A new analysis by the nonprofit Union of Concerned Scientists finds that at least 20 to 30 pieces of “critical infrastructure” in Maine will face frequent, disruptive tidal flooding in the coming years and decades.

Even in an optimistic climate change scenario, three Maine Superfund sites and two brownfields are at risk of flooding every other week by 2030, which could spread dangerous contaminants.

If sea levels rise just over 3 feet by 2100 — what climate scientists consider a moderate scenario — tidal flooding could occur biweekly at four wastewater treatment plants in York County, once a month at nine sites in Portland and eight in Bath, and at least twice a year at five Maine post offices, from Ocean Park to East Machias.

With sea level rise accelerating in Maine, according to the state Geological Survey, the new study describes looming deadlines for action in coastal communities that depend on the buildings most at risk.

Penelope Overton’s report on this for The Portland Press Herald, with a great map, is well worth reading; you should also check out The Monitor’s Unstoppable Ocean project, which looked at how ten communities in Maine are preparing for sea level rise, often in radically different ways.

For more, I spoke to study co-author Erika Spanger, the Concerned Scientists’ Massachusetts-based director of strategic climate analytics. Our conversation is lightly edited for length and clarity.

ROPEIK: What makes the sites that you looked at “critical” infrastructure?

SPANGER: Assets and facilities that provide functions necessary to sustain daily life, basically. So that includes schools, hospitals, public housing, energy infrastructure, wastewater treatment plants… types of infrastructure that are essential to daily functioning at the community level, to people’s health and safety.

Community consultation is a large part of what drove us to do this new analysis. We have done chronic inundation analysis in the past, looking at a pretty high threshold of flood frequency, so on average every other week, and we’ve heard from communities that that’s far more flooding than they would be able to tolerate.

So we went back and did this analysis looking at critical infrastructure, and looking at lower thresholds of flooding, so twice a year, 12 times a year.

ROPEIK: What makes these sites vulnerable? What does that actually look like in practice?

SPANGER: In the near term, it’s just going to be garden-variety high tides, with this added sea level, that are going to be inundating really important places on a chronic basis… And this is on the way to permanent inundation.

First, we have these really rare and really noteworthy king tide flooding events, then we transition to chronic tidal flooding, and then eventually we’ve ceded areas to the sea.

So whether a storm ever strikes your community again, tidal flooding is an inevitability for so many. We have, in most cases, really heavily developed coastlines in the U.S…. because we understood the contours of the ocean, we understood where high tide ended.

We’ve added sea-level rise to that, and that enables simple high tides to reach into places where they never did before… and it just needs to “grow a little taller,” as things rise further, to be flooding more. So it’s that really massive deadline that communities face that we wanted to communicate with this work.

ROPEIK: What’s the message to communities here about what needs to happen between now and when these effects become more untenable than they already are?

SPANGER: We found a lot of vulnerability of critical infrastructure in the 2030 timeframe, certainly in the 2050 timeframe. And what that means for communities is they need to be preparing, in the immediate.

We need to be safeguarding what we can and devising plans to relocate critical infrastructure if needed. We need to absolutely stop putting things in harm’s way. No community, no one responsible for managing the kinds of facilities and assets we’re talking about, should be taken by surprise by chronic flooding.

And we need to appreciate that we are driving this sea level rise problem, and we need to be reining in the heat-trapping emissions to get at the root of the problem, so we’re not creating an absolutely untenable situation for coastal communities later this century.

ROPEIK: The report talks a lot about places that people might associate more with sea level rise, like Florida and New Jersey. What should Mainers be picturing when they think about this issue?

SPANGER: Maine is very much a coastal state, and it really has a surprising amount of vulnerability. I was surprised to see some locations that are — City Hall, a post office.

Sites that are vulnerable to chronic flooding in Maine are actually … a representative kind of cross-section of critical infrastructure vulnerability we see around the country. You’ve got some power plant exposure, you’ve got some affordable housing, you have brownfields, wastewater treatment plants.

The scale of this problem coast-wide is hundreds of coastal communities, home to millions of people. It’s important for us to think about what’s involved in, for example, closing just one neighborhood school — the complexity of doing that at the community level.

As we scale up across the entire U.S. coastline to many different types of critical infrastructure, this is a really daunting problem that we really need to see coming.

Explore the study’s findings for yourself with an interactive map.

