Our family got an electric car two years ago and I have one major regret: I wish our previous cars could have been electric.

Recalling years spent contending with the expense, pollution, noise, mechanical issues and fluid leaks of gas-powered cars, I regret that industry and the government conspired to deprive Americans – for a quarter-century – of the vastly superior experience of electric vehicles (EVs).

Once you own an EV, you will never want a gas-powered vehicle again. Converting to electrified transportation can make one, as some quip, an EVangelist. Let me share the good news.

High performance, low maintenance, far lower impact

The EV driving experience is quiet and smooth, with none of the internal combustion engine’s stuttering shifts. This luxurious experience is true even in the cheapest EVs, like our base model Nissan Leaf (bought with federal, state and manufacturer rebates that reduced the list price by more than a third).

EVs offer instant torque, providing more power on demand than gas-driven cars. When I drove compact gas-powered cars, I could never overtake slow-moving vehicles on uphill passing lanes. Now my peppy Leaf sails by them, undeterred by steep inclines.

One of the biggest misconceptions about EVs is that they’re slow and underpowered, said Travis Ritchie, a former auto mechanic and self-described “motorsports kind of guy” who co-founded the Maine Electric Vehicle Association.

Ritchie and his wife bought two used Nissan Leafs in 2017, each for less than $13,000. He enjoys taking his car to settings “where it doesn’t belong,” like an autocross race. Performance car enthusiasts, he noted, are impressed by the electric motor’s capacity for jackrabbit starts. (So while EVs make great family vehicles, they might not be the best starter cars for teenage drivers.)

Through four years of ownership, Ritchie has had to buy only windshield washer fluid and one set of tires. No oil changes, transmission fluid, radiator hoses or exhaust systems. In his view, it’s “more of a return to simplicity.”

A 2018 data analysis found that rural residents in the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic who replaced gas-powered vehicles with electric ones could save $870 per year. And EVs produce far fewer lifetime emissions, particularly if the electricity to charge them comes from solar or wind power.

A more interactive driving experience

Our Leaf has subtly shifted my driving style by providing real-time feedback on battery use. It didn’t take long to learn that a “kindler, gentler” approach can extend the range I drive on a single charge. One auto manufacturer signals its drivers bluntly, telling them what percentage of time they spend in “economical,” “normal” and “aggressive” mode.

EV driving makes you more attuned to changes in terrain, watching as energy drains from the battery on uphill grades and returns on downslopes. Deceleration in EVs replenishes battery power through what’s known as regenerative braking.

To take full advantage of that, EVs offer one-pedal driving, in which the car starts slowing once pressure comes off the accelerator. Rare use of the brakes further reduces car maintenance. Ritchie has put 80,000 miles on his EV and it still has the original brake pads.

Vehicle range does drop in winter; EV batteries operate less efficiently in the cold and the heater draws down the battery. Fortunately, EVs on home chargers can be pre-warmed and defrosted, even by remote, without clouds of stinking exhaust. Most EVs also come with seats and steering wheels that are heated.

Range is becoming less of a concern; the median range for new EVs is now 250 miles. Even with longer trips, it takes minimal planning to locate charging locations, easily done with apps like PlugShare.

EVs have a low and well-balanced center of gravity due to the battery packs evenly distributed under their floorboards. Our Leaf handles better in snowy conditions than either of the two gas-powered compact cars I owned.

Jump-starting the transition

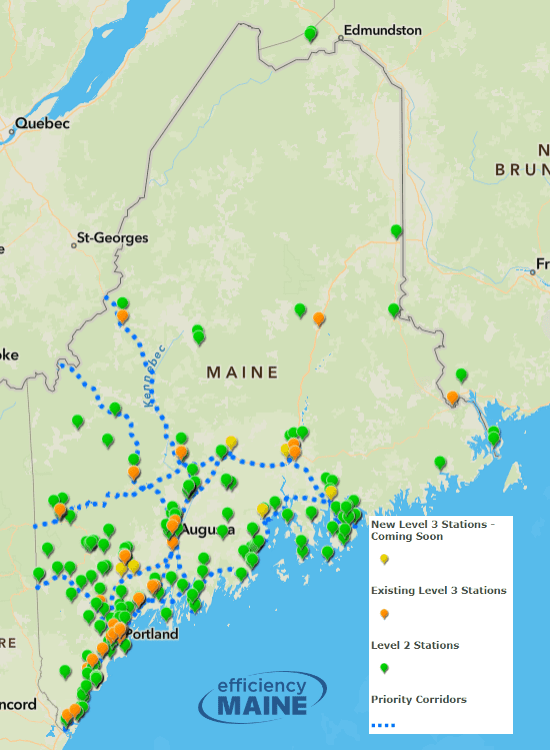

The charging infrastructure for EVs has expanded greatly: Maine now has more than 400 Level 2 chargers and 130 DC fast chargers that can provide an 80 percent charge in under 40 minutes. Efficiency Maine, which helped fund many of these chargers, is working to install additional DC fast chargers along major travel corridors, and in Aroostook and Washington counties.

