As the Legislature’s second regular session approaches on Jan. 5, lawmakers have been working behind the scenes to get their proposed bills through the powerful Legislative Council.

Maine’s second session has a defining characteristic: The state Constitution limits the session to “budgetary matters; legislation in the governor’s call; legislation of an emergency nature admitted by the Legislature; legislation referred to committees for study and report by the Legislature in the first regular session; and legislation presented to the Legislature by written petition of the electors.”

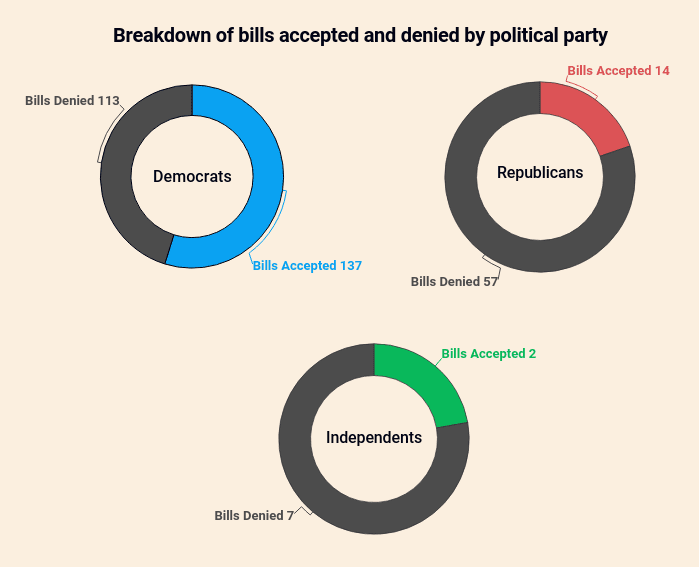

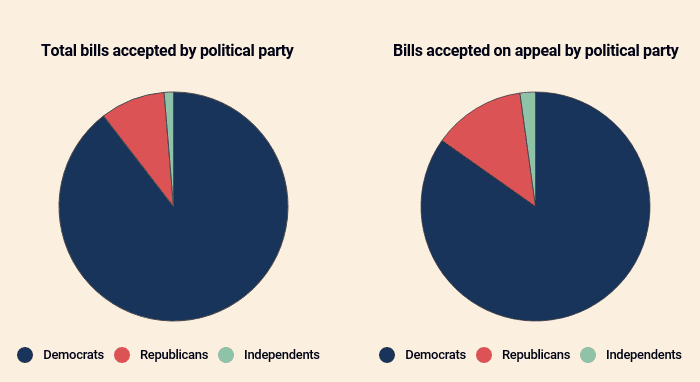

What exactly does “emergency nature” mean? Ultimately the Legislative Council — made up of House and Senate leaders from both parties — gets to decide. This year many of their decisions were settled on party lines, and Democrat-sponsored bills fared far better in making it through the council. On appeal, 39 bills sponsored by Democrats made it through the council, compared to six by Republicans and one by an independent.

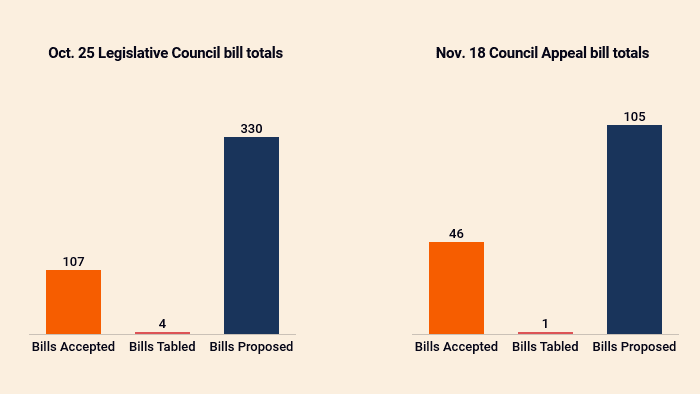

In total, 153 bills made it through the Legislative Council from 330 proposed. Republicans had 14 of their 71 proposed bills accepted.

When lawmakers made their appeals to the council on Nov. 18, most were shot down. One lawmaker said, “it’s like getting your two minutes with the Supreme Court,” a reference to the amount of time per bill lawmakers were given to make their case.

Rep. Ben Collings (D-Portland) quipped that he was “making the (Boston) Celtics’ shooting percentage look better” after his six appeals were rejected before the council. One bill concerned tribal gaming, one would have raised taxes for millionaires, another would have raised taxes on mining operations.

Sen. Matthew Pouliot (R-Kennebec), who is on the Legislative Council, said: “Let’s just take the vote” instead of using his two minutes, knowing there was no chance one of his bills would make it through the Democrat-controlled committee.

Despite hearing more than 100 bills in the appeal process, lawmakers on the council asked their colleagues fewer than 10 questions.

While Republicans were less likely than their Democratic counterparts to get legislation through the committee, the Legislative Council struck down bills from both sides. House Speaker Ryan Fecteau (D-Biddeford) cast the deciding vote to kill a number of bills written by members of his party.

Fecteau said his decision to accept fewer bills than his colleagues was made out of respect for staff, which already had a grueling first session. He said he’s also keenly aware of the number of bills that were carried over, and with an April 20 adjournment deadline, having enough time so the Legislature can work through everything will be a challenge.

