Maine has earned an “F” from a national organization’s first-in-the-nation assessment of accountability and transparency across the 50 states.

Maine ranked 46th in the “State Integrity Investigation” by three nonpartisan, national and international journalism and good government groups.

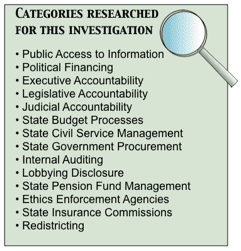

The score was based on research into 330 indicators on both the laws and practices in 14 categories, from procurement to campaign disclosure to lobbying.

No state got an A, leading the groups to conclude “statehouses remain ripe for self dealing and corruption.”

A leader of the study said a low score means Maine lacks the laws, regulation and enforcement to ensure residents are “getting the performance they hoped to see” from state government.

“For a state that ranks towards the bottom like Maine, these numbers matter a lot because they may help explain why budgets are not flush, why roads aren’t repaired, why there are tax loopholes,” said Nathaniel Heller, executive director of Global Integrity, which collaborated with the Center for Public Integrity and Public Radio International on the investigation.

In Maine, the research was done by the Maine Center for Public Interest Reporting, based in Augusta. The Center’s research was then analyzed by the three sponsoring groups, which came up with the scores.

Major funding for the State Integrity Investigation is provided by Omidyar Network and the Rita Allen Foundation. Additional support is provided by the Rockefeller Family Fund.

No states received an “A” from the investigation and only five got a grade of “B.” Maine was one of eight states to get a failing grade. The others are North Dakota, Michigan, South Carolina, Virginia, Wyoming, South Dakota and Georgia.

While those states are not generally known for high-profile corruption cases, some states that are notorious received some of the best grades. New Jersey, for example, got the highest score, a B+.

A statement from the survey groups CPI explained the apparent contradiction:

The study “does not rely on a simple tally of scandals. Rather, it measures the strength of laws and practices that encourage openness and deter corruption. … States with well-known scandals often have the tough laws and enforcement that bring them to light.  ‘Quiet’ states may be at a higher risk, with few means to surface corrupt practices.”

‘Quiet’ states may be at a higher risk, with few means to surface corrupt practices.”

Maine got an F in nine of the 14 categories, including executive accountability. A problem that contributed to that score was that fact that no agency oversees the ethics of top-level state officials, from the governor to department heads, from the attorney general to the state auditor.

It also got F’s in public access to information, civil service management, pension fund management, the insurance commission, legislative accountability, lobbying disclosure, ethics enforcement and redistricting.

The state got a D+ in judicial accountability and political financing and a C- in the budget process and procurement. It got one A: in internal auditing.

Other highlights in the report include:

• While the state collects financial disclosure statements from executive branch employees, the ethics commission has never mounted investigations of those disclosures, according to Jonathan Wayne, executive director of the Commission on Governmental Ethics and Election Practices.

A 2009 report by the commission states: “Maine is one of 11 states which do not have an independent agency that regulates the professional ethics of the executive branch of government.”

Wayne said, “We barely have any jurisdiction. We’re limited to legislative ethics.”

That means problems, including possible conflicts of interest, can fall through the cracks.

• Maine has no “revolving door” law covering top state officials moving into the private industries they had regulated.

A case study occurred in 2007-2008 when Maine’s chief utilities regulator, Kurt Adams, negotiated for and ultimately accepted a job offer and “equity units” or shares from a prominent wind power developer while still head of his agency – and when the developer had business before the agency.

Adams left his job as the head of the state’s Public Utilities Commission in May, 2008 to work for First Wind. Later, Adams and company officials said that despite statements First Wind had made in federal filings about when it had granted him the shares, the company had made a mistake and had granted the securities only after Adams had left the PUC in mid-May.

A subsequent investigation by the state’s attorney general found that Adams had violated no state laws – an illustration of the fact that Maine has no meaningful revolving door regulations, said Maine League of Women Voters former chairman Ann Luther.

“I think there’s a hole there, no restriction at all,” Luther said. “There’s nothing there, nothing!”

• The financial disclosure requirements for constitutional officers, legislators and executive branch employees don’t provide much meaningful information.

They list only income, not their full range of assets.

That means the value of their homes and investment properties, for example, are not disclosed, nor is their stake in any business.

Also, the income disclosure requirement does not ask for precise amounts or even ranges – just a source of any income if $1,000 or more.

That means the public has no way to determine if an official became wealthy while in office or the extent of conflicts between their private interests and public responsibilities.

Take the 2009 disclosure form for Democratic state Sen. Justin Alfond, a member of one of Maine’s wealthiest families.

Alfond’s disclosure is more comprehensive than most. But even in his case, readers will only learn that each source identified represents income of “$1,000 or more.”

