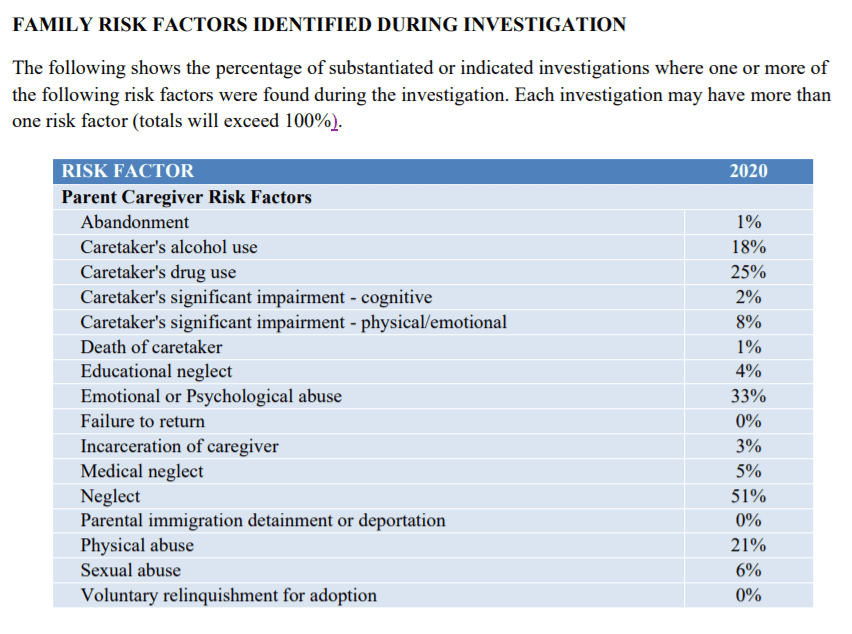

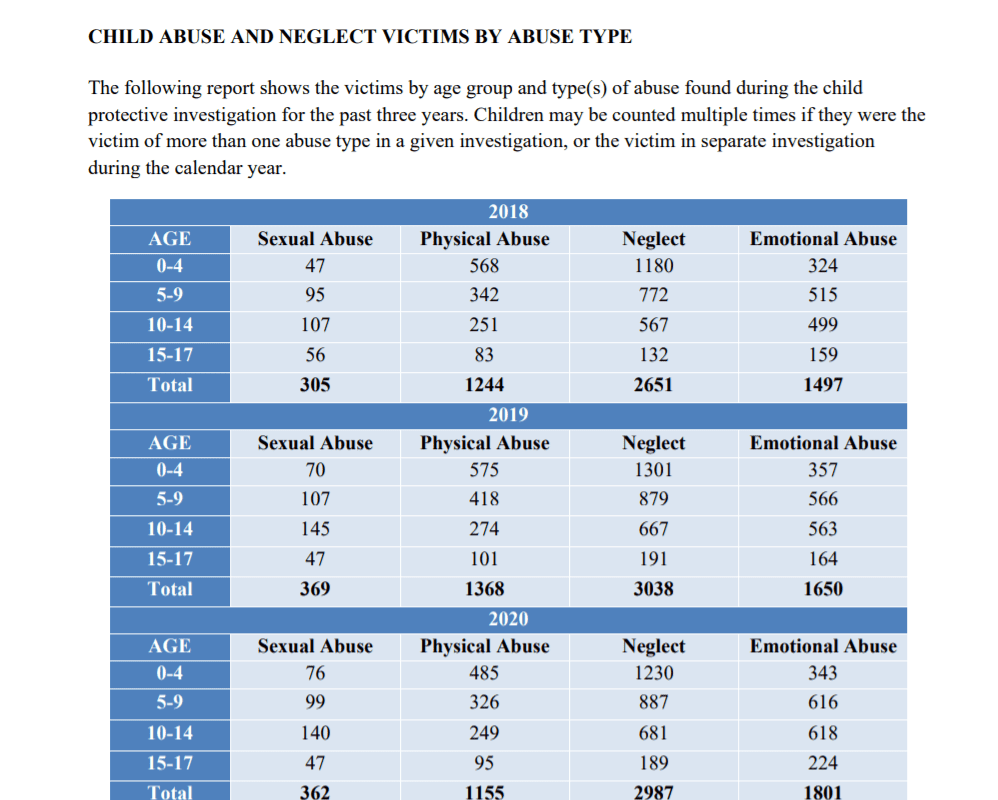

In 2020, state child protective caseworkers investigated 10,613 reports of abuse and neglect involving 13,731 children. They found maltreatment in less than a third of those reports, or 2,994 cases. The other 7,619 cases were deemed unsubstantiated, meaning case workers did not find enough evidence of abuse or neglect.

