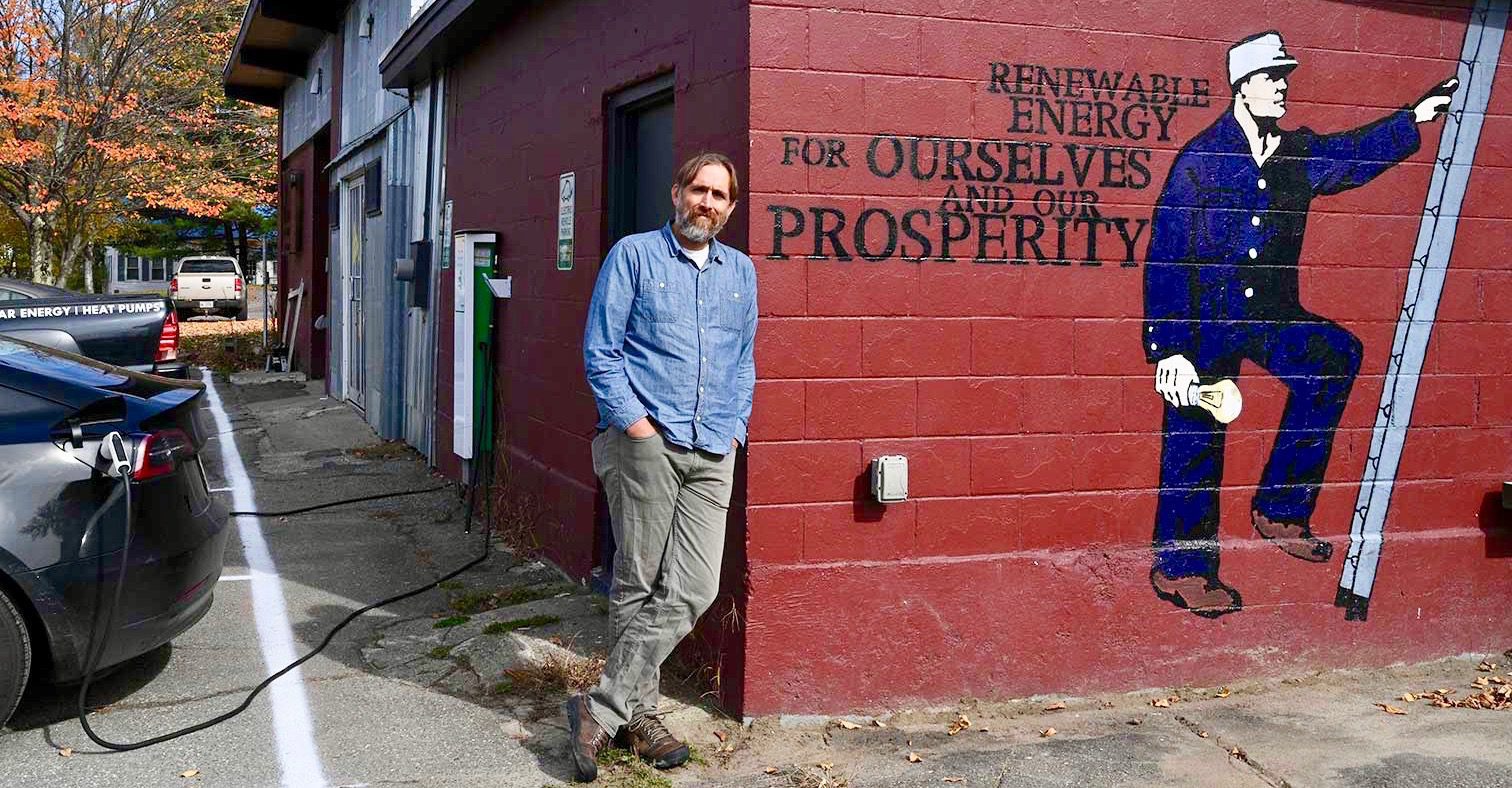

Ascending to his office in Pittsfield, Vaughan Woodruff treads on the same hardwood steps he walked as a third-grader in public school. Now the stately brick building houses several small businesses alongside the solar energy firm he founded more than a decade ago, Insource Renewables.

Woodruff chose the name to highlight “sustainability not just in the environmental sense,” he says, countering the global outsourcing that has created a kind of “collective economic trauma in communities like ours.” Pittsfield had lost manufacturing plants, and Woodruff was determined that his business “would not be another page in the story of loss.”

After earning degrees in civil engineering and education and working in Montana, Woodruff brought his new business back to the area where six generations of his family have lived, and where he wanted his children growing up.

