The devastating diagnosis would have crippled most people.

But Ken Clark wasn’t most people.

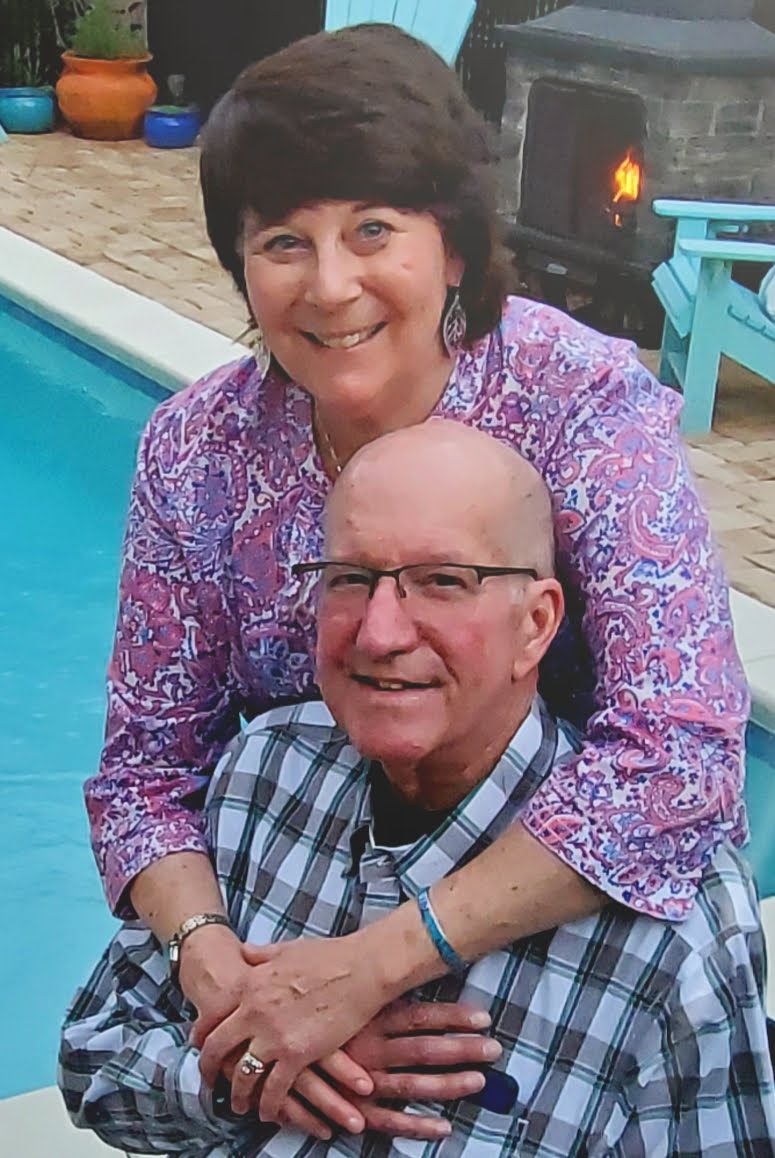

He was a fighter, a Jersey boy, a kid who grew up in a close-knit family. He was a devoted dad, a loving husband, a handy guy who could fix or assemble anything, but would cuss a blue streak while he was at it.

In late 2018, doctors diagnosed Ken with stage 4 pancreatic cancer, an illness with a 3 percent survival rate. Sixty-seven at the time, Ken didn’t dwell on the bleak odds. Surrender was not in his vocabulary.

He had a fun-loving and feisty wife, three grown kids just beginning to make their mark in the world, a good job and a comfortable home in a small Maine town. He didn’t plan on going anywhere. He had a camp that needed fixing, memories to make and milestones to witness.

For 18 months, he fought his cancer like it was a machine that needed fixing. He cussed a lot and endured bi-weekly doses of chemotherapy, including one that nearly killed him. He developed neuropathy, a side effect from the harsh cancer drugs that damaged his nerves and left him unable to tie his shoes, button a shirt or savor a good meal.

Despite the debilitating chemo treatments, 2019 had been a good year. Ken retired from Central Maine Power Co., where he worked as a systems analyst since 1998. He applauded his youngest daughter, Elise, at her high school graduation, celebrated his family and friends at a bountiful Thanksgiving table, and strung an abundance of Christmas lights around his Readfield home.

This year, in early March, Ken felt good enough to travel to northern Florida with his wife, Lori. They spent time with relatives, walked the beach, took a cruise to see dolphins and made treasured memories.

“He was,” said Lori, “so happy the whole trip.”

Not long after they returned to Maine, Ken’s temperature spiked after another chemo dose. On Friday, March 13, after multiple tests the day before, doctors told Ken he had an infected chemo port that caused sepsis, a life-threatening infection. They would also soon learn that Ken had another lethal complication – COVID-19.