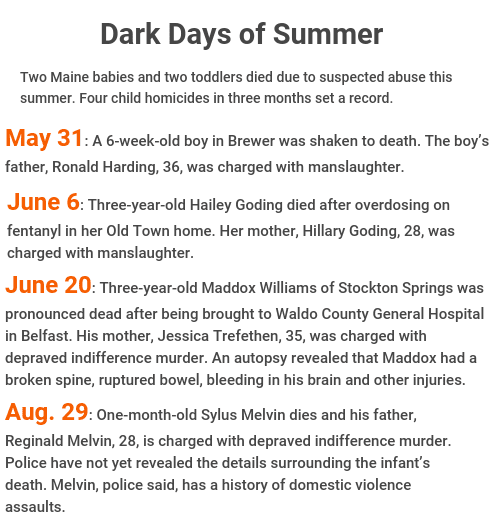

This summer, a record high of four Maine children died in unsafe homes. A toddler was beaten to death. A baby was shaken to death and another infant died from injuries that have not been released. A 3-year-old died ingesting fentanyl in her home. The deaths reignited scrutiny over the state’s child protective services, which were involved with most of the families before the deaths. A top concern, child advocates say, is the lack of thorough investigations to determine whether children are in jeopardy in their homes.

RELATED: Diagnosing abuse requires collaboration and expert advice, child advocates say

Abuse detection a complex process

Assessments in suspected abuse and neglect cases, Brownell said, are often complicated, and require detailed and multiple evaluations of both the child and its parents or caretakers.

As medical director for the Spurwink Center for Safe and Healthy Families in South Portland, Brownell and her nurse practitioner evaluate about 1,000 babies and children a year to determine whether they have been abused or neglected. Roughly half of those cases are substantiated, Brownell said, which represents only a small portion of the children in the state who are injured.

“I am usually called in the beginning when it’s unclear what’s happening with the child,” said Brownell. “I become involved with what kind of test should be done or what kind of labs or images should be used to differentiate abuse from non-abuse.”

Children under age 3 have the highest mortality rates due to abuse and neglect, and babies are particularly vulnerable, Brownell said, especially in the months after leaving the hospital.

“At the age of 2 months, babies cry a lot and the biggest trigger for abuse is inconsolable crying or colic,” Brownell said. “That’s when we see an increase in head trauma.”

Though the Department of Health and Human Services has partnered with Maine’s hospitals to educate parents about the danger of shaking a crying baby, that advice, Brownell said, is quickly forgotten if a parent uses substances or is sleep-deprived and unable to calm a colicky infant.

The risk increases for babies if they are born drug dependent. They can be difficult to soothe while weaning off opiates ingested in the womb.

Lack of understanding

With 901 Maine babies born drug dependent in 2020, many parents faced additional challenges in caring for their infants. If they are struggling with their own substance use and lack of parenting skills, the risk factors for their babies spikes even higher.

“We do see a generational phenomenon with difficulty of parenting,” said Brownell. “A large risk factor for abuse is lack of understanding the development norms for a child. If the parents don’t understand why a baby is crying or how to help that child, it can lead to devastating injuries.”

Deaths or brain damage are not caused by a subtle shaking, Brownell explained.

“This isn’t just patting a baby on the shoulder,” Brownell said. “This is violent shaking back and forth or side to side of the infant’s body, so the head and neck will violently flex and extend.”

The violent shaking can cause bleeding and swelling of the brain. Oxygen hypoxia, which restricts blood flow to the brain, may also occur, causing death.

RELATED: Premature birth, premature death: The sad, tragic life of a Maine child

“If a child is injured and brought into the hospital immediately, there will be a different outcome versus languishing at home and not receiving any medical care,” Brownell said.

Often parents delay seeking treatment for the baby because they fear losing custody of their child or being charged criminally. Sometimes parents don’t realize they’ve harmed their infant.

“I’ve heard of circumstances where the parent will shake the baby until (it stops) crying, believing it worked,” Brownell said. “But it’s because the baby loses consciousness. They may not realize the significance of what happened until the baby starts to have seizures or isn’t able to feed normally.”

Brownell also evaluates infants who have fractured ribs or broken legs and arms.

“Rib fractures happen when there is violent squeezing of a baby’s chest,” Brownell explained. “Hands can wrap around the infant’s chest from front to back, generating enough force to cause those fractures.”

