The state will establish two new public defender offices covering Aroostook, Piscataquis and Penobscot counties, and change the name of the Maine Commission on Indigent Legal Services to the Maine Commission on Public Defense Services.

Gov. Janet Mills signed the emergency bill, L.D. 653, into law Thursday after it passed unanimously in both houses. The legislation creates positions for 10 new public defenders and 12 other staff members, bringing the total number of public defenders in Maine to 25.

“This legislation creates new public defender positions across communities in rural Maine and advances my commitment to improving the delivery of legal services to low-income people to ensure their constitutional right to counsel,” Mills said in a statement.

The state’s first public defender office opened in Augusta late last year; it covers Kennebec County and will expand to include Somerset County when staffing levels increase. It followed the establishment of a Rural Defender Unit that has five trial attorneys who travel around the state.

The commission hopes to open four more offices in the next two years. One would cover Hancock and Washington counties; one covering Androscoggin, Franklin and Oxford counties; one covering Sagadahoc, Lincoln, Knox and Waldo counties; and one covering Cumberland and York counties.

The public defender offices have been designed to handle about 30 percent of adult criminal cases in a given region, employing somewhere between three and eight attorneys with support staff. Their work will be supplemented by private lawyers in a hybrid system.

Until recently, Maine was the only state with no public defenders, instead appointing private lawyers overseen by the Maine Commission on Indigent Legal Services to represent poor defendants.

A nine-month investigation by The Maine Monitor and ProPublica published in October 2020 found that the commission repeatedly hired attorneys with criminal backgrounds, including a registered sex offender who was convicted of possessing child pornography, and a lawyer who exposed himself to a client.

The investigation found that the commission did not have enough money or staff to supervise these lawyers, many of whom had been disciplined for professional misconduct.

The ACLU of Maine sued the state in 2022 on behalf of poor defendants, claiming that the commission was failing to provide them with adequate counsel and thus violating their constitutional rights.

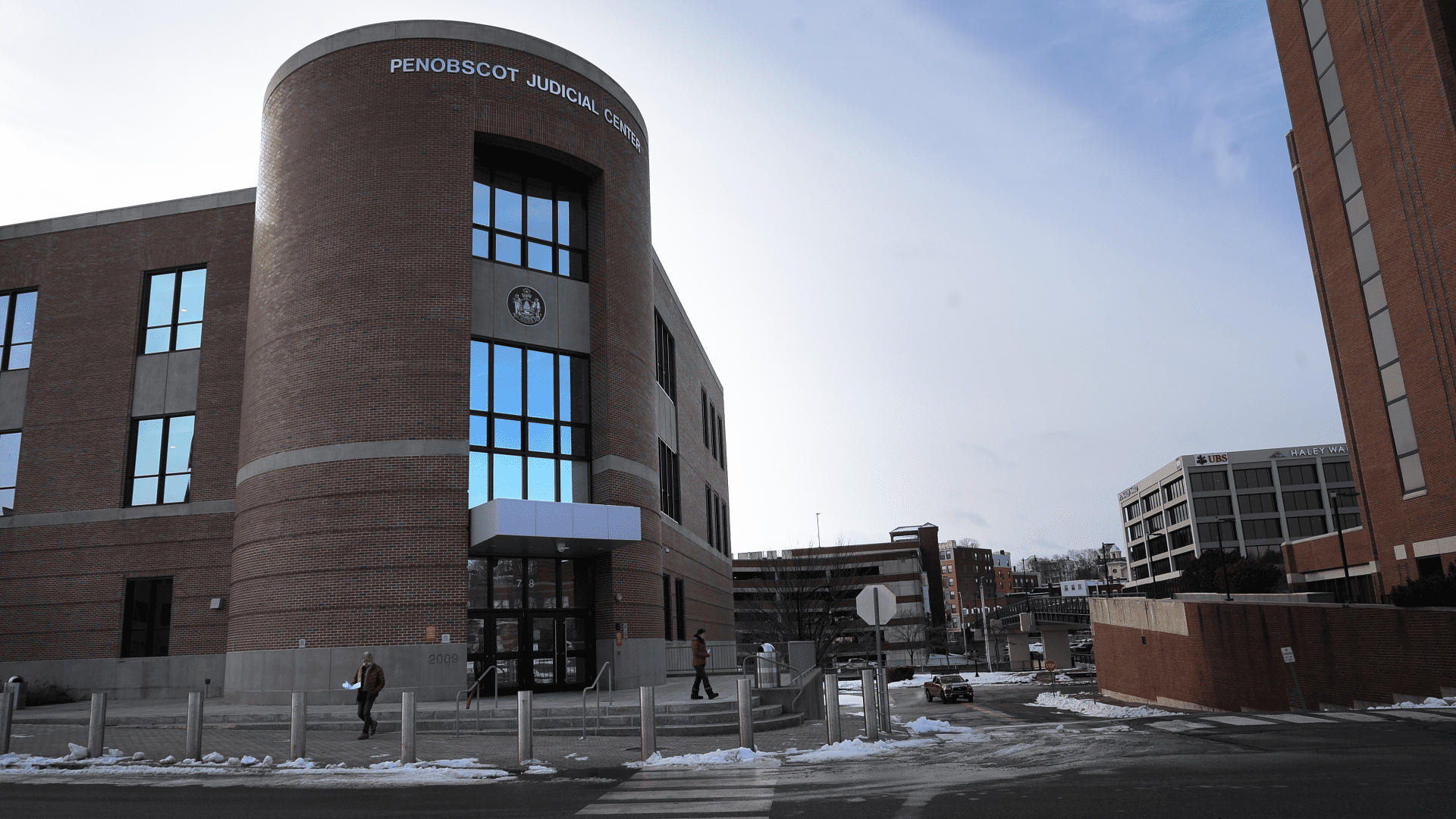

The case is ongoing, and two attempts by the parties to resolve the matter have been dismissed by a judge. Last month, Superior Court Justice Michaela Murphy rejected the second proposed settlement agreement, saying it failed to address the constitutional crisis of individuals going without legal representation.

Maine is facing a critical shortage of defense lawyers who will accept new indigent cases, and there are hundreds of people awaiting court-appointed counsel across the state, many of whom are in jail.

“Standards and accountability mean very little when very few attorneys, or no attorneys at all, have been made available by (the commission) for judges and justices to appoint,” Murphy said when she denied the settlement.

She scheduled a trial to begin in late June.

In a State of the Judiciary address to lawmakers last month, Maine Supreme Judicial Court Chief Justice Valerie Stanfill said the courts have made progress in shrinking the pandemic-induced backlog of cases, but not enough, pointing to the lack of available lawyers on the commission’s roster.

“We have people sitting in jail every day — frequently a dozen or more in Aroostook County alone — without an attorney because there is no one to take their cases,” she said. “I hope that adding some public defenders will help, but it will be a while before we really see results. And in the meantime, I fear the system will indeed collapse.”