As the pandemic began to break in Maine, Lori battled to keep her husband out of the emergency room at MaineGeneral Medical Center in Augusta, afraid of virus contagion.

“I do not want Ken to spend the night in the ER as the pandemic is breaking,” Lori told doctors.

After spending a brief time in an ER overflowing with patients, nurses transferred Ken to a private room. Loaded with antibiotics, he could not eat or sleep. Nurses gave him blood tests every hour. Ken stabilized and felt better for a few days. A former journalist and local librarian, Lori spent most of her time by her husband’s side, comforting him and keeping an eye on his condition and care.

Ken’s children, Sean and Elise, also visited their dad, while his eldest daughter Emily got updates on the phone from her Seattle apartment.

On Tuesday, March 17, Ken struggled to breathe. His oxygen levels plummeted. Nurses placed a mask over his face and connected him to an oxygen tank. They continually increased his O2 as the pulse oximeter clipped around his finger beeped, alerting that Ken’s oxygen was dangerously low.

“He went from being OK the day before,” Lori said, “to getting the highest amount of oxygen they can give you.”

That afternoon doctors ordered a chest CAT scan.

“And then all hell broke loose,” Lori said.

RELATED The Last Responders: Consoling the dying and grieving in the COVID-19 era

The pulmonary doctor explained that the infection had invaded Ken’s lungs, causing severe damage, overwhelming his body’s immune system.

“He’s critically ill,” she said. “He needs to be put on a ventilator.”

With his family’s support and urging, Ken agreed to be sedated, intubated and have a central intravenous line inserted into his neck.

“The next 48 hours,” the doctor explained, “are critical.”

For the past 18 months, he had pulled through this incredible miracle of living through stage 4 pancreatic cancer, life-threatening infections. And then he gets COVID. It was heartbreaking.”

— Lori Clark, Ken’s wife

Before he was intubated, Ken tried to dissuade his eldest daughter Emily from coming to see him. He knew she was busy working on her doctorate in physics at the University of Washington in Seattle.

Ken was worried about interrupting her studies and the inconvenience of a cross-country flight.

But Emily was not swayed. She began searching for a red-eye flight as her mother told her, “things are going south.” Emily was determined to see her father.

Before doctors sedated Ken, Lori, Elise and Sean told Ken, “We love you,” and hugged him goodbye.

The next morning, Wednesday, March 18, Emily flew into Boston and caught a bus to Augusta. Her younger sister Elise picked her up and they raced to the hospital.

When they arrived, the doors were locked. MaineGeneral, like most other hospitals in the state, had ramped up its restrictions due to increased COVID infection. Visitors were barred from entering.

Emily and Elise stood outside the hospital doors, devastated and unable to visit their dad as he lay in ICU, relying on a ventilator to help him breathe.

RELATED The Last Responders: Saying goodbye to Dad

On Friday, March 20, the family received more devastating news.

Ken had tested positive for COVID-19.

His family was shattered.

“For the past 18 months, he had pulled through this incredible miracle of living through stage 4 pancreatic cancer, life-threatening infections,” said Lori. “And then he gets COVID. It was heartbreaking.”

Lori agonized over her husband’s perilous condition.

I don’t want him to die alone, she thought.

Lori began calling the hospital doctors. She cried, and begged for her family to be allowed to visit Ken.

After consulting with the chief medical office, the doctor called Lori and told her, “You can come see Ken.”

“It was a compassionate end-of-life visit,” Lori says.

Early Friday night, Lori ran up the hospital stairs to the ICU room. Her three children waited in the car, hoping they would be allowed in to see their father.

Lori cried when she saw her husband, unconscious and ventilated. Doctors explained that his organs were failing. She held her husband’s hand.

“I love you,” she told him. “I am here for you. The kids want to be with you, too.”

Using her phone, she FaceTimed her children, who were sobbing in the car. Lori held the phone’s camera to their dad, allowing them to say goodbye.

“It broke my heart into a million pieces.”

Before she was told it was time to leave, Lori took a picture of her holding her husband’s hand.

Due to COVID contagion, she was not allowed to stay the night. She came home and emailed and called friends, telling them, “It looks like this is the end.”

The next morning, Saturday, March 21, Lori received a call from the ICU pulmonologist.

“Ken has been more stable the last 8 or 10 hours,” he said. “I’m going to try and pull the ventilator.”

The doctor removed the respiratory tube from Ken’s throat, and miraculously, he could breathe on his own.

Lori and her children clung to a new sense of hope. But the odds against her husband terrified Lori.

“It was like OK, let’s go one day at time.”

Because Lori and her children had been exposed to COVID-19, they had to quarantine. They could not see Ken as he slowly improved. They also could not see friends or family to seek support. Neighbors brought food to the family’s doorstep.