A note about that heat wave

The Concerned Scientists call May to October in the U.S. “danger season” — the time of year when risks from extreme weather are most pronounced. Maine saw that firsthand in last week’s heat wave.

Portland and Augusta set new daily record highs for June 20 at 94 and 97 degrees Fahrenheit, respectively, according to the National Weather Service.

Across the U.S. and its Caribbean territories, the Concerned Scientists say, 77% of extreme heat alerts since May 1 have had a clear link to human-caused climate change.

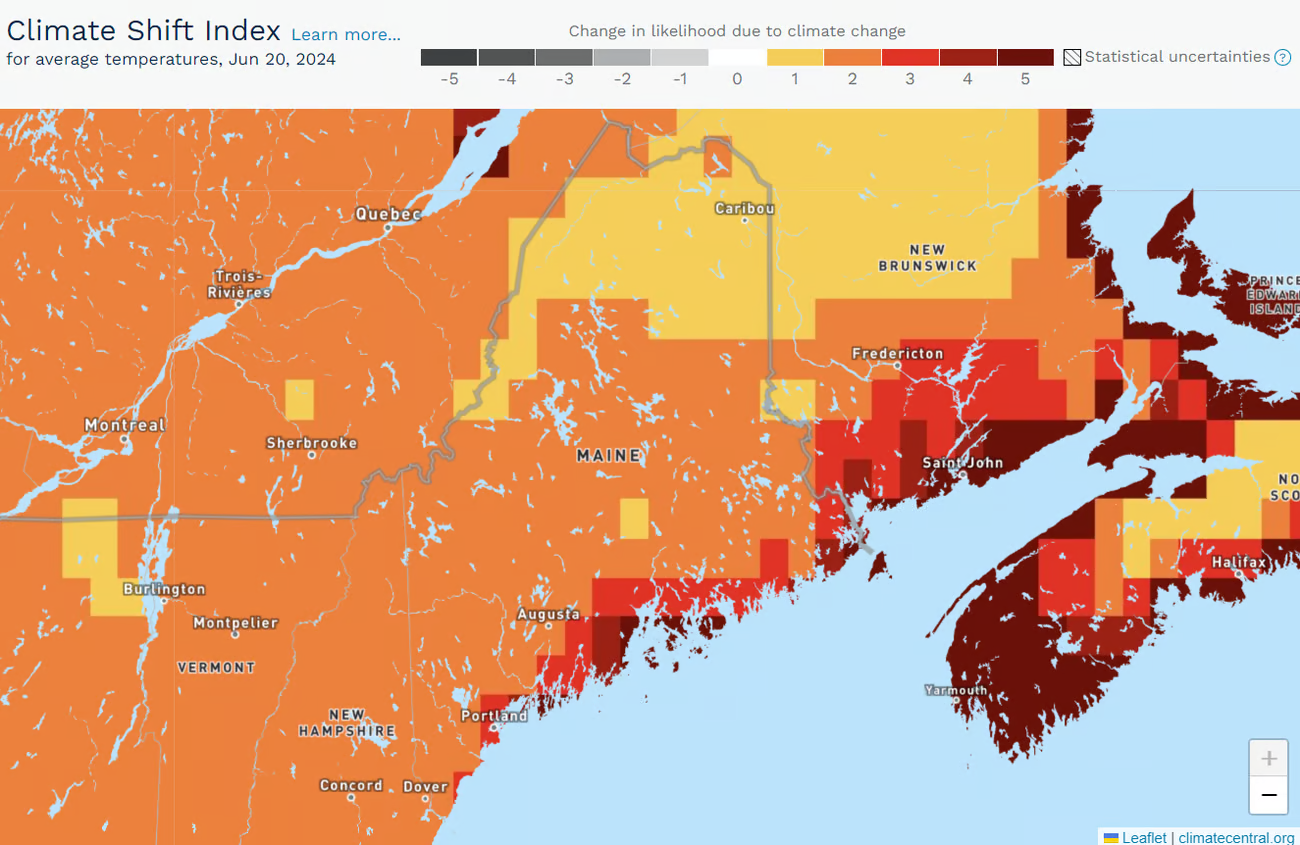

They base this on a tool called the Climate Shift Index, from the nonprofit Climate Central, which uses computer models to see if the day’s weather could have happened in a world without historical greenhouse gas emissions.

This tool shows that the sizzling temperatures on June 20 were made twice as likely in most of Maine because of climate change, and as much as five times more likely along the normally temperate coast.