Editor’s Note: The following story first appeared in The Maine Monitor’s free environmental newsletter, Climate Monitor, that is delivered to inboxes for free every Friday morning. Sign up for the free newsletter to get more important environmental news from reporter Kate Cough by registering here.

It’s not exactly easy to follow the thread of funding for the cleanup of the Callahan Mine Superfund site in Brooksville. There are a LOT of documents, for one, and very few of them seem to contain actual costs. Most of the figures I could track down came from various news outlets, which have reported final cost estimates of $23 million, then $45 million, and now $21 million to “accelerate work” at the site, which the Environmental Protection Agency says is to address a funding backlog. In an email, Dave Deegan, the EPA’s community involvement coordinator for the site, said that $28 million has been spent on cleanup to date.

Whatever the final cost winds up being, it’s safe to say it will be a lot, possibly double the initial estimates. Given that we’re approaching 20 years since the former mine was designated a Superfund site (the EPA is set to hold its annual meeting updating the public on the cleanup on Monday), I thought it might be worthwhile to provide a refresher on what’s been done so far, what it’s cost and plans for the future.

Goose Pond near Brooksville, the site of the former mine, is not the first place one would think to go looking for copper and zinc. Situated on the northwest edge of Cape Rosier, the pond is a tidal estuary that drains into Penobscot Bay. When the Callahan Mine was in operation, from 1968 to 1972, it was the only known intertidal mine in the world, according to the EPA.

People had been digging for base metals in the area adjacent to the pond since the 1880s. But it wasn’t until the 1960s, when it was acquired by the Callahan Mining Corporation, that developers got permission from the state to temporarily drain the pond and go looking for copper and zinc below its surface.

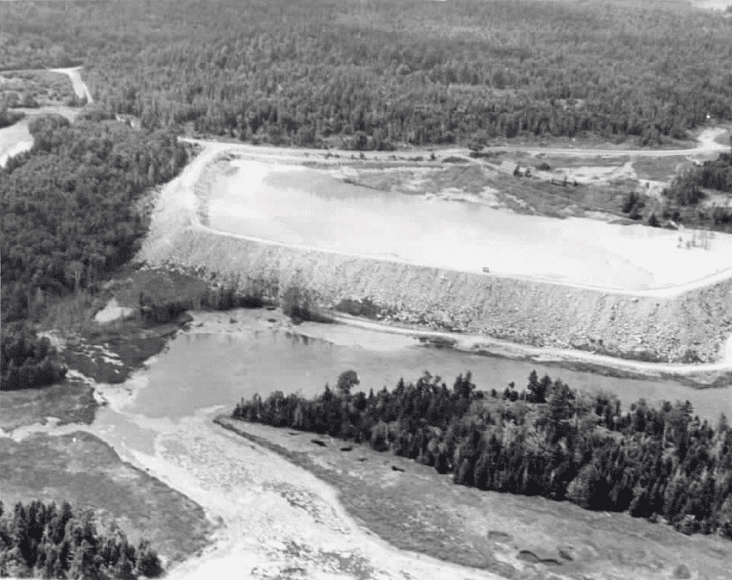

Between 1965 and 1968, Callahan constructed two dams, drained the water, and dug down hundreds of feet, extracting copper and zinc concentrates from the rock and sending them to smelters in Pennsylvania and Quebec, according to this excellent history of mining in Maine by Carolyn Lepage.

The state of Maine retained ownership of the bottom of the pond, leasing it to Callahan and collecting $25,000 in royalties during the four years the mine was in operation, according to The Ellsworth American.

Waste from the mine, known as tailings, was disposed of in a pile next to a salt marsh and creek. The tailings pond had a retaining wall lined with plastic but no bottom liner (unthinkable under modern mining regulations), allowing heavy metals to dissolve into the soil. Nearby waste rock piles and ore processing areas had no protective linings underneath them or capping on top, and the creek near the tailings pond meandered into Holbrook Island Sanctuary, a 1,230-acre undeveloped area of woods, ponds, salt marshes, volcanic rocks and sandy beaches that became a state park in 1971.

Four years and 5 million tons of waste rock later (800,00 tons of that rock was considered valuable ore), Callahan had extracted all it could from the area. It breached the dams and let the water back into Goose Pond, flooding the former mine site.

Even before the mine had closed, a group of Brooksville residents, along with representatives from the state and the mining company, formed the Goose Pond

Reclamation Society, with the aim of figuring out what to do with the property. Callahan gave the group $1,000 for its efforts, according to reports in the Bangor Daily News in 1979. The company also attempted to revegetate the waste rock piles and tailings impoundment, with little success.

In a surprising twist, Callahan decided to lease the former mine site to Maine Sea Farms, which, under the direction of fledgling marine biologist Robert Mant, piloted a project raising oyster and salmon in the temperate waters.

Callahan hired Mant and, along with a couple of investors, lent close to $500,000 in startup funds for what was one of the first aquaculture ventures in the state (known at the time as “mariculture,” which to me more evokes “marriage culture,” so I for one am glad that didn’t persist).

The experiment become, for a time, the largest pen salmon operation on the eastern seaboard, handling millions of fish, according to testimony Bob’s wife Linda gave to Congress in 1977. In 1974, Callahan sold the site to Maine Sea Farms for $25,000, but the company struggled financially and eventually suspended operations.

