For 27 years, Tony Pushard was in and out of a county jail or the state prison.

His lengthy rap sheet includes convictions for disorderly conduct, assault, drug trafficking, burglary, theft, failing to appear in court and violating conditions of release.

The Augusta man, now 47, remembers the day he finally had enough.

It was Sept. 13, 2013, and he had just been arrested again after three days of heavy drug use. He was facing two years in the state prison and didn’t want to go back. His attorney got him into the Co-Occurring Disorders Court, a specially designed program to help people with substance use disorder and mental illness get clean with a chance to turn their lives around.

“What I needed was support, I needed structure, I needed heavy accountability,” Pushard said during a conversation last fall at an Augusta coffee shop.

Six years after Pushard completed the program, similar court programs across Maine had 295 active participants in 2019, the largest number in any year since the programs began in 2001, according to the most recent Annual Report on Maine’s Drug Treatment Courts, which was released in mid-February. The programs have a track record of success, but are not available to all defendants.

RELATED Due Process: Inside Maine’s county courthouses

“There are not sufficient resources to begin many of the specialty courts that have been shown to reduce (repeat offenses), and improve the lives of children and families,” said Penobscot and Piscataquis county District Attorney Marianne Lynch.

The need to expand the availability of these types of court programs is one of the five key findings of a Maine Monitor investigation of the county court system that began last July. Maine Monitor reporters, editors and photographers conducted dozens of interviews, spent many hours in courtrooms, legislative hearing rooms, commissions and task force meetings, and drove hundreds of miles across Maine to examine the system’s fairness and whether it offers equal access to justice from one part of the state to another.

1. Courts need more reliable and accessible data

From the former chief justice of the Maine Supreme Judicial Court to activists working to change state law and courtroom practices, there’s agreement that the single biggest roadblock to change is a lack of reliable data. Task forces and commissions that met throughout 2019 struggled to gather the data needed to make solid recommendations.

“All of those groups are working from some data, a lot of good-faith estimates and anecdotes,” former Chief Justice Leigh Saufley said in December. “That is what we are hoping in the future to dramatically improve upon with real, hard data.”

Right now the court system is unable to provide statistics even seemingly as basic as the number of convictions, plea agreements or cases that went to trial in a given year. Tracking trends by region, comparing pretrial incarceration rates or trying to compare OUI sentences in York and Penobscot counties, for example, is nearly impossible with the current data, The Maine Monitor found.

The Maine Pretrial Justice Reform Task Force noted in its December 2019 report that a lack of data hampered efforts to agree on recommendations.