When an infant’s legs or arms are broken, they are often put in casts and given medication for the pain.

“If the baby breaks a femur thigh bone, sometimes they end up needing a cast from their ankles up to their abdomen,” Brownell added.

Missing signs of abuse

Along with diagnosing child abuse, Brownell is vice chair of the Maine Child Death and Serious Injury Review Panel. It meets monthly to review cases involving child neglect and abuse, and looks for patterns contributing to deaths and injuries.

One of the panel’s concerns is that the state’s child protective workers and healthcare professionals are missing signs of abuse when they dismiss minor injuries like cuts or bruises.

“A bruise isn’t a significant medical injury,” Brownell said. “But you have to think, ‘Why did this child get a bruise?’ Infants shouldn’t be bruised when they’re being taken care of. That injury is a way for a baby or a young child to tell us that something is unsafe in my home, and I need help.”

While bruises or abrasions are not life-threatening, when they appear on an infant younger than 6 months they are considered “sentinel injuries,” and must be reported to the state’s child protective agency, said Mark Moran, chair of the state’s child death and injury review panel. If they are ignored, Moran said, the infant is at risk of repeated abuse and death.

“DHHS began mandating that sentinel injuries in babies be reported after a highly publicized case involving Ethan Henderson,” Moran said. “He had an injury that was not properly identified and was subsequently killed.”

Henderson, of Arundel, was 6 weeks old when medical professionals failed to report his broken arm to the state’s abuse hotline. The baby also had bruises that were ignored. After an anonymous caller reported that the infant was being abused, a child protective worker visited the family’s home. The caseworker concluded Ethan was safe despite never seeing the infant, who was sleeping at the time.

Three days later, Ethan’s father squeezed the boy’s head between his hands and flung him into a chair. Ethan was 10 weeks old when he died of brain injuries in May 2012.

Mandated reporting of any injury to a baby younger than 6 months takes away any subjectivity or flawed decision-making, Moran said.

“Rather than rely on whether the family presents well or if the physician examining the baby feels like the parents are being truthful about the injury, the law requires that they report the case,” said Moran.

Along with chairing the state’s child death and serious injury review panel, Moran works as the family services coordinator at Bangor’s Eastern Maine Medical Center. When the hospital receives referrals about suspected abuse or neglect cases, Moran consults with Brownell to ensure that the children are properly evaluated and treated.

Reporting is crucial

In a spring 2020 newsletter to the Maine Board of Licensure in Medicine, Moran reminded medical professionals that it is crucial to report bruises or marks to the state’s child protective hotline whenever babies are involved.

Moran cited cases in which healthcare providers overlooked or misdiagnosed injuries, resulting in devastating consequences. An infant with unexplained ear bruising later suffered head trauma.

Another baby with broken blood vessels in its eye was wrongly diagnosed as having constipation. The infant later died due to head trauma.

Bruising in children under age 4 involving the ears, eyelids, neck or torso should also prompt further evaluation, Moran said.

“The hope,” he added, “is that if we can identify abuse properly early on, then we can protect the child from that high level of risk and end up seeing them in the intensive care unit in a coma or worse.”

In one recent child homicide, bruises were apparent months before 3-year-old Maddox Williams was beaten to death in Stockton Springs.

In March, Andrew Williams noticed his son Maddox had bruises on his back and a cut over his eye. When Williams asked his ex-wife Jessica Trefethen about the marks, she said her 4-year-old son had thrown a toy at his younger sibling.

Three months later, Trefethen was charged with depraved indifference murder. Maddox died of blows so severe they fractured his spine, and caused bleeding in his abdomen and brain.

While medical professionals, teachers and childcare centers are considered mandated reporters, Moran and Brownell believe everyone has a responsibility to call the state’s abuse hotline if they suspect a child is being abused or neglected.

“It’s everyone’s responsibility to make sure our children are safe,” Brownell said. “If someone sees something or is concerned, they need to speak out and protect these kids.”

The sooner an injury is reported, the better chance the child and family have to seek services through Spurwink or other agencies that can help prevent serious harm or a tragic death.

“I’m not the type of pediatrician who gets Christmas cards from parents,” Brownell said, “but I do see families that learn to get the support and help they need to successfully parent their child.”

Maine’s child abuse hotline is available 24 hours a day, seven days a week. If you suspect child abuse or neglect, call 800-452-1999. Calls may be made anonymously. Click here for more information on the reporting process.