In the midst of all of this, Maine passed a law in 1969 requiring mining companies to post bond and submit a comprehensive site rehabilitation plan before beginning mining operations. But the Callahan site was considered grandfathered and thus not required to submit any reclamation money to the state.

Over the next two decades, not much appears in the record about activity at the former mine. In 1987, the 150-acre land portion was acquired by the Smith Cove Protection Association (now known as Smith Cove Preservation Trust), a nonprofit registered in Ohio.

Various inspections were conducted in the 1990s, but it wasn’t until 2002, 30 years after the last ore was extracted, the EPA accepted Callahan onto its National Priorities List, better known as Superfund sites. Maine has 16 such sites.

The Superfund program was established by Congress in 1980. Initially funded by taxes on petroleum and chemical companies, along with environmental income taxes, the goal of the program was to create a dedicated fund for cleaning up hazardous waste, even when a responsible party couldn’t be identified.

In 1995, Congress chose not to renew those taxes, leaving taxpayers on the hook for much of the cleanup. The program has been chronically underfunded ever since, and the number of Superfund sites getting cleaned up around the country decreased from 20 in 2009 to eight in 2014.

Congress did reauthorize a tax on chemical manufacturers in 2021 that could boost funding for the not-so-super-funded-Superfund program. Lawmakers also approved an allocation of $3.5 billion in emergency appropriations from the general fund, $21 million of which is headed to the former Callahan Mine.

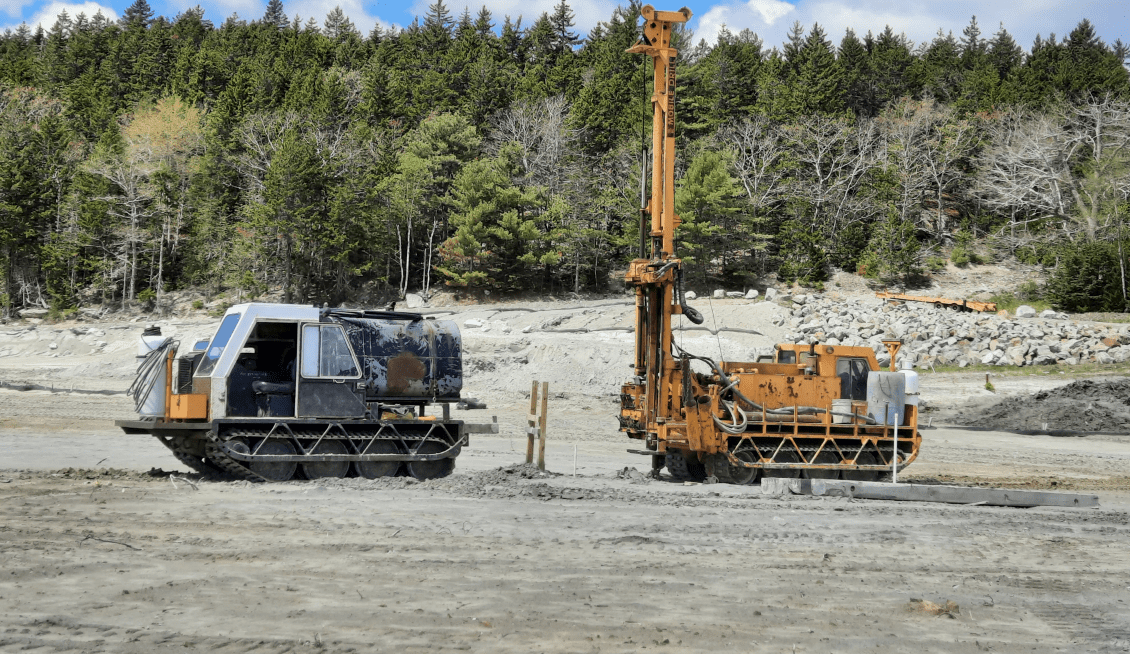

Cleanup work began in Brooksville in 2011, after years of studies and the approval of a multiphase plan. Contaminated rock and soil was consolidated, and a new system was designed and constructed to manage the tailings, including stabilization and installation of a cover, to help prevent heavy metals from leaching out when it rains. Drainage systems were installed and erosion controls put in place. The EPA has also cleaned up nearby residential properties and removed soil contaminated with PCBs.

Work at the site is ongoing, with no firm timeline for when it will be finished, although the Deegan said the Agency expects it to continue through 2024.

The Callahan Mine serves as cautionary tale, and was often invoked during hearings on the state’s 2017 mining law, which is considered one of the strictest in the country, with stringent water quality standards and a prohibition on open pit mines of more than 3 acres. It’s worth pointing out that mining regulations today are wildly different from what they were 60 years ago — the Callahan Mine would never have been permitted under today’s rules.

But it is a reminder that the alteration of our landscapes, whether it’s filling in marshland for housing developments or digging a big hole for metals so we can have cars and phones and computers, does have consequences that we will one day have to deal with. As University of Maine Geologist Martin Yates put it to me last fall: “Once you’ve opened a hole like that, it’s not really going to grow back.”

To read the full edition of this newsletter, see Climate Monitor: Twenty years in, the Callahan Mine cleanup drags on.

Kate Cough covers climate change and the environment for The Maine Monitor. Reach her by email with ideas for other stories at gro.r1770931131otino1770931131menia1770931131meht@1770931131etak1770931131.