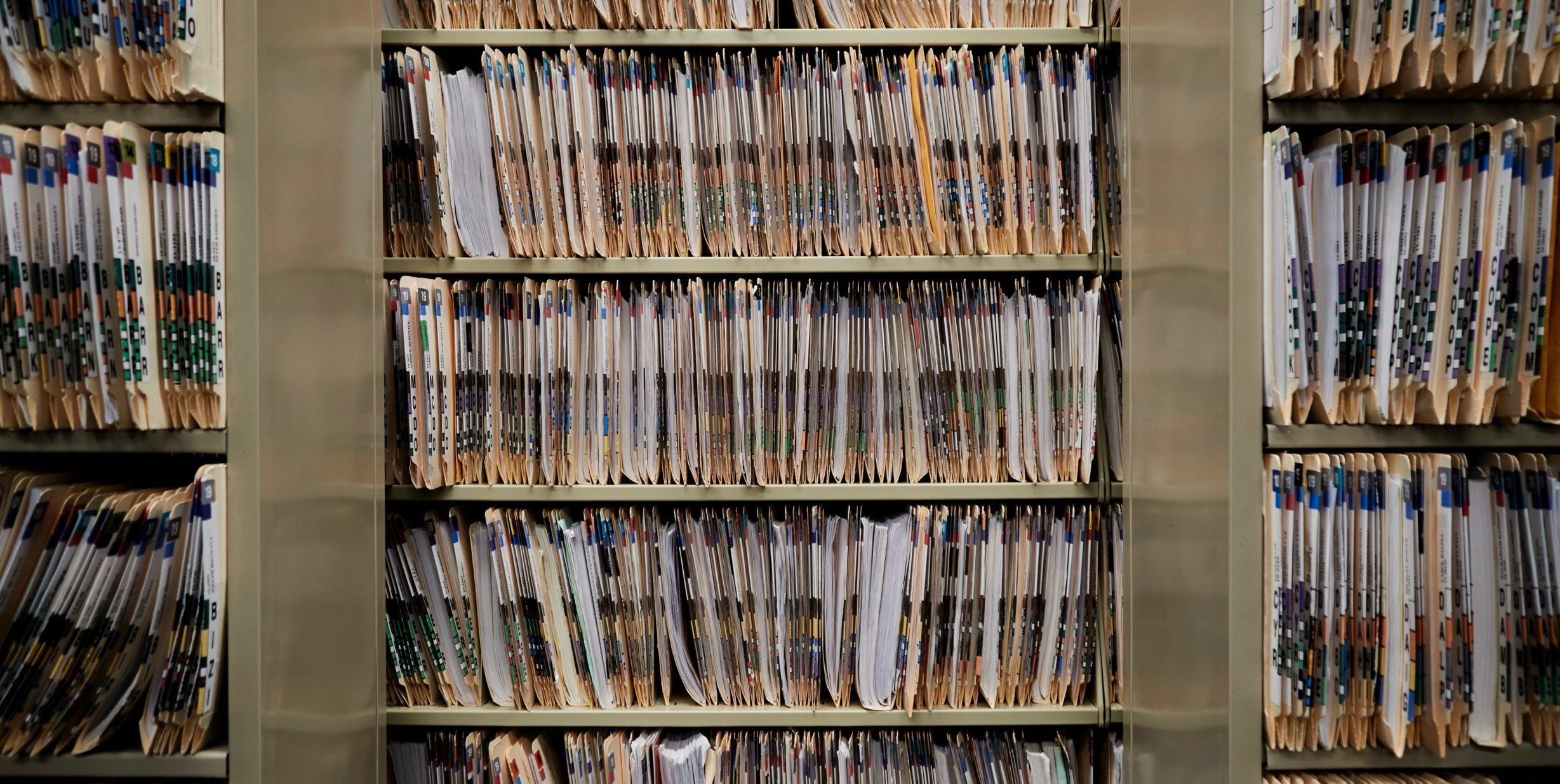

Since 1997, the courts have operated on a system that relies on thousands of paper records. But that will begin to change later this year or early in 2021 when the state switches to an electronic system to manage case filings.

The state hired Tyler Technologies in 2016 to implement a system called Odyssey, used in 30 other states. The judicial branch wants to install re:Search, which will provide a search engine to pull data such as all filings on a specific date, person or type of crime.

“Learning more about what’s actually in the court in the various regions will help us get resources to them, the right amount of resources for what they need,” said Saufley, who is now dean of the University of Maine School of Law.

The need for data must be balanced by a concern for privacy, Ed Folsom, a Biddeford defense attorney, told The Maine Monitor in February.

“I would like to see (clients) be able to get out from under some of these clouds that hang over their lives,” he said. “The more that is out there for people to see, the more difficult it is for you to ever overcome this stuff.”

2. Maine’s indigent defense system is not working

Throughout the series, The Maine Monitor reporters often heard a common refrain: The state needs to reform the way it provides legal representation to low-income defendants.

“Most people would be shocked if they saw the way many indigent defendants are treated,” said Doug Dunbar, a recovering alcoholic and convicted felon who champions major reforms for the state court and county jail system.

Dunbar totaled 136 days in two county jails in 2017 and 2018 as part of the sentence following his sixth arrest and third conviction for operating under the influence. His time in jail, at the Penobscot County Jail in Bangor and the Two Bridges Regional Jail in Wiscasset, led him to become an advocate for bail reform after he saw the poor and mentally ill unable to post bail.

Dunbar recounted people losing their apartments, jobs, Medicaid benefits and custody of their children because they couldn’t afford bail — before even being convicted.

“This is if you’re innocent or guilty,” he said. “Your life unravels because you can’t come up with 500 bucks in bail.”

In addition, those eligible for free legal counsel through the state’s Indigent Legal Services system are not getting the type of help they need, Dunbar said.

“Unable to leave jail, the poor are further harmed through the substandard representation they receive,” Dunbar said. “I don’t know if a Public Defender system is the answer, but something must be done.”

Lawmakers also want to make changes to the system, following a report last year by the Sixth Amendment Center, which found that Maine’s system of providing legal representation to the poor fails to consistently provide high quality legal help. Lawmakers adjourned in mid-March following concerns about the spread of the coronavirus in Maine and may — or may not — return this year to finish work on pending legislation.

“When we return, we’re definitely going to need to look at reforms of the Maine Commission on Indigent Legal Services,” Sen. Shenna Bellows (D-Manchester) a member of the Legislature’s Judiciary Committee, told The Maine Monitor in March.

