They came from the townships and plantations of Concord, Lexington, Highland, Carrying Place and Pleasant Ridge. They set out for the statehouse in Augusta from the five sparsely populated backcountry communities set between the Kennebec and Carrabassett rivers, from a wooded intervale etched by streams, dappled by lakes and cradled by the hills and mountains of western Maine.

As they left, many of them passed a neatly lettered sign at the intersection of Long Falls Dam and Sandy Stream roads. The sign summed up what they were going to say to legislators later that day: “This is God’s Country. Don’t let wind towers come here and make it look like hell.”

The residents were headed to Augusta this past March 28 bearing petitions for redress. Their message had an urgency: there were two large wind power construction projects — Iberdrola Renewable’s Fletcher Mountain project and Independence Wind’s Highland Plantation project — that had been proposed for the mountains surrounding their communities.

Armed with the signatures of the majority of residents in their townships and plantations, they went to ask lawmakers to pass a bill to give them back the right to influence how the land in their communities was used.

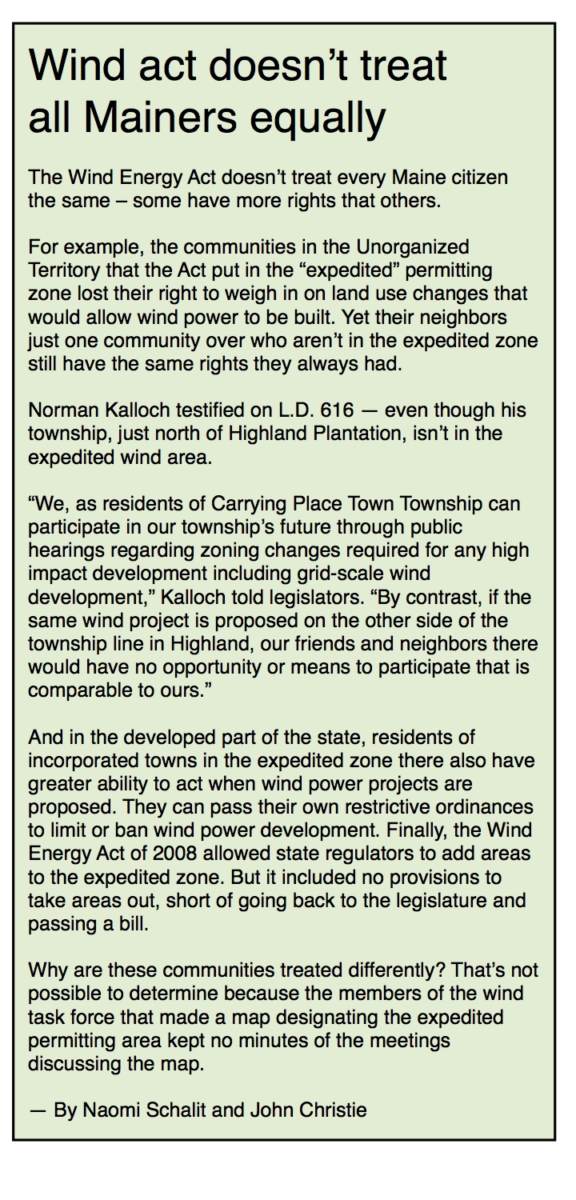

That right, they said, had been taken away from them in 2008, when Maine adopted one of the nation’s most aggressive policies to promote wind power and put their communities in a fast-track wind development zone.

As Lexington Township’s Karen Bessey Pease said, “We weren’t asked when we were put in. We have the mandate of the people in these communities to not be in it — and we’re hoping the legislature will agree.”

The bill was one of dozens of attempts over the last five years to roll back provisions of the Wind Energy Act. Almost every one of those bills had been rejected by lawmakers. But this time, there were signs that the ironclad consensus in the statehouse about the virtues of wind power was eroding.

Baldacci began it

The story begins five years ago when Gov. John Baldacci, nearing the end of his second term and eager to make Maine a national leader in wind energy, instructed a task force to devise a regulatory scheme that would streamline and speed up wind project permitting.

