Sea level rise, intensifying coastal storms and rising construction costs converged to drive up annual Maine home insurance rates by an average of 15 percent this year, a recent report found.

That number is expected to balloon to 19 percent by the end of the year, the second highest increase in the country, behind Louisiana. Under this scenario, Maine would see average annual rates go from $1,322 to $1,571, according to Insurify, the online insurance comparison company behind the report.

And although Maine’s average rate is still one of the lowest in the country (the national average was $2,377 in 2023, according to Insurify), such a rapid rise demonstrates the vulnerability of Maine’s historically low rates to both the natural disasters occurring locally and the global and national trends hiking up insurance rates.

As insurance companies pay out more and more claims in the wake of severe storms, they are also burdened with rising rates for insurance to back their own assets through reinsurance, costs that are ultimately passed on to customers through higher rates.

Both those reinsurance rates and severe storms are expected to rise with climate change.

The chairman of one of the world’s largest reinsurance companies recently said that high insurance costs still aren’t enough to dissuade risky investments in climate change-imperiled areas, even as Insurify’s analysis shows that insurance premiums nationwide increased by nearly 20 percent between 2021 and 2023.

This year, the U.S. has already seen 11 natural disasters that each caused more than $1 billion in damage. Federal weather officials projected an above-average hurricane season for 2024, and the earliest Category 5 hurricane on record tore through the Caribbean this week.

Back in Maine, Greg Thayer, a manager for Sanford-based Batchelder Bros. Insurance, said these rising insurance costs will not be spread equally among Mainers.

“When you look at Maine and see (average insurance premiums) going up 19 percent, that is slightly misleading,” he told The Maine Monitor. “You’re not seeing that across the board. It really is focused on places with particularly high wind events… and a lot of that is driven by the coast.”

Some national insurance companies are already pulling out of coastal areas, The Quoddy Tides reported in March, citing damaging winds and flooding.

The rate increases coming from insurance companies that have stuck around Maine also don’t necessarily account for the catastrophic damage incurred from the January and March storms that rocked Maine’s coast, Thayer said, nor the extreme flooding central and western Maine saw in December.

Because companies rely on lagging data, their premium costs only recently started to catch up with the realities of reinsurance prices and severe storm damage.

Their metrics for calculating those risks will only improve with the use of technology like lidar, a laser sensing method that can map tree coverage in high detail, revealing which houses are at risk of tree damage and fine-tuning premium costs for the most vulnerable zip codes.

“I do suspect that will start to turn in the next 18 months,” Thayer said. “That lagging data will be caught up by 2026… You’ll see deductibles going up just with inflation anyway, and on top of it you’ll have people in high wind areas.”

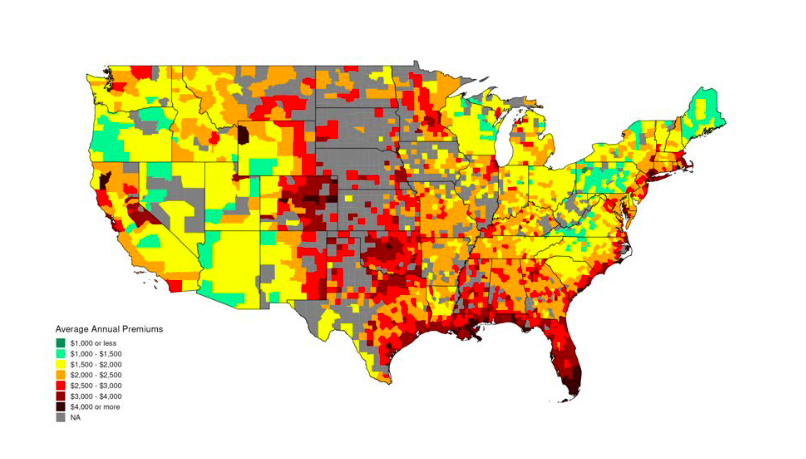

The geographic variance described by Thayer is glaringly apparent in a working paper published last month by the National Bureau of Economic Research, which used a novel technique of analyzing mortgage escrow payment data to map average home insurance premium costs by county. (The practice of mapping insurance rates by zip code is difficult, according to Bloomberg Green, because insurance companies have fought against it.)

On the Maine map, yellow blotches appear over the state’s mountainous spine, encompassing Piscatquis and Franklin counties, along Maine’s Midcoast, from Lincoln County up to Hancock County, and in York County.

The yellow represents higher premiums of $1,500 to $2,000, while the light green that covers the rest of the state shows premiums of $1,000 and $1,500.

“The map shows a clear gradient in insurance costs, with higher insurance burdens in the riskiest coastal areas along the Gulf of Mexico and the East Coast,” researchers Benjamin J. Keys and Philip Mulder wrote.

But rising premiums should not dissuade Maine homeowners from shopping around for more competitive policies, Thayer said.

“Everybody can expect that their policies are going to go up,” Thayer said. “If they’re seeing a policy go up 20 percent it’s probably a good idea to” reconsider their plan. Changes around 8 percent to 10 percent, however, are an expected baseline.

In a June update from the Maine Climate Council, state experts reiterated the need for thorough analysis of all of Maine’s insurance sectors, not just home insurance, to help guide local development decisions and account for risks related to climate change.

Those considerations are what some reinsurance companies are looking for: managed retreat from areas prone to disasters and climate resilient infrastructure.

“Risk reduction through adaptation fosters insurability,” said an economist for a global reinsurance company.