The liability side of the standard disclosure form is equally vague, requiring only the listing of “names of creditors for any unsecured loans of $3,000 or more that you received during the reporting period.”

Then-Rep. Kenneth Fletcher’s 2009 disclosure reports such a loan from PretiFlaherty, one of the state’s leading law firms. Anthony Buxton, a senior member of the firm, is a leading energy industry lobbyist in Maine, appearing frequently before the Utilities and Energy Committee on which Fletcher, a Republican, sat as ranking minority member.

Fletcher’s form indicates the loan was in connection with Buxton’s assistance to a non-profit group headed by Fletcher whose goal was to prevent the removal of a dam that created a lake on which Fletcher lived.

Fletcher is now director of Gov. Paul LePage’s Office of Energy Independence and Security.

Also, the disclosure forms require virtually no details on investments.

The form filed by Secretary of State Charles Summers in 2010 is illustrative: In the section marked “Other sources of income,” Summers lists “investments” with the “UBS Financial Services.” But there are no details as to which mutual funds, stocks bonds or companies are included in those investments.

• The state’s one top grade was for the Department of Audit, which scored high because it is protected by law from political interference, has a professional fulltime staff, is well-funded, can initiate investigations and its reports are widely available.

• Budget deliberations, the legislature’s most important activity, are tough to monitor, according to veteran observers.

“Only members of the Appropriations Committee are able to spend the time to understand the budget,” said former Sportsman’s Alliance of Maine lobbyist George Smith. “The budget is an insider’s game.”

Even then, the complex set of documents is “almost impossible for insiders to figure out,” said Mary Lou Dyer, former state labor commissioner and now a lobbyist.

In addition, many budget decisions recently have been made in closed political-party caucuses, according to veteran social-services lobbyist Elizabeth Sweet: “The process has gotten ever more secretive.”

• While Maine has a strong law ensuring access to public information, sources also said there were significant problems with that law in practice. The process to appeal a denial of an information request, for example, is expensive and complex.

Judy Meyer is vice president of the Maine Freedom of Information Coalition and managing editor of Lewiston’s Sun Journal.

She gave a “capital ZERO” score to the survey question that asked whether “In practice,” she said, “citizens can resolve appeals to information requests at a reasonable cost.”

Said Meyer: “There was one guy who spent over a million dollars (to mount an appeal). You have to hire a lawyer, file a lawsuit and there are very few lawyers in Maine who do this … they’re very expensive. A lot of people don’t appeal because of this. They throw their arms up and say ‘What can I do?'”

Jeff Inglis, president of the Maine Pro Chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists and managing editor at the Portland Phoenix, said that resolution of an appeal “requires, at minimum, legal threats” and “can take an unspecified amount of time and money.”

Inglis said an aide to former Gov. John Baldacci told him and his publication, “So sue us,” when the Phoenix filed an information request for politically sensitive documents.

• One year into the four-year term of Republican Gov. Paul LePage, it appears he is less answerable to the public via the statehouse press corps than recent predecessors.

“He has no regularly scheduled news conference or availability,” said veteran statehouse reporter Mal Leary. “All the governors I have covered held news conferences either on a schedule or held them on an issue basis about once a week.”

Peter Rogers, LePage’s communications director until February 2012, defended LePage: “Since I have been in the administration the governor has done major press conferences with time allocated for media questions. He has also responded to a number of media requests for interviews.”

• One item in the state budget is – by law – off limits to scrutiny.

Although Maine’s governor earns only $70,000 a year — the lowest governor’s salary in the country — he also gets $30,000 annually in quarterly payments that he can use at will.

According to Sandra Harper, associate commissioner of the Department of Administrative and Financial Services, “there is no detailed documentation of the expenses.” In fact, the law establishing the account states: “This account shall not be subject to audit, except as to total amount to be paid.”

• Legislators are prohibited by law from accepting more than $300 in goods or services from a single source within a calendar year. This seems a high number to some good-government watchdogs.

“Compared to other states, I would expect $300 to be a relatively high threshold,” said Wayne, the ethics commission director.

Doug Clopp, deputy program director of Common Cause, said, “Ideally, lobbyists should be barred from giving gifts of any amount, at any time. I understand the reality of asking a legislator to lunch to have a discussion about policy, but the limit should be $25.”

Heller, from Global Integrity, said the “second phase” of the project begins immediately. He said the groups want to work with state officials across the country, good government groups and others to “put together a roadmap for reform.”

Because they expect there to be both financial and political obstacles, “we don’t expect this to be done in one fell swoop… We’re playing the long game here.”

Barbara Walsh, Mary Helen Miller and Jeff Clark contributed to this report.