When they were able to speak to Ken, he remained stoic. Rather than talk about his near-death experience, he told his family what he ate for lunch or which nurse was caring for him that day.

Ken had already had many emotional and heartfelt conversations with his family over the past 18 months as he took dose after dose of chemotherapy to keep him alive. He told his wife and children how much he loved them. He told his kids how proud he was of them and their accomplishments. He told his wife how fortunate he was to have married the dark-haired reporter he met at the Wilkes-Barre Times Leader newspaper, where he worked as director of information technology, maintaining, fixing and cussing the large mainframe computers.

As he bided his time in the hospital room, trying to get stronger to come home, he told his family: “I love and miss you.”

He also told them he understood he had the virus.

“Ken was relaxed,” Lori remembered. “We were the ones that were desperately trying to get to him.”

Over the next eight days, as Lori and her children remained in isolation, they clung to hope, and the belief Ken would somehow pull off another miracle.

“It was heartbreaking,” Lori said. We didn’t know where he was with the whole COVID thing, because nobody knew if he would get worse or get better.”

The family FaceTimed Ken, but it was difficult for Ken to hear. He was hooked up to an oxygen tank.

“They had to keep upping the oxygen as he got worse. The sound roars in your ears.”

RELATED The Last Responders: Zooming a final goodbye

Undaunted, Ken texted his family. He sent a selfie. His lips were cracked and bleeding, dried out from the oxygen that flowed into his nose from a tube.

Days later, on Saturday, March 28, a doctor notified Lori they were taking Ken out of ICU and placing him in a regular room.

“Things,” Lori remembers, “went downhill rapidly after that.”

Lori called the hospital, desperate for updates. She knew one of the doctors caring for her husband. The doctor used to check out books with her children from the Augusta library. Lori begged the doctor to keep her informed.

The doctor called Lori at midnight.

“Ken’s having difficulty breathing,” she said. “You need to come in.”

It was sad and surreal. I had not been able to be by his side for nine days. It was heart-wrenching and so difficult. But at least it felt right that I could be back by his side.”

— Lori Clark, Ken’s wife

Lori and her three children raced to the hospital. Due to restrictions, Ken’s daughters and son were not allowed in MaineGeneral.

Lori suited up with a mask, gown and gloves before entering his room. She cried as she saw her husband, who was calm, conscious and coherent, despite his low oxygen levels and organ failure.

Lori held Ken’s hand and told him she loved him.

“It was sad and surreal. I had not been able to be by his side for nine days. It was heart-wrenching and so difficult. But at least it felt right that I could be back by his side.”

Lori pleaded with the nurses to let her kids say goodbye to their dad. The nurses apologized and explained they could not allow anyone else into the room.

Lori FaceTimed her children, who sobbed in the parking lot. One by one they shared virtual messages, telling their dad they loved him.

As his condition deteriorated, nurses gave Ken more drugs to ease his transition. He slipped into semi-consciousness, then became unconscious.

At 11 a.m. on Monday, March 30, Ken Clark took his last breath with his wife of 32 years by his side.

Heartbroken and exhausted, Lori returned home to be with her children. Over the next few days, she struggled to write her husband’s obituary:

Kenneth Jesse Clark, 68, loving and devoted husband, father, friend, and community member, died of complications from cancer and COVID-19 at MaineGeneral Medical Center on March 30, 2020 with his loving wife, Lori by his side.

For the past 18 months, Ken fought courageously against a devastating diagnosis, stage IV pancreatic cancer, which could have meant immediate surrender.

But Ken took another, harder route, finding unimaginable reserves of strength and determination during the course of a disease known for its brutality. He endured the pain and indignities of cancer and its treatment, all for the chance to enjoy more moments with family and friends…

Ken’s courage and will to survive is his legacy. The way he met the last challenges of his life will forever be an inspiration.

As Ken wished, Lori had his remains cremated. Due to COVID restrictions, she and her children, like many other families, must postpone a service or celebration of Ken’s life.

In the weeks following his death, Lori, her daughters and her son comforted each other in isolation, following Maine’s shelter-in-place orders.

Inside their home, there were memories of Ken everywhere. A stack of sympathy cards from friends and relatives. Pictures of family vacations. Plans he had started for a kitchen renovation. His shirts and coats in the closet.

During warm spring days, Lori finds solace digging in her garden. Sunday, May 10, will be an especially difficult day. Besides being Mother’s Day, it is Ken’s birthday. He would have been 69. He also would have crossed a second skydiving jump off his bucket list.

“It will be an emotional, bittersweet day for me, Sean, Emily and Elise,” Lori explained. “I know they want to strike a balance between remembering, grieving Ken and making the day special for me … It will be hard, but whatever happens it will be OK.”