Riding the ‘solarcoaster’

The timing was not auspicious. By 2009, solar rebates began expiring and soon after former Gov. Paul LePage launched a sustained attack on renewable energy. Before long, Woodruff recalls, Maine had “one of the most anti-solar regulatory climates in the country.”

Trying to stave off that “existential threat” to his business, he spent so much time in Augusta that “running the business [seemed] almost secondary at times.” The Public Utilities Commission process is geared toward investor-owned utilities and large industry that can afford representation, Woodruff says, making it frustrating and disproportionately costly for local energy practitioners.

Changing regulations and tax rebates, technological advances and disruptions like President Trump’s tariffs have made for what some in the industry call a “solarcoaster” ride. Solar is a perfect fit, Woodruff quips, for those “who want a job where things won’t be boring.”

SOLARIZING MAINE: Vaughan Woodruff returned to his hometown of Pittsfield in 2009 with his ‘fledgling’ solar energy company. Ten years later, Insource Renewables is a worker-owned cooperative company and one of the state’s leaders in solar energy solutions. This video is produced as a collaboration between Pine Tree Watch, Emmy-award winning documentary filmmaker Charles C. Stuart and The Buck Lab for Climate and Environment at Colby College.

Gaining a new perspective

“Solar kind of encompasses all the different trades,” observes Jeremy Troxell, a project manager at Insource who worked previously as an electrician, plumber and carpenter. Panel installations, he explains, require safety set-up, measurements, setting of fasteners and then “putting it all together like Lincoln Logs. Older houses have a lot of nuances,” he adds, and each site offers different challenges, providing “something new to learn every day.”

Not everyone would relish days spent traversing pitched roofs. But Troxell, a former rock climber, has found that solar work offers a benefit his previous jobs did not – viewing communities around the state from on high: “You see places from a perspective most people don’t get to see.”

Workers at Insource can now participate as member-owners because the company recently became a worker-owned cooperative. It is also a certified B corporation committed to “doing good,” one of only six B corps in Maine.

The chance to have a stake in a growing company was part of what drew electrician Angie Weeks Knapp to Insource after 12 years running her own business. She began as a subcontractor just one day a week and admits that she had no particular interest at first in renewables.

But “seeing the independence” that solar power gives clients and witnessing their enthusiasm, she says, got her “more and more excited” about helping people make that transition.

A lifelong resident of Somerset County, Weeks Knapp knows how scarce dependable jobs there can be and appreciates being in a field where “we’re going to have so much work to do in the next 10 years.” The growth of renewable energy makes her more confident for her children’s future as well: “If they’re interested, something will be there for them.”

‘Here to teach and learn as well as install’

Seven years ago, Royal River Heat Pumps in Freeport was “just me and my truck,” observes its founder Scott Libby. He launched the businesses, after working two decades in the HVAC industry, hoping he could keep himself busy installing highly efficient ductless heat pumps (which draw on electricity to provide both heating and cooling).

To his surprise, steady consumer demand — driven by consistent Efficiency Maine rebates — helped translate into what Libby describes as “very linear” growth for the business, which now has 37 employees. “I’ve never had to lay anyone off due to lack of work,” he notes.

Andrew Fessenden, the company’s first employee and now a lead technician, explains that heat pumps — an increasingly popular option for those generating solar power — often involve coupling different technologies so their installation “takes really being on top of your game.”

Training is “my biggest commitment” as an employer, Libby says, one that “gets more costly as we grow.” The entire staff spends a half-day in training each month, which amounts each time to “$7,500 in payroll,” plus the lost-opportunity cost. But that investment is vital, Libby believes, both for “correct installation and employee retention.”

Well-trained employees, Fessenden says, can share their knowledge with customers, who often don’t understand heat pump technology: “We’re here to teach and learn as well as install.”

‘An opportunity for the state of Maine’

Some in-state programs, like Kennebec Valley Community College’s degree in Energy Services and Technology, provide specific training related to heat pumps. But Libby prefers to hire installers with at least five years’ experience on top of schooling.

In a recent search for new installers, Libby listed on the national site, Indeed, and used the job postings to “sell the company” and the attractions of living in Freeport. The response, he notes, was “humbling.” Applications came in from around the country, he recalls, with “people calling to say ‘I want to come work for you.’”

“I do think there’s an opportunity for the state of Maine,” he says, to draw experienced workers from places battered by “droughts, fires, hurricanes and flooding.” One new employee is moving from California, while another is coming from Kentucky.

“I think Maine is very attractive to people outside,” Libby reflects. Jobseekers on the Indeed site “have to put in a zip code or location and people are putting in Maine.”