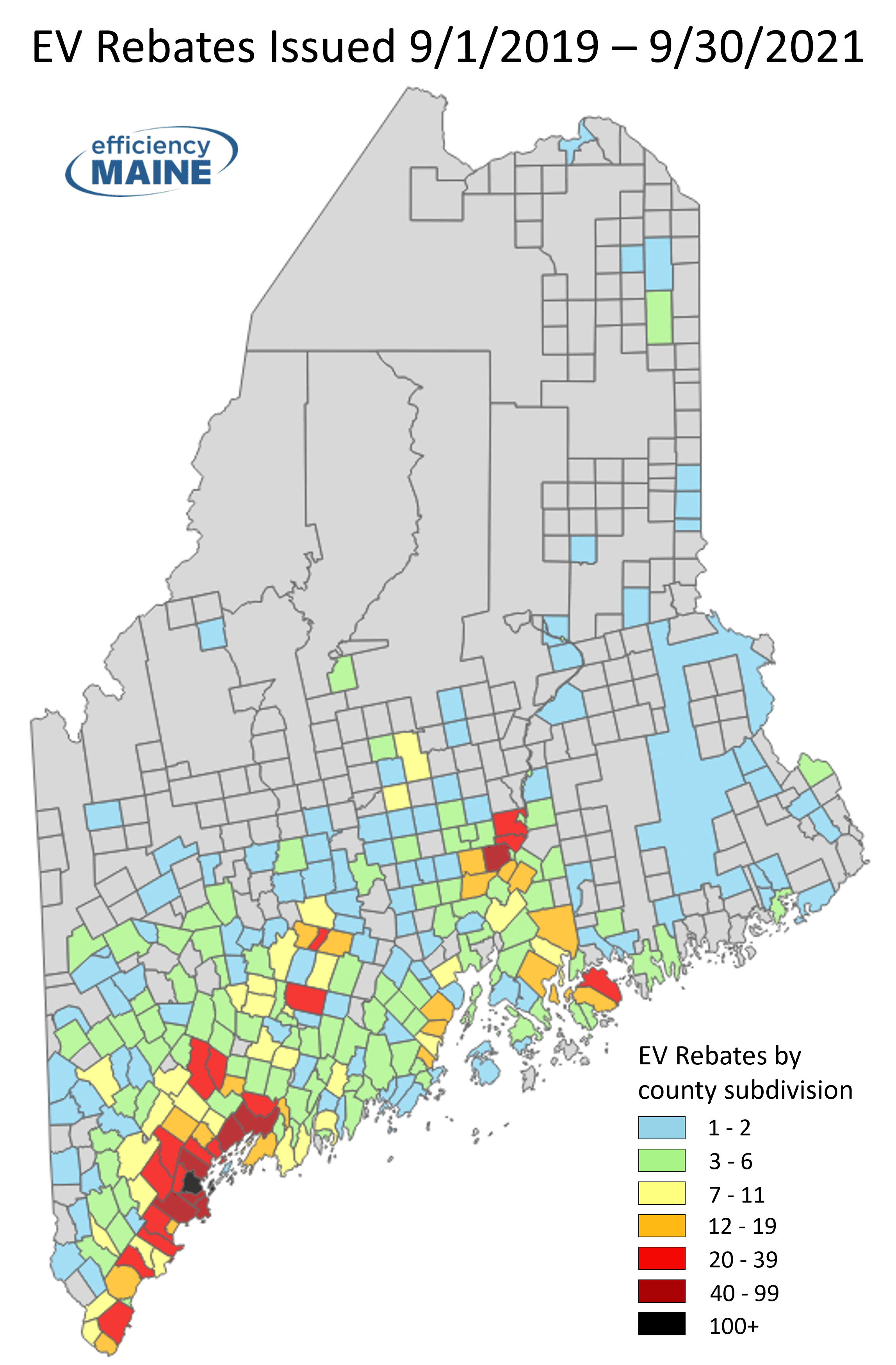

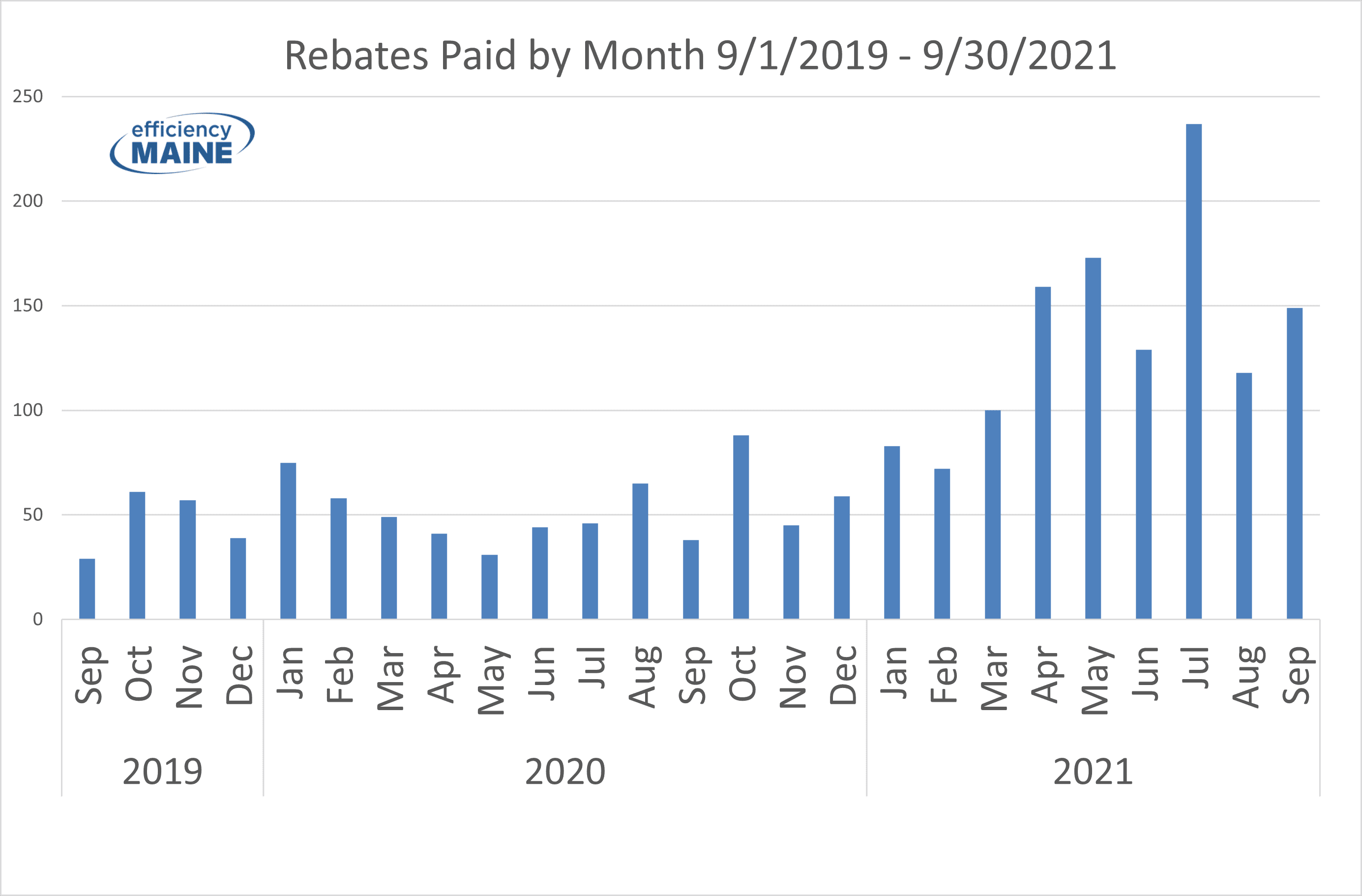

Demand for EVs is increasing with the help of state incentives (primarily between $1,000 and $2,000) that have gone to roughly 2,000 car buyers. Between 5,000 and 6,000 plug-in vehicles are registered in Maine now, a mix of all-electric ones and plug-in hybrids (PHEVs) that use electricity for the initial (typically between 25 and 40) miles.

Maine is still less than 3 percent of the way toward its target of having 219,000 EVs in use by 2030.

Many auto manufacturers have committed to transitioning their fleets to electric.

Until more new EVs are produced, the market for used EVs will remain competitive, and at least two-thirds of vehicles purchased in Maine are bought used. One-fourth of the state’s EV incentives are reserved to help low-income customers, based on fuel assistance programs, get new or used EV models. For those buyers, market prices remain a barrier, said Amalia Siegel, program manager for EV incentives at Efficiency Maine, but price parity between electric and gas-powered vehicles may come for some models within a few years.

“We’re really taking a long view,” Siegel added, with Efficiency Maine estimating that rebates for low-income drivers will be available for three to four more years. The program is also working to expand eligibility so any recipient of state benefit programs would qualify.

Barry Woods, director of EV innovation at Revision Energy, is optimistic about EV prices dropping as battery production ramps up, but acknowledged the coronavirus pandemic set back the pace of EV adoption. That setback is due to a chip shortage slowing automotive production and constraints on test-driving vehicles.

People need to drive EVs to get excited about them, Woods said. While many ride-and-drive events were canceled, some events went virtual. The Center for an Ecology-based Economy’s 2020 Solar and EV Expo, normally held in Oxford Hills, generated many informative videos and webinars for prospective buyers.

Numbers can change, fast

While fewer than 5 percent of vehicles sold annually are plug-ins, the Biden administration aims to have EVs reach 50 percent of sales by 2030, with many manufacturers setting similar goals.

That target might seem far-fetched, but consider Norway’s experience. A decade ago, EVs represented less than 1 percent of new vehicles sold annually. By 2020, EVs had 54 percent of the market share. This September, EVs topped 90 percent of Norway’s monthly vehicle sales.

In the U.S., we may finally be reaching a tipping point where the automotive world will relinquish fossil fuels with unexpected rapidity. The change can’t come fast enough. Bring on that instant torque.