Baldacci’s ambitions dovetailed with the expansion agenda of the wind power representatives, the climate change agenda of the environmentalists and the economic development agenda of lawmakers on his task force, all of whom supported wind power. Task force members produced a report declaring that “Maine can become a leader in wind power development, while protecting Maine’s quality of place and natural resources, and delivering meaningful benefits to our economy, environment, and Maine people.”

The report’s recommendations were soon turned into legislation to make building wind projects easier in the state. Swiftly, unanimously and with no debate, legislators passed the Wind Energy Act of 2008.

To supporters of wind power, the legislation was a triumph.

It established “one of the most robust wind siting regimes in the nation,” said Eric Thumma, a representative of wind developer Iberdrola Renewables, a sister company to Maine’s Central Maine Power.

The Wind Energy Act set ambitious goals that could result in 1,000 to 2,000 turbines being constructed along hundreds of miles of Maine’s landscape, including the highly prized mountains where wind blows hard and consistent. The act eliminated legal obstacles that had long made wind development difficult in Maine:

• It weakened longstanding rules that required wind turbines “to fit harmoniously into the landscape.”

• It cut off a layer of appeal for those opposing state permits for wind power.

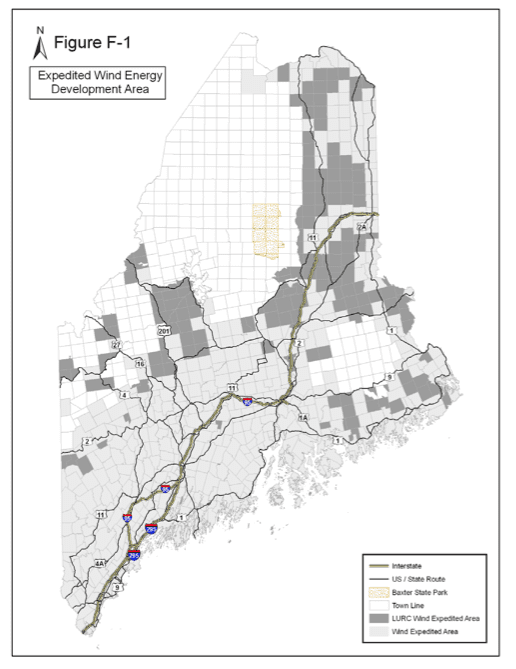

• It opened every acre of the state’s 400 municipalities to fast-track wind development, as well as one-third of the state’s Unorganized Territory.

Before the act was passed, three industrial-scale wind power projects had been built in the state; since then, seven have been approved and five of them built, with six more proposed projects under state review, according to state officials.

But to the residents of this quiet valley in western Maine, the law was no triumph. They say it took away their power to influence the future of their communities.

That’s because the law also knocked down one of the most significant obstacles to building wind towers in the rural areas of the state known as the Unorganized Territory, or UT. That obstacle was the restrictive zoning in the UT that did not allow wind turbines in the region. Under the old rules, a developer faced several steps in the Unorganized Territory to construct wind turbines. The first big hurdle was to get a rezoning.

A wind developer asking for rezoning “had certain criteria, certain hurdles that had to be met that, if you interpreted them with a straight face, you could never allow it,” said David Publicover, an Appalachian Mountain Club scientist who served on the task force.

Rezoning included formal input from citizens in the surrounding areas and beyond and could be a long and difficult process.

So in order to promote wind power development, the new law made wind turbines a “permitted use” in the approximately one-third of the UT that was designated by the task force as an “expedited permitting area.”

“One of the things (the law) did in these UT locations was, in a single stroke, make grid-scale wind energy a form of industrial development that did not require specific and appropriate zoning,” Lexington Township’s Alan Michka told legislators at the hearing. “Prior to this change, wind energy development required specific rezoning in all of the unorganized areas.”

Residents like Michka had believed that the rural character protected by that zoning was an immutable fact of life.

“We invested in our properties confident in the fact that no large industrial development would ever happen in our communities without a public discussion and a chance to be heard,” testified Maine Guide David Corrigan of Concord Township.