3. Maine should invest in court personnel and social services that can help prevent criminal behavior

When The Maine Monitor surveyed Maine’s district attorneys late last year, nearly all of them indicated a lack of money is hampering their efforts.

“The criminal justice system is in desperate need of more resources,” said Andrew Robinson, president of the Maine Prosecutors Association, and DA for Androscoggin, Franklin and Oxford counties. “Across the state of Maine, each prosecutor carries a caseload that far exceeds the maximum amount any prosecutor should be required to oversee by any objective standard.”

He went on to describe “a triage type of analysis to determine where we should focus our resources, which is incredibly stressful when you know you are charged with ensuring justice for all cases.”

In Penobscot and Piscataquis counties, Lynch noted a need for “additional clerks, judges and judicial marshals.”

In Cumberland County, one staffer makes a large difference in defendants’ outcomes. Diversion Clerk Katherine Ellis provides direct guidance on how to live up to the terms of deferred dispositions, agreements that give people who plead guilty to certain crimes a chance to clear their record. This is among the positions district attorneys in other counties say they don’t have because of a lack of funding.

In April, Cumberland County District Attorney Jonathan Sahrbeck said he would like to see community programs to address childhood trauma that often leads to substance use disorder and criminal behavior.

“To me, prevention is one of the key things we all need to work on to keep people from coming into the criminal justice system,” Sahrbeck said. “Had we addressed the trauma, they probably wouldn’t have gone down that road.”

It would be a long-term investment. But as head of the state’s busiest prosecutorial district, Sahrbeck said he sees the roots of the childhood trauma coming from parents who were incarcerated or children who experienced homelessness, food insecurity, physical abuse, poverty and drug abuse.

Providing police with options other than jail or the emergency room and beefing up community mental health services would help now, but early intervention with children is the key, he said.

4. Major reform will likely be delayed for several months due to the coronavirus

Dozens of bills that propose to make changes to Maine’s criminal justice system are on hold with an uncertain future because the pandemic forced legislative leaders to abruptly adjourn the session in March with no set return date.

Some of the criminal justice bills propose to address how juveniles are punished and rehabilitated, whether steps can be taken to reduce the use of cash bail and whether some crimes should be reduced to civil offenses.

There are 53 bills related to criminal justice or judicial issues in limbo. In recent weeks, Republican legislators have rejected two calls by Democratic leadership to come back to session. Gov. Janet Mills could call lawmakers back to Augusta but the scope and scale of the work that would be done is likely to be limited.

5. Treatment courts are effective but not universally accessible

Another finding of The Maine Monitor’s investigation is that specialty treatment programs offered in some parts of the state have proven effective – but not everyone has access to them.

A report released in February examining the effectiveness of the state’s Adult Drug Treatment Court recommended that another location be added.

“There is interest in expanding the treatment courts in Maine, with the greatest need and support for an (adult drug treatment court) in the Midcoast region,” according to the report.

Last year, Adult Drug Treatment Courts operated in six counties: Androscoggin, Cumberland, Hancock, Penobscot, Washington and York. In Kennebec County, the Co-Occurring Disorders Court (for those with substance use disorder and a mental illness) and a Veterans Treatment Court also provided services.

Statistics show these programs significantly reduce the likelihood someone will reoffend. These statistics are highlighted in the report:

• Recidivism for drug court graduates is 16 percent;

• Recidivism for those who applied but were not accepted into the program was 32 percent;

• Recidivism for those with a similar risk incarcerated at the state prison was between 28 and 47 percent

In addition, for every $1 spent on drug courts in Maine, an estimated $1.87 is saved by the state’s criminal justice system, according to the report.

Before completing the Co-Occurring Disorders Court, Pushard said he was in a cycle of arrest, conviction, incarceration, release and rearrest.

“I’d go to jail about every six months,” Pushard said, adding that over time, he spent about 12 years in jail or prison. “You make all these big plans that when you get out you’re going to stay sober. Then you get out and you’ve got nothing. You go back to what you know.”

To get into the program, Pushard had to serve an initial six months in jail, with the rest of his sentence suspended while he was out in the community participating in the program. He had to go to counseling, was subject to random drug tests and had to appear before a judge regularly.

He said it gave him the type of accountability he needed to change “the trajectory of my life.” It gave him the foundation to go back to school and the drive to do something meaningful. He’s now a state licensed counselor who works to help others turn their lives around.

“I know the desperation, the pain and the suffering that comes with addiction,” he said. “Also, the desire to stop and wanting to stop and not being able to. I understand it. I’ve lived with it for so many years. That gives my life meaning. That gives all of my experience meaning.”

Maine Monitor reporter Julie Pike contributed to this story.