“For me, one of the biggest pieces is knowing how burdensome and challenging it is for our nonpartisan staff,” Fecteau said. “To do the work of drafting the bill, processing the bill, getting it through the committee process, having the hearing, having the work session, drafting amendments, drafting floor amendments, finalizing the bill, engrossing the bill, getting the bill to the finish line. …

“I think in their minds perhaps people think things happen overnight, and you wave a wand and a bill goes from being a proposal to law. There is so much more involved in that process.”

What qualifies as an emergency?

Although the Maine Constitution says bills in the second session should be an emergency, it does not define the word, and each member of the Legislative Council votes with their own idea of what qualifies.

For Senate President Troy Jackson, the definition of an emergency is “something that can help people in the state of Maine as early as possible.”

“If you made a good argument about why it was important that it be done right then, and maybe just something that you can tell that sounds like it’s going to be helpful.” That has to be juggled with being as efficient as possible because of a shortened deadline during second sessions, he said.

Pouliot had his own interpretation but admitted, “it’s all in the eye of the beholder.”

“In my opinion, emergency legislation is one that follows the outline that is enshrined in our Constitution,” he said. “Meaning something that, but for that involvement from the Legislature, is going to cause other ramifications. Either negative impacts on life and safety or negative impacts on the Maine economy.”

Fecteau said what one lawmaker views as an emergency bill can vary widely from another because of how the issue affects a given district.

He pointed to a bill that would change the rules of wine distribution in the state. Rosemont Market and Bakery, which has various locations across the state, couldn’t distribute wine being stored in a warehouse in Scarborough, which created a significant barrier and potential loss of money. A bill to resolve that did pass muster.

“I think that’s a good example of just how you have to really take a look at not just what the bill is on its face,” he said. “But also, what is the bill’s value? Or what does it mean to the community of the representative who’s putting it forward?”

Partisanship rises as elections loom

Pouliot, Fecteau and Jackson all agreed that politics can play more of a role in the short session and can have negative effects.

“There’s partisanship all the time,” Jackson said. “We try and limit that, and work with your colleagues on whatever you can to get stuff done.”

Pouliot, the Republican from Augusta, said good ideas can lose momentum purely because of the party affiliation the idea is tied to.

Some may say, “Yeah, that’s a good idea. But if we allow this legislator to go forward with it, and they’re successful, that’s gonna be like a win in their columns, their campaign,” Pouliot said. “So what? Even if a Democrat has a good idea, and I held the strings on what goes forward and what doesn’t, I would still want their bill to have a public hearing.”

Pouliot said he hasn’t had the chance to prove that point, but would look forward to it if Republicans flip the state Senate.

Fecteau said there is always some level of partisanship, but he has faith that Maine legislators are willing to work together on important issues. He also said that compared to his last time on the Legislative Council, when Republicans controlled the Senate, he believes more bills were approved this time and more bills died when there was a 5-5 split.

Pouliot said a more balanced Legislature better serves Maine’s interests.

“There does not exist balance in Augusta right now,” Pouliot said. “Democrats control both chambers and the Blaine House, and that’s what people voted in. But in doing so, they didn’t vote for balance and compromise in the Maine State Legislature.”

Lawmakers back the process

Whether the role the Legislative Council plays in the second session is good or bad is pretty much irrelevant — it would take an amendment to the state Constitution to change it. Still, some lawmakers think the process is good while others find it useless.

Jackson said compared to other states, he finds Maine’s system to be one of the best because it gives every legislator the opportunity to have bills heard, regardless of party, rank or anything else.

“Most states aren’t like that at all,” Jackson said.

Pouliot would rather get rid of second sessions altogether and meet every two years, like the Texas Legislature, he said.

“The reality is we have a very unique model in Maine where every bill gets a public hearing, which is a blessing, really,” Pouliot said. “In other states where my colleagues do business, I’ve seen that the chairs will just shove the bill in a drawer and it never gets a hearing. So at least Maine has a more robust process.”

Ultimately, Maine has its quirks, like every other state. Here, the Legislative Council and Appropriations Committee have a lot of power.

“What’s going to be up for consideration is determined by this relatively small group, and within that relatively small group, by the party that holds the majority in that small group,” said Mark Brewer, political science professor at the University of Maine.

In other states there’s also an imbalance, Brewer said.

“It’s hard to characterize state legislative processes in the U.S. because there are all these kinds of unique elements, depending on the state you’re looking at,” Brewer said.

COVID-19’s expected impact

With the session approaching quickly as COVID-19 cases soar in Maine, the virus is certain to play a role in the session.

“If you asked (Senate) President Jackson and I, a couple months ago, or four months ago, I think we would have said, ‘We’re going to head into the second session and we’re going to have a greater sense of normalcy.’ Then you see the case count go up, and you see the hospitalizations and you see deaths, and it’s like, ‘OK, we’re still really in this pandemic,’ ” Fecteau said.

There should be no fighting about vaccines and masks because Republican-sponsored bills to limit the state’s power to enforce requirements failed to make it through the council.

Pouliot said one good thing that came from COVID was allowing constituents to join hearings remotely. With a state as expansive as Maine, giving people the opportunity to weigh in without spending the day traveling to Augusta was a positive for lawmakers and their ability to represent the state.