How the boundaries of that expedited area were set will never be known — the task force’s deliberations on the area were confidential and they kept no minutes.

Time for a second look

Almost three dozen rural residents came to the committee hearing on L.D. 616 and a number of other wind bills, and many of them spoke.

Sen. John Cleveland, D-Auburn, the co-chairman of the committee, signaled that the committee’s near-unanimous support for wind power might be changing.

“You’re talking to a brand new committee, folks who are committed to looking at your testimony, I don’t think we come precast in judgment,” Cleveland told them. “We’ll try to give you a fair hearing.”

The wind industry and its supporters were there, too.

Jeremy Payne, head of the Maine Renewable Energy Association, told the committee that they should reject the bill because it “it specifically targets two known wind development project areas: Iberdrola Renewables’ Fletcher Mountain development and Independence Wind’s Highland Plantation development. The bill proposes to remove several townships and plantations from the Expedited Permitting Area, but, notably, offers no justification for doing so.

Those two wind developers, Payne said, have invested “on the order of hundreds of thousands of dollars” in response to the Legislature’s “policy signal that these areas were designated as appropriate for wind project development.”

Ben Gilman, from the Maine State Chamber of Commerce, warned legislators that any changes would discourage investment in the state by wind power companies, which had invested “more than one billion into the Maine economy” since the Wind Energy Act was passed in 2008.

“During our recent economic downturn this has been an important part of the Maine economy,” said Gilman. “Part of the reason for this increased investment was due to the expedited permitting process put into place by the legislature.”

Committee Co-Chairman Rep. Barry Hobbins, D-Saco, said he now believes it is time to take a second look at the Act.

“It’s a healthy idea for a committee of jurisdiction to re-evaluate and take a sounding of where we are and where we need to be in the future,” said Hobbins, who voted in favor of the Wind Energy Act in 2008. He said the committee could take “a step back and looking at the whole thing,” especially, he said, because he was disinclined to take five communities out of the expedited wind area without looking at how other communities felt.

“Instead of picking and choosing, that whole issue should be re-evaluated,” said Hobbins.

An evaluation has already been done.

Lawmakers on the Energy and Utilities committee in the previous legislative session passed a bill requesting an assessment of the state’s progress in meeting the Wind Power Act’s goals and directing that legislation should be crafted from the assessment’s recommendations. The bill requested that the study “shall also consider whether places should be removed from the expedited permitting area.”

The assessment was delivered to legislators in 2012. In a section on wind project siting, the authors wrote, “The Governor, the Legislature, the Governor’s Energy Office, the Department of Environmental Protection and/or others should convene a panel to identify where in Maine expedited permitting would be allowed in a way that provides maximum energy, economic and environmental benefits and minimum harm to local residents and the environment.

“A public review process conducted by a broad cross section of individuals should be re-instituted to re-visit the topics covered by the 2008 Wind Energy Task Force that identified the expedited permitting areas and the process.”

No action has been taken by the legislature on the report’s recommendations. And the Energy and Utilities committee postponed the work session on LD 616, with no re-scheduled date announced.

Former Rep. Wright Pinkham, a Republican who lives in Lexington Township, testified in favor of LD 616 and told lawmakers he regretted his 2008 vote to pass the Wind Energy Act. Several weeks later, sitting in the dining room of Highland Plantation’s Claybrook Mountain Lodge, he reflected on legislators’ reactions the day he testified.

“Sitting there, talking with them, they absolutely agree what the ramifications are. Between shaking their heads, ‘I agree, I agree,’ and the lobbyists that are going to put huge pressure on them, I don’t know,” he said. “It depends on the pressure that’s put on them and they are going to get a lot of pressure put on them.”

And he had hope that lawmakers would see things his way.

“I don’t think anybody consciously voted to take away the rights of people in Lexington, Highland, Pleasant Ridge, Concord and all of the Unorganized Territory that’s in the expedited wind area,” he said. “They had not a clue, and that happens a lot of the time in the legislature.”