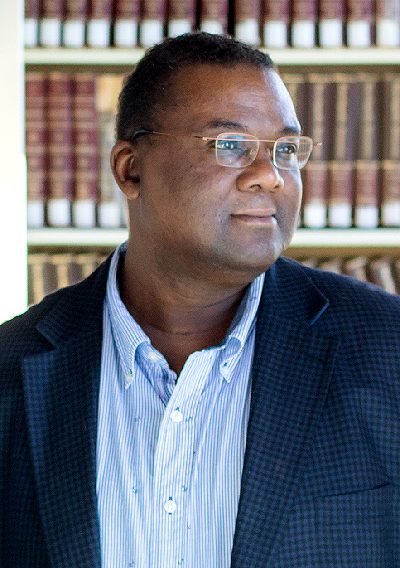

When Myron Beasley moved to Maine 11 years ago to take a position teaching African American studies and American cultural studies at Bates College in Lewiston, he was determined to reach beyond the borders of the Bates campus to make connections with people in his new community.

As someone who has lived in and traveled to many places across the globe — Myron grew up in Israel, was schooled in Europe and the United States, and has done ethnographic field work in Haiti, Brazil, Morocco, and the United States, including here in Maine — he knows how to create community wherever he is.

Dinner parties are his go-to community-builder.

Dinner parties are his go-to community-builder.

“I love having dinner parties!” he says. “Sitting with someone and looking them in the eye and no cell phones and engaging around food – that’s really, really important to me.”

To get to know his Lewiston neighbors, he held seven dinner parties on Friday nights. He invited people he already knew and they had to invite two or three people they knew but he didn’t.

“These efforts take a while, and trust takes a while sometimes, right?” he says. But the power of food to nurture relationships was something impressed on him from a young age.

His great-aunt Francis in Israel always had something cooking in her home and would insist visitors take something yummy home with them, he remembers. “What was beautiful about it — it was about love, and it was about comfort, and it was about having people come over. And that was her way of loving them,” he says.

And it has become Myron’s way, too. “If there’s food, it’s amazing what can happen around that space. I mean, even with strangers, you know?”

Q&A

Who meets your definition of trust, and how do they meet it?

Beasley: All of my good friends, of course. But also, when I think of my professional career and my colleagues — there’s a trust there, too, on a couple of different levels. Firstly, we’re all dedicated to teaching our students — not just looking at them as students, but as human — and being sincerely concerned about how we can nurture them outside the classroom, because education is not just about the intellect.

And then we also support each other. The competition in academia is generally known as being horrid, but we support each other in lots of ways — being basically respectful of each other and also finding ways to share each other’s research. You have to carve out those spaces to make that happen. And you have to work to make it happen.

Who doesn’t meet your definition? What breaks trust for you?

Beasley: People who cannot respect others and cannot respect the rules and boundaries that we as a society have placed. So, think about what’s happening politically now. We’re seeing the fragility of our democracy because so much of it is placed on this thing we call trust. We put trust in the office of the presidency, the Senate. There’s an expectation that the people who step into those positions will adhere to the traditions — even though they may not be written down — of those roles. When people in such positions treat people with a lack of respect, they break those unspoken rules and trust is broken.

Can broken trust be healed?

Beasley: Oh gosh. It’s hard. It’s challenging. It takes time. Healing broken trust is not something that happens immediately. When I think of that question, I think of the lack of genuine reflexivity in our society right now. The ability to admit that you’re wrong, but more than that, that you understand why. You hear often in our society today this phrase I despise: ‘If I offended you.’ What happened to ‘I am wrong, and this is why I failed, and I’m so sorry.’? But to preface an apology with ‘If I offended you’ is not an apology. I do believe that a clear recognition in one’s failure and admittance of why, and that they understand why they were wrong, is the beginning to repairing trust.

Has your definition of trust changed over the years? And if so, how?

Beasley: I think so, because as we grow and develop throughout life, our understanding of reality and our own lives changes. Of course, my definition has changed and continues to change. Even now, I will ponder and rethink my position when I am in situations where I am butted against something that is adamantly opposed to my position.

What do you think about the cultural definition of trust? Do you feel like that has changed over the course of your lifetime?

Beasley: Yeah. I think, at this moment, the domain of truth and trust has been shattered. The definition is becoming this slippery slope. We tend to trust blindly — culturally, we are taught to trust our cultural and political systems. There is blind trust of our government officials, for example, that they will do right. That our societal systems, like the justice system, will be equitable. But when you see over and over that there’s a justice system that allows for the senseless killing of black bodies, there has to be, for me, a lack of trust in that traditional cultural definition of trust.

What worries you?

Beasley: What worries me right now is the divisive rhetoric that’s happening in our political discourse. It is discombobulating. There is an atmosphere of anxiety. I worry about how far it will go.

What inspires you?

Beasley: What inspires me are my good relationships that I have with people, with my good friends. What inspires me are my students who ask such great questions. They help me stay excited, to be optimistic, about the world.

What issues on the state or local or national or international level do you think are really important?

Beasley: Healthcare. I think everyone should have access to it, but they don’t. I’m concerned about our public school systems. They are not supported as they should be. There are so many barriers — economic or otherwise — to having access to education and healthcare. I travel a lot so I also think international diplomacy is important. We have an abrupt and brusque — almost rude — disposition at the moment on the international stage, and I think it harms us more than it helps us.

Get to know Myron M. Beasley

Age: 48

Hometown: Hallowell and Portland

Religious affiliation: Jewish

Political affiliation: Democratic Socialist

How he describes himself: Someone who’s sincere, passionate about equality and social justice. Someone who is supportive, honest and trustworthy.

How he defines trust: Blind faith. When I engage with people, there’s a certain expectation in basic humanity. When I get in the car and drive, there’s blind faith that people will adhere to the rules of the road. That’s what I consider trust. It’s based on the view that we are inherently supportive and giving